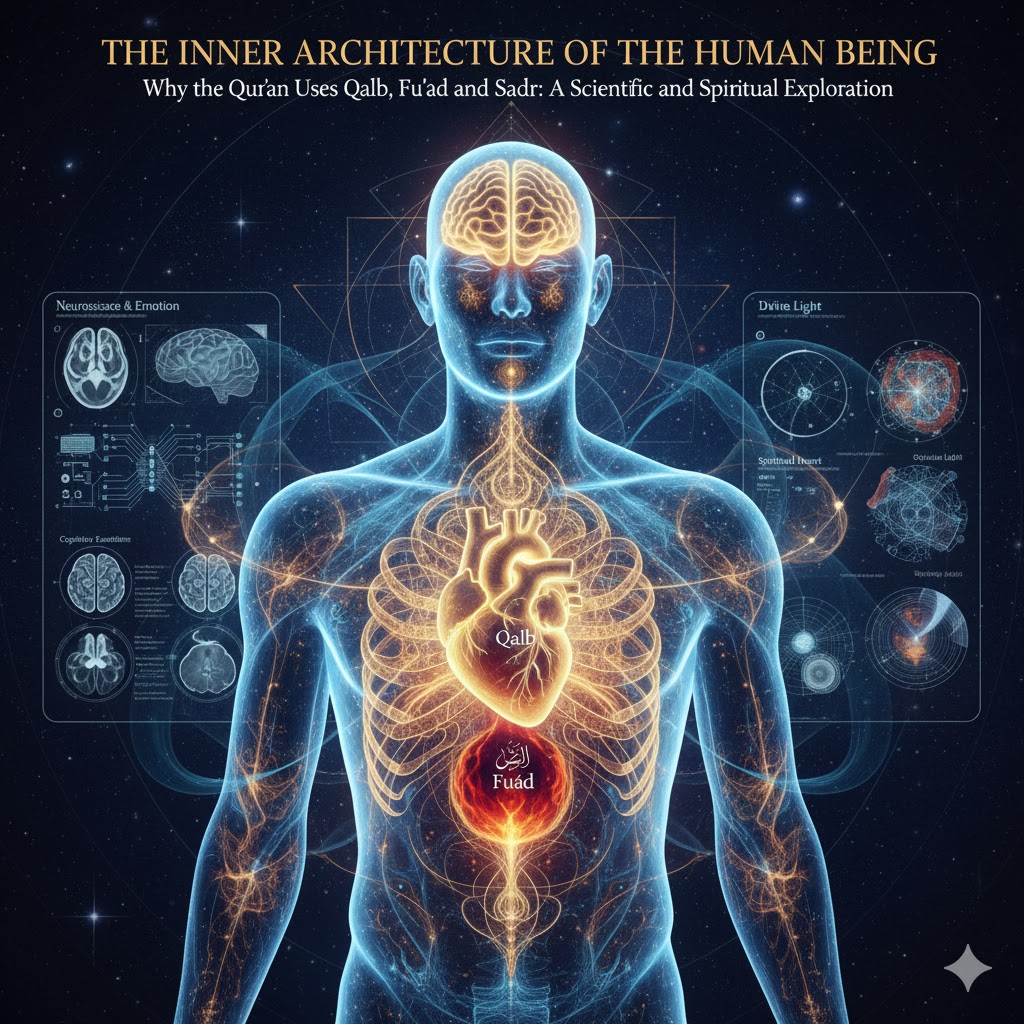

The Qur’an’s use of the terms qalb (heart), sadr (chest), and fu’ād (deep heart) has become even more striking in the modern age, where scientific inquiry increasingly acknowledges the complexity of human consciousness. These terms are not poetic metaphors; they reflect a deeply layered understanding of the human interior. The Qur’an speaks of the heart as the seat of understanding, intention, and moral clarity. It declares:

﴿لَهُمْ قُلُوبٌ لَّا يَفْقَهُونَ بِهَا﴾

“They have hearts with which they do not understand.” (7:179)

This verse is profound because it locates understanding in the heart—not the brain. The Qur’an is not speaking of biological tissue but of the inner moral-intellectual core. Modern science now affirms that the heart possesses its own complex neural network capable of influencing perception, decision-making, and emotional processing. The Qur’an uses “heart” because it speaks to a dimension of the human that is not reducible to neurons alone. Its meaning includes consciousness, moral judgment, intuition, and intention—realities that science cannot quantify.

The Qur’an also describes the psychological atmosphere surrounding the heart—the sadr. This is where anxieties, doubts, and spiritual openness manifest. When the Qur’an says:

﴿فَمَن يُرِدِ اللَّهُ أَن يَهْدِيَهُ يَشْرَحْ صَدْرَهُ لِلْإِسْلَامِ﴾

“Whomever God wills to guide, He expands his breast for Islam.” (6:125)

the expression “expand his breast” captures something psychologists today call cognitive openness or emotional spaciousness. It is the feeling of mental clarity, a reduction of internal pressure. Conversely, when the Qur’an says:

﴿وَمَن يُرِدْ أَن يُضِلَّهُ يَجْعَلْ صَدْرَهُ ضَيِّقًا حَرَجًا﴾

“And whomever He allows to go astray, He makes his breast tight and constricted.” (6:125)

it describes precisely what modern psychiatry calls anxiety, cognitive constriction, and emotional suffocation. These descriptions are astonishingly accurate for a 7th-century text, yet they go deeper than modern psychology by situating these states within a moral and spiritual framework, not merely chemical imbalances.

The Qur’an further speaks of the fu’ād, the deep heart—the seat of intense emotion, fear, longing, and intuitive awareness. When it describes the state of Moses’ mother as she cast her infant into the river, the verse reads:

﴿وَأَصْبَحَ فُؤَادُ أُمِّ مُوسَىٰ فَارِغًا﴾

“The heart of Moses’ mother became emptied.” (28:10)

The word fu’ād conveys a burning emotional core—an intensity no other Arabic word captures. It describes a psychological state so overwhelming that normal cognition temporarily collapses. Neuroscience now maps such states to deep limbic processing, where intense emotional events overpower rational thought. The Qur’an’s linguistic precision here is not symbolic—it is anatomically and psychologically accurate, capturing the layers of human experience that modern science is just beginning to model.

When the Qur’an says:

﴿إِنَّ السَّمْعَ وَالْبَصَرَ وَالْفُؤَادَ كُلُّ أُولَٰئِكَ كَانَ عَنْهُ مَسْؤُولًا﴾

“Surely, the hearing, the sight, and the heart—each of them will be questioned.” (17:36)

it elevates fu’ād to the status of a moral witness, implying that deep inner awareness—not just outward behavior—is accountable. Modern cognitive science cannot tell us why certain actions feel morally wrong or why guilt persists even when no one is watching. The Qur’an answers what science cannot: there is an inner witness embedded within us, a moral sensor that transcends neural processes.

People today expect religion to fit within the boundaries of scientific language, forgetting that science has its own limitations. Science deals with matter, not meaning; with mechanism, not morality. The Qur’an, however, addresses the whole human being—body, mind, emotion, conscience, and soul. Science describes the electrical activity of the heart, but not why the heart feels broken. It maps the limbic system, but not the origin of fear or love. It measures brain waves, but not the emergence of intuition. The Qur’an’s vocabulary—qalb, sadr, fu’ād—captures realities that science observes but cannot explain.

This is why the Qur’an remains timeless in its psychological insight. It speaks in a language broad enough to encompass biology, deep enough to describe spirituality, and precise enough to articulate emotional truth. Philosophy debates the self endlessly; psychology categorizes it; science measures it—but the Qur’an names it. And in naming it, the Qur’an reveals dimensions of existence that empirical methods cannot reach.

One of the most striking features of Qur’anic psychology is its insistence that true understanding arises not from the brain but from the qalb, the inner moral–spiritual center. The Qur’an repeatedly presents the heart as the organ of comprehension, moral awareness, and perception.

﴿أَفَلَا يَتَدَبَّرُونَ الْقُرْآنَ أَمْ عَلَىٰ قُلُوبٍ أَقْفَالُهَا﴾

“Do they not reflect upon the Qur’an? Or are there locks upon their hearts?” (47:24)

This verse shows that failure to understand is not an intellectual defect—it is a condition of the heart. A locked heart cannot perceive meaning even if the brain is perfectly functional. Modern cognitive science supports this nuance: emotional states, belief frameworks, and moral dispositions shape how people interpret information long before rational analysis occurs. The Qur’an understood this long ago—the heart determines the lens through which the mind sees.

The Qur’an uses the word sadr to describe inner space—a psychological openness or constriction that directly affects human behavior. When revelation says:

﴿فَمَن يُرِدِ اللَّهُ أَن يَهْدِيَهُ يَشْرَحْ صَدْرَهُ لِلْإِسْلَامِ﴾

“Whomever God wills to guide, He expands his chest for Islam.” (6:125)

it is describing more than spiritual receptivity: it is portraying cognitive expansion, emotional relaxation, and psychological readiness. This resonates with findings in neurology showing that positive emotional states increase neural plasticity, enabling learning, openness, and reduced anxiety. Conversely, constricted cognition appears in the verse:

﴿وَمَن يُرِدْ أَن يُضِلَّهُ يَجْعَلْ صَدْرَهُ ضَيِّقًا حَرَجًا﴾

“And whomever He allows to go astray, He makes his chest tight and constricted.” (6:125)

This is an exact linguistic mirror of the modern psychological vocabulary of anxiety, claustrophobia of thought, and emotional suffocation. The Qur’an uses a single word—sadr—to express what contemporary psychology expresses in entire diagnostic categories.

The Qur’an uses fu’ād to describe deep emotional cognition—awareness born not from reasoning but from experience, trauma, or spiritual insight. When the Qur’an narrates the emotional collapse of Moses’ mother:

﴿وَأَصْبَحَ فُؤَادُ أُمِّ مُوسَىٰ فَارِغًا﴾

“The heart of the mother of Moses became emptied.” (28:10)

the term fu’ād captures a state of shock and emotional intensity so severe that it overwhelms normal functioning. The brain does not collapse in such moments—the heart does. This aligns with neuropsychology, which shows that intense emotional experiences bypass rational processing and activate deep limbic structures linked to fear, grief, and intuition. The Qur’anic choice of fu’ād is therefore exact: it identifies the level of consciousness where emotional upheaval takes place.

Another verse strengthens this point:

﴿مَا كَذَبَ الْفُؤَادُ مَا رَأَىٰ﴾

“The heart did not deny what it saw.” (53:11)

This is extraordinary. It suggests that fu’ād can perceive truths that the rational mind cannot process, affirming a spiritual intuition beyond logical analysis. Modern research speaks of “heart-brain coherence,” where emotional alignment produces clarity unreachable by cognition alone. The Qur’an described this 1400 years ago.

The Qur’an makes the heart—not the brain—the center of accountability.

﴿إِنَّهَا لَا تَعْمَى الْأَبْصَارُ وَلَـٰكِن تَعْمَى الْقُلُوبُ الَّتِي فِي الصُّدُورِ﴾

“It is not the eyes that go blind, but the hearts within the breasts.” (22:46)

Blindness here is not medical; it is moral and existential. A person can have perfect eyesight and yet fail to see truth. This aligns with moral psychology, which identifies that ethical blindness arises from internal dispositions and emotional biases, not sensory limitations. The Qur’an locates spiritual blindness in the heart because meaning is perceived through the heart’s moral clarity, not through physical vision.

Even revelation itself addresses the heart first, not the brain.

﴿نَزَلَ بِهِ الرُّوحُ الْأَمِينُ عَلَىٰ قَلْبِكَ﴾

“The Trustworthy Spirit brought it down upon your heart.” (26:193–194)

This verse alone overturns the modern assumption that knowledge is purely intellectual. Revelation is received in the heart, not the mind. Why? Because the heart integrates understanding, emotion, moral awareness, and intention—dimensions absent from the purely rational brain. The heart is where knowledge becomes transformation.

Today’s obsession with scientific vocabulary has created the illusion that science is the highest or only form of knowledge. But the Qur’an speaks in a language that transcends the limitations of empirical description. Science can analyze neural circuits, but it cannot articulate:

- why we feel meaning,

- how we experience moral responsibility,

- what conscience is,

- how intuition emerges,

- why love, fear, and awe move the heart before the brain.

These belong to the unseen dimensions of the self—realities that the Qur’an names directly through qalb, fu’ād, and sadr. This linguistic precision is not only spiritually profound—it is psychologically and scientifically coherent.

In an age where nearly every individual seeks scientific validation for belief, it becomes crucial to understand that not every truth belongs to the domain of science. Science is a method—powerful, precise, and indispensable—but it is also inherently limited. Its tools measure quantities, not meanings; mechanisms, not motives; chemical reactions, not conscience. The great questions that shape human existence—Why are we here? What is the purpose of life? What is right and wrong? What does it mean to be conscious? What makes a human morally accountable?—do not arise from the physical layer of reality, and therefore cannot be answered by physical methodologies. Religion, morality, philosophy, consciousness, and metaphysics belong to the human sciences, disciplines that require introspection, narrative, interpretation, and revelation, not laboratory instruments or mathematical formulas. These fields describe the qualitative dimensions of life—the experiences that make us human.

This is precisely why the Qur’an’s linguistic architecture is not only spiritually profound but intellectually magnificent. It does not attempt to replace scientific language, nor does it bind itself to empirical constraints. Instead, it speaks to the entire human reality—biological, emotional, ethical, and spiritual—using words that contain layers of meaning far beyond literal anatomy. In qalb, the Qur’an unites intention, moral clarity, and spiritual perception. In fu’ād, it captures emotional intensity and deep awareness. In sadr, it describes psychological space, openness, and constriction. These are not simplifications of scientific truth; they are expansions of it—conceptual frameworks that express the richness of human experience that science has not yet, and perhaps cannot ever, fully decode. Modern neuroscience only now begins to explore the heart–brain connection, emotional cognition, and embodied intelligence, yet the Qur’an articulated these truths with astonishing brevity centuries ago. Its language remains timeless because it addresses truths that transcend empirical boundaries—truths that reside not in microscopes or data sets, but in the living human soul.

Conclusion

In the final view, the Qur’anic language of qalb, fu’ād, and sadr represents far more than ancient metaphor; it is an integrated framework for understanding the human interior—one that modern science is slowly catching up to. The Qur’an’s choice of these terms shows an extraordinary awareness of the layered human self: a moral center that decides, a deep heart that feels intensely, and a psychological space where thoughts and anxieties circulate. Neuroscience can now map emotional processing in the heart and limbic regions, psychology can describe cognitive openness and constriction, and philosophy can debate consciousness, but none of these disciplines can fully explain why the human being experiences meaning, intention, guilt, longing, or spiritual awakening. Science can measure the brain, but not the soul; philosophy can analyze thought, but not the moral pull of the heart; psychology can categorize emotion, but not the spiritual intuition captured by fu’ād.

The Qur’an’s linguistic system therefore stands as a comprehensive model that embraces the biological, psychological, moral, and spiritual dimensions simultaneously—something no scientific field or philosophical school has ever achieved. In an age obsessed with scientific validation, it is crucial to remember that not all truths are scientific truths. Science has limits, and many realities—conscience, faith, purpose, emotion, intuition, morality—belong to the human sciences and to revelation. By expressing profound inner realities in a vocabulary simple enough for every reader yet deep enough to engage scholars and neuroscientists alike, the Qur’an demonstrates a timeless mastery of human psychology. It speaks to the whole human being—not merely the body or the brain, but the heart in all its layers. And it is in this totality that the Qur’an reveals its unmatched ability to describe who we are, how we feel, how we choose, and how we seek meaning in a world that science alone cannot explain.