Introduction: The Illusion of Ideological Wars

For centuries, wars have been explained to ordinary people through the language of ideology. Governments claim they fight to defend freedom, spread democracy, protect national honor, preserve religious values, or uphold human rights. These narratives are repeated in political speeches, school textbooks, news broadcasts, and popular culture until they become accepted truths. To question them is often portrayed as unpatriotic or morally suspect. Yet when these narratives are examined through the lens of political reality rather than emotional appeal, a different and far more uncomfortable picture emerges.

History shows that ideology is rarely the true cause of war. Instead, ideology functions as a carefully constructed justification—designed to mobilize populations, silence opposition, and legitimize violence. Behind the moral language lies a hard structure of economic interests, strategic calculations, and power politics. Wars do not begin simply because values are threatened; they begin when powerful actors believe their interests can be advanced, protected, or expanded through force.

This gap between public explanation and political reality is not accidental. Modern states require mass participation to wage war—soldiers, taxpayers, and social consent. Ideological narratives transform complex geopolitical struggles into simple moral binaries of good versus evil, allowing governments to secure public approval while avoiding scrutiny of the real motivations behind conflict. In this process, ideology becomes a tool of governance rather than a guiding principle of action.

The contradiction becomes even clearer when observing how the same powers apply their stated values selectively. Human rights violations are condemned in rival states but ignored in allied ones. Democracy is promoted where it aligns with strategic goals and abandoned where it threatens existing interests. Such inconsistencies reveal that principles are negotiable, but interests are not.

Understanding war through this framework is essential in the modern world, where conflicts are no longer isolated battles between armies but interconnected struggles shaped by global markets, energy resources, military industries, and geopolitical alliances. Without recognizing the central role of interests, public discourse remains trapped in surface-level debates that obscure responsibility and prevent meaningful accountability.

This analysis begins from a simple but critical premise: wars are not fought for ideologies; they are fought for interests. By unpacking how ideology is used, who benefits from war, and why conflicts persist despite enormous human costs, this article aims to move beyond slogans and reveal the deeper political logic that governs modern warfare.

in english

Ideology as a Political Tool, Not a Cause

Ideology occupies a central place in how wars are explained, justified, and remembered—but rarely in why they actually begin. In political practice, ideology functions less as a motivating force and more as a strategic instrument used by states to manufacture legitimacy. It provides wars with moral language, emotional weight, and social acceptability, while concealing the material and strategic interests that truly drive decision-making at the highest levels of power.

Modern states cannot wage large-scale wars through coercion alone. They require public consent, sustained over time, often in the face of rising casualties, economic hardship, and social disruption. Ideology fills this gap. By framing war as a moral necessity—rather than a political choice—governments transform complex power struggles into ethical imperatives. Citizens are not merely asked to support a policy; they are asked to defend a value, an identity, or a way of life.

This is why ideological framing tends to simplify reality into binary oppositions: freedom versus tyranny, civilization versus barbarism, faith versus evil, democracy versus authoritarianism. Such binaries leave little room for nuance or critical inquiry. Once a conflict is moralized, opposing it becomes socially risky. Dissent is no longer interpreted as disagreement but as betrayal, weakness, or even treason. In this environment, ideology does not enlighten the public—it disciplines it.

Crucially, ideology is not applied consistently. States that loudly champion democracy may simultaneously support authoritarian regimes when strategic interests demand it. Governments that claim to defend human rights may overlook mass violations committed by allies while exaggerating or instrumentalizing abuses committed by rivals. This selective application exposes the instrumental nature of ideology. If principles were truly guiding policy, they would be applied universally. Instead, they are activated or suspended depending on geopolitical convenience.

Another important function of ideology is its ability to depersonalize responsibility. When wars are framed as historical necessities or moral obligations, individual decision-makers fade into the background. War appears inevitable, almost natural, rather than the result of deliberate choices made by political elites. This diffusion of responsibility protects those in power from accountability while shifting the burden of sacrifice onto ordinary citizens.

Ideology also plays a psychological role in sustaining wars once they have begun. As conflicts drag on and original justifications collapse—when promised victories fail to materialize or evidence contradicts official claims—ideological narratives are adjusted rather than abandoned. New moral goals are introduced, enemies are redefined, and the meaning of “success” is reshaped. This flexibility allows wars to continue long after their original rationale has eroded.

From a political analysis perspective, the key insight is this: ideology follows power; it does not lead it. Ideological language is selected, modified, and deployed to align public perception with elite interests. It is not the engine of war, but the camouflage that allows war to proceed with popular acquiescence.

Recognizing ideology as a tool rather than a cause does not mean dismissing values altogether. It means understanding how values are used, who uses them, and for what purpose. Without this awareness, societies remain vulnerable to manipulation—mobilized by words while decisions are made elsewhere, driven not by ideals but by interests.

Economic Interests: The Material Foundation of War

Behind every major modern conflict lies a material question that is rarely discussed openly: who gains economically from war. While ideology provides moral cover, economic interests provide the structural incentive. States may speak the language of values, but they act according to calculations rooted in resources, markets, and long-term economic advantage. In this sense, war is not an irrational breakdown of politics—it is often politics conducted through force to secure economic outcomes.

At the center of this dynamic is control over natural resources. Energy resources such as oil and gas, strategic minerals, rare earth elements, and even water have become central to national power in the modern global economy. Access to these resources determines industrial capacity, military strength, and geopolitical leverage. When such resources are concentrated in politically weak or strategically exposed regions, conflict becomes not only possible but predictable.

A defining example is the Iraq War. Publicly justified through claims of weapons of mass destruction and the promotion of democracy, the war’s deeper economic logic was clear to many analysts from the outset. Iraq possessed one of the world’s largest proven oil reserves and occupied a critical position in the global energy market. After the invasion, while the ideological justification collapsed due to the absence of WMDs, the economic restructuring of Iraq’s oil sector proceeded rapidly, opening access to Western energy corporations and reshaping regional energy politics. The war’s moral narrative failed, but its economic objectives endured.

Economic interests also explain why wars are often fought not to achieve decisive victory, but to create controlled instability. Prolonged conflict weakens state institutions, reduces regulatory capacity, and increases dependency on external actors. In such environments, foreign corporations gain leverage, local resistance fragments, and long-term economic extraction becomes easier. Stability, from this perspective, is not always desirable—predictable instability can be more profitable.

Beyond resources, wars are closely tied to trade routes and chokepoints. Control over sea lanes, pipelines, canals, and transit corridors allows states to influence global commerce without direct ownership of resources. Conflicts in regions such as the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and parts of Africa cannot be understood without considering their role in global supply chains. When trade routes are threatened or reoriented, military force becomes a tool of economic regulation.

Another critical dimension is the arms industry. Modern warfare sustains an enormous military-industrial ecosystem involving weapons manufacturers, logistics firms, private security contractors, and reconstruction companies. War creates guaranteed demand, long-term contracts, and political influence. In this system, peace is not neutral—it is economically disruptive. The longer a conflict lasts, the more entrenched these interests become, creating structural resistance to diplomatic resolution.

Importantly, economic motivations do not operate in isolation from the state. They are embedded within national security doctrines, foreign policy institutions, and elite networks where political power and economic capital intersect. Decisions to go to war are rarely made solely by politicians acting independently; they emerge from environments where economic stakeholders, strategic planners, and political elites share overlapping interests.

For the general public, these economic dimensions remain largely invisible. Resource contracts, defense budgets, and corporate lobbying occur far from public scrutiny, while ideological narratives dominate public discourse. This separation ensures that citizens debate moral abstractions while wars are shaped by material calculations.

Understanding war through its economic foundations does not imply crude determinism or conspiracy. Rather, it highlights a structural reality: wars persist because they are economically functional for powerful actors, even when they are socially catastrophic for populations. Until this imbalance is confronted, wars will continue to be explained in moral terms while driven by material interests.

In the next section, the analysis moves beyond economics to examine how geopolitical strategy and power balance transform economic interests into military action, shaping conflicts that extend far beyond the battlefield.

Geopolitical Strategy and the Logic of Power

While economic interests provide the material foundation of wars, geopolitics provides their strategic logic. Wars are not only fought to gain resources, but to shape the global balance of power—to decide who dominates, who influences, and who obeys. In international politics, power is never static. Rising powers challenge existing ones, dominant states attempt to preserve their position, and weaker states become arenas where these struggles unfold.

At its core, geopolitics is about space, influence, and security. States seek to control or influence regions that are strategically valuable due to their geography, proximity to rivals, or role in global systems. These regions often include borderlands, transit zones, buffer states, and maritime chokepoints. When diplomacy fails to secure these interests, military force becomes an extension of geopolitical competition.

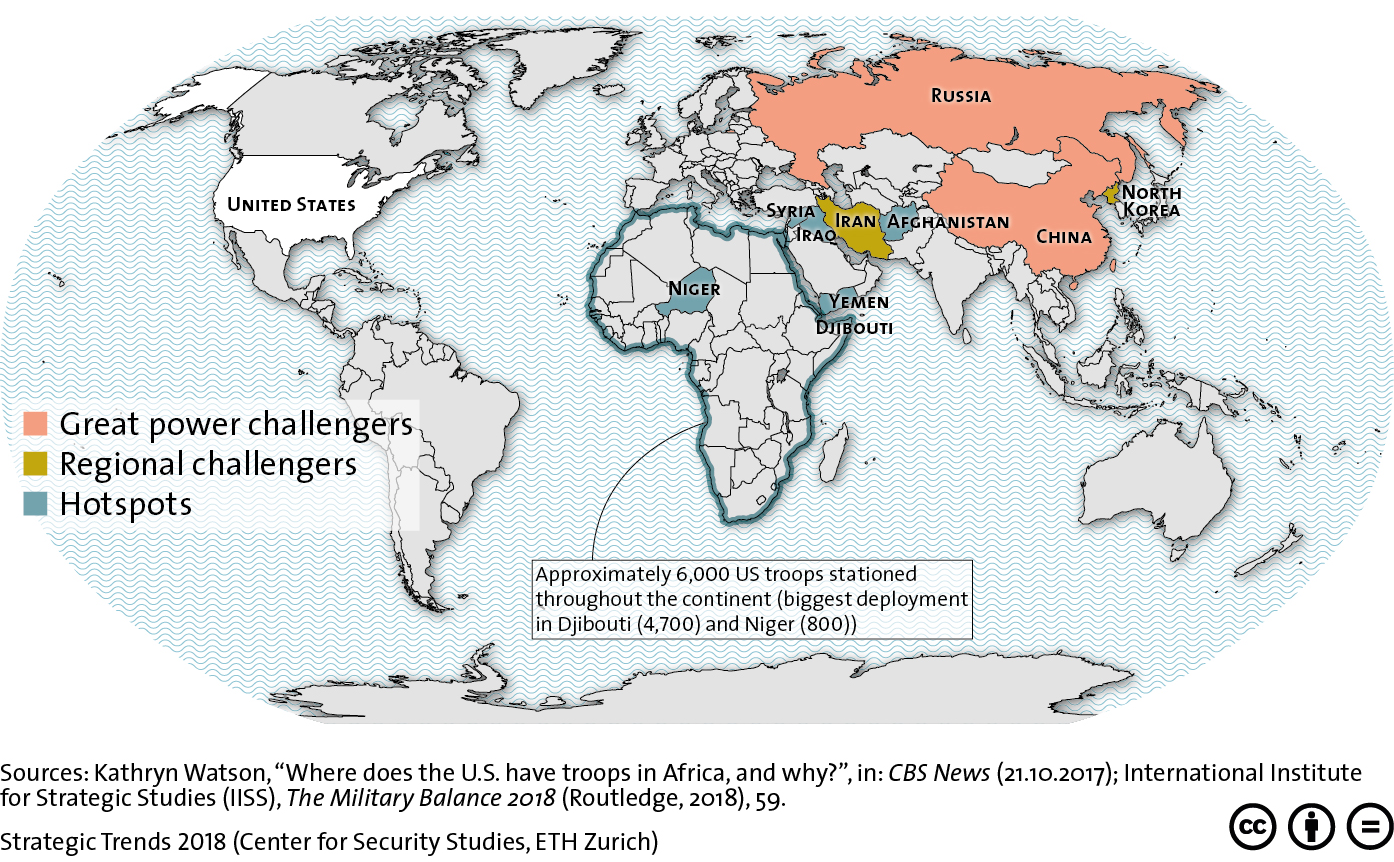

A central concept in geopolitical thinking is strategic containment—the effort by powerful states to prevent rivals from expanding their influence. This logic has shaped global politics since the Cold War and continues to define contemporary conflicts. Alliances, military bases, economic pressure, and proxy wars are all tools used to maintain favorable power balances without direct confrontation between major powers.

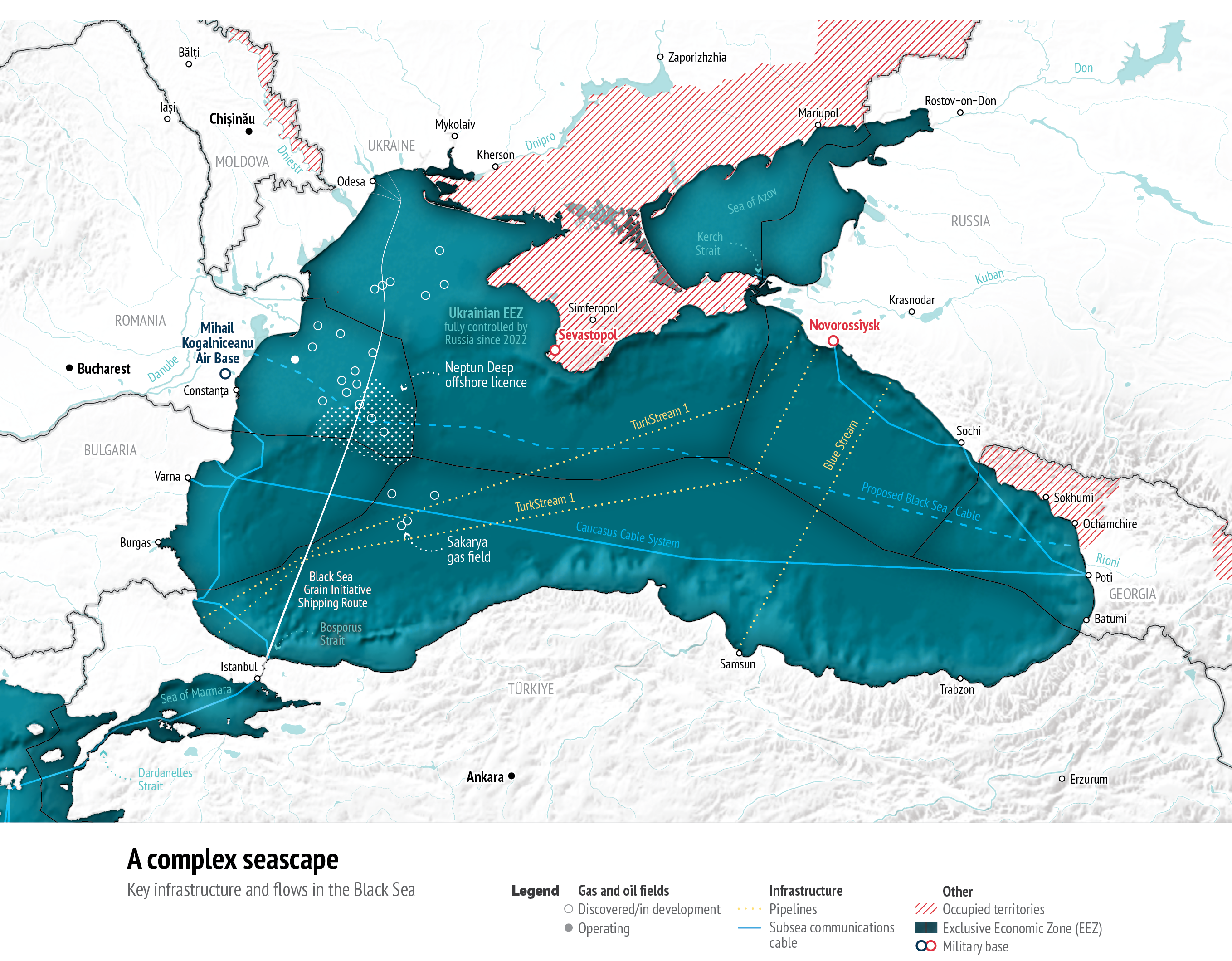

The Russia-Ukraine War exemplifies this dynamic. Public discourse largely frames the conflict as a struggle between democracy and authoritarianism, or as a defense of Ukrainian sovereignty. While these elements exist, they do not fully explain the war’s intensity or persistence. From a geopolitical perspective, the conflict is deeply tied to:

- The eastward expansion of NATO

- Russia’s perception of strategic encirclement

- Control over the Black Sea region

- Energy transit routes linking Eurasia to Europe

Ukraine’s geographic position—situated between Russia and Western Europe—transforms it into a geopolitical fault line. For Russia, losing influence over Ukraine is not merely symbolic; it represents a strategic setback that alters regional power dynamics. For NATO and Western powers, integrating Ukraine into their security architecture would significantly weaken Russian strategic depth. The war, therefore, is not just about Ukraine—it is about who defines the security order of Eastern Europe.

Geopolitical wars are rarely about total conquest. Instead, they aim to:

- Limit a rival’s options

- Increase bargaining power

- Redefine regional rules

- Signal strength to allies and adversaries

This is why such conflicts often remain unresolved or frozen. A decisive victory may be less valuable than prolonged pressure that reshapes behavior over time. In many cases, instability itself becomes a strategic outcome, keeping rival powers distracted, economically strained, or diplomatically isolated.

Another important aspect of geopolitics is the use of proxy conflicts. Major powers avoid direct war with one another due to catastrophic risks, especially in the nuclear age. Instead, they compete indirectly by supporting opposing sides in regional conflicts. This allows them to advance interests while limiting direct costs. The result is that local populations suffer wars whose ultimate objectives lie far beyond their borders.

Geopolitical strategy also explains why international law is applied selectively. Actions that would be condemned if taken by weaker states are tolerated—or justified—when carried out by powerful ones. Stability, sovereignty, and human rights become flexible concepts, adjusted to align with strategic priorities. In this system, power determines legitimacy, not the other way around.

From a political analysis standpoint, geopolitics reveals why wars persist even when they appear irrational or excessively destructive. They are not driven by emotion or misunderstanding alone, but by calculated efforts to shape the international system. States may change leaders, slogans, and narratives, but their geopolitical imperatives remain remarkably consistent.

Understanding war through geopolitical logic forces a difficult realization: many conflicts are not meant to be “won” in a traditional sense. They are meant to manage power, contain rivals, and preserve dominance—even if that means endless instability for those caught in between.

The next section will examine how this geopolitical logic is sustained and normalized through media narratives, propaganda, and information control, ensuring that wars of interest continue to be perceived as wars of principle.

Media, Propaganda, and the Manufacturing of Consent

No modern war can be sustained without narrative control. Tanks, missiles, and soldiers may fight on the battlefield, but public opinion is managed on a different front altogether—the media. In contemporary politics, media does not merely report wars; it actively constructs their meaning. Through selective framing, repetition, and omission, media transforms wars of interest into wars of necessity.

The primary function of war-time media is not to inform, but to normalize conflict and secure public consent. This process begins even before the first shot is fired. Potential enemies are gradually dehumanized, threats are exaggerated, and complex geopolitical tensions are reduced to emotionally charged storylines. By the time war begins, the public has already been psychologically prepared to accept it as unavoidable.

A key technique used in this process is framing. Media outlets choose which facts to highlight and which to ignore. Civilian casualties caused by allied forces are described as “collateral damage,” while similar actions by adversaries are labeled as war crimes. Historical context is stripped away, leaving audiences with isolated events that appear spontaneous rather than structurally produced. This selective visibility ensures moral clarity where reality is morally ambiguous.

Equally important is what the media does not cover. Economic motivations, arms industry profits, corporate lobbying, and long-term strategic objectives rarely receive sustained attention. These topics are complex, less emotionally engaging, and potentially destabilizing to official narratives. Instead, coverage focuses on personalities, dramatic imagery, and moral outrage—elements that keep audiences emotionally invested but politically shallow.

Propaganda in modern democracies does not resemble the crude state messaging of the past. It is subtle, decentralized, and often outsourced to supposedly independent institutions. Experts, think tanks, retired generals, and analysts dominate media discussions, many of whom have direct or indirect ties to defense industries or state institutions. Their authority creates an illusion of neutrality while reinforcing dominant narratives. Dissenting voices are not always censored outright; they are marginalized, framed as extreme, or dismissed as unrealistic.

Digital media has intensified this dynamic. Social media platforms amplify emotionally charged content, rewarding outrage and simplification over depth. Algorithms favor narratives that align with dominant power structures, either through direct moderation or economic incentives. As a result, war-time discourse becomes polarized: users are pushed to choose sides rather than ask questions. Critical analysis is drowned out by moral absolutism.

Another crucial role of media is temporal manipulation. Wars are presented as immediate crises detached from historical causality. Audiences are encouraged to focus on the present moment—“what must be done now”—rather than on how policies, alliances, and interventions created the conditions for conflict. This short-term framing benefits decision-makers by shielding them from accountability for long-term strategic failures.

The relationship between media and political power becomes most visible when narratives suddenly shift. Wars that were once portrayed as moral imperatives quietly disappear from headlines when they become inconvenient or lose public support. The human suffering continues, but attention moves elsewhere. This selective attention reveals that media interest is not driven by humanitarian concern, but by political relevance.

From a political analysis perspective, media is not a neutral observer of war; it is a central actor. By shaping perception, it shapes consent. By defining reality, it defines legitimacy. Wars fought for interests depend on media narratives to appear as wars fought for values.

Understanding this role of media is essential for breaking the cycle of manipulation. Without narrative control, wars lose their moral cover. Without moral cover, interests become visible. And when interests are exposed, public resistance becomes possible.

The next section will examine the human cost of wars of interest—who pays the price, who benefits, and why the burden of sacrifice consistently falls on those with the least power and the least voice in the political system.

International Institutions and Selective Morality

Global institutions claim neutrality and justice, yet power dynamics dominate decision-making. The UN Security Council’s veto system ensures that major powers are rarely held accountable. Similarly, financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank often impose economic policies on war-affected states that benefit lenders more than populations.

This creates a global order where:

- Powerful states operate above the law

- Weak states become battlegrounds

- Ideology masks inequality and coercion

Media, Propaganda, and Public Consent

No war can be sustained without public support. Media plays a critical role in shaping perceptions by:

- Simplifying complex conflicts into good vs. evil

- Amplifying emotional imagery

- Marginalizing dissenting voices

By controlling the narrative, states ensure that citizens focus on ideology rather than interests. Questions about profit, power, and long-term consequences are pushed aside in favor of patriotic sentiment.

Who Pays the Price?

While interests are protected at the top, the cost of war is borne by:

- Ordinary citizens

- Soldiers from lower economic classes

- Displaced populations and refugees

Nations do not truly win wars; interests do. The human cost is treated as collateral damage in pursuit of strategic goals.

Conclusion: Understanding War Beyond the Narrative

The statement “Wars are not fought for ideologies, but for interests” is not cynicism—it is political realism. Recognizing this truth allows societies to:

- Question official narratives

- Resist emotional manipulation

- Demand accountability from power structures

As long as wars are analyzed through ideological lenses alone, their true causes will remain hidden. Only by understanding the interplay of economics, geopolitics, and power can we grasp why wars begin, why they persist, and why peace is so often postponed.

Ideology speaks to the heart, but interests govern the world.