What does it mean when the Qur’an says that every living thing is made from water?

When the Qur’an declares, “We made from water every living thing” (21:30), it is offering a statement far deeper than a biological fact. This verse appears in a passage describing the creation of the heavens and the earth, suggesting that water is not merely a liquid found on Earth but a foundational substrate woven into the fabric of life itself. In another place, the Qur’an describes the human being as emerging from a “mingled drop of fluid” (76:2), emphasizing that the earliest stage of human existence begins with water. The scripture reinforces this across species, stating that “Allah created every living creature from water” (24:45), making water the universal ingredient of life on earth. Yet the Qur’an also elevates water beyond the biological plane. When it proclaims that “His Throne was upon water” before the creation of the heavens and the earth (11:7), it portrays water as a primordial cosmic substance — the foundational medium from which the physical universe unfolded. This “first water” is not the water of oceans and rivers but a pre-material essence at the dawn of creation. Modern science, which identifies water as the universal solvent and the indispensable environment for biochemical reactions, now affirms the same truth: life cannot emerge or survive without water, and all scientific exploration for extraterrestrial life begins with the search for water. Thus, the Qur’anic statement stands simultaneously as a spiritual insight and a scientific principle — a point where revelation and empirical knowledge converge on the same elemental truth.

How can the Qur’anic idea of primordial water explain the origins of the universe?

When the Qur’an states that “His Throne was upon water” (11:7), the verse is not describing the physical waters of oceans or rivers but pointing toward a pre-material medium that existed before the structured universe. In classical Islamic scholarship, this “water” was often described as the primordial substrate — the first created substance from which all other forms, elements, and states of matter were unfolded. If the heavens and the earth were once a single joined entity before being split apart (21:30), this primal water functioned as the raw, undifferentiated field from which cosmic separation, ordering, and formation became possible. The Qur’an’s language suggests that water represents the earliest “matrix” of creation — the fluid ground of being upon which the architecture of the universe was laid.

Modern cosmology, surprisingly, mirrors this language more than it may seem. Physicists speak of an early universe filled with an ultra-dense, superheated plasma — a fluid-like state that behaved not as particles but as a continuous medium. In the first fractions of a second, this cosmic “fluid” expanded, cooled, and differentiated into the building blocks of matter. From a scientific perspective, the universe itself began in a formless, flowing state before giving rise to stars, galaxies, and planets. In this sense, when the Qur’an describes the Throne of God resting upon a primordial “water,” it is capturing the idea that creation began from a unified, fluidic foundation — a state without structure but filled with the potential for all structures.

This cosmic water is not H₂O, but it functions as the archetype of fluidity, malleability, and potential. Just as earthly water is the basis for biological life, the primordial water is portrayed as the basis for cosmic life — the motherboard of physical existence. Seen in this way, Qur’anic cosmology and modern cosmology do not contradict each other; they simply describe the same mystery in different languages. Revelation calls it “water,” science calls it “primordial plasma,” but both point toward a single truth: the universe began in a unified medium from which all diversity emerged. The Qur’an thus frames creation as a journey from fluidity to form, from undifferentiated essence to structured cosmos — a narrative that parallels the scientific understanding remarkably closely.

How does modern science interpret this idea of a single, fluid origin for all existence?

Modern science, far from contradicting the Qur’anic concept of a unified watery origin, has arrived at a remarkably similar conclusion: the universe emerged from a single, undivided, fluidic state. Physicists describe the earliest moments after the Big Bang as an era when matter had not yet taken shape — no atoms, no solids, no gases, not even light as we recognize it. Instead, the cosmos was filled with a superheated, dense plasma: a flowing, continuous medium where particles had no fixed identity. In this sense, the universe began not as a structured machine but as a kind of cosmic “ocean,” a primal sea of energy. As it expanded and cooled, this fluid differentiated into quarks, electrons, and eventually the atoms that form stars, planets, and living creatures. Astrophysics even suggests that the fundamental forces themselves — gravity, electromagnetism, and the nuclear forces — emerged from this unified broth. From this point of view, everything that exists today, from the iron in your blood to the photons in a distant galaxy, traces its lineage back to a single, formless, fluid-like state.

This scientific narrative intriguingly parallels the Qur’anic imagery of creation emerging from a primordial “water.” While science uses mathematical metaphors and revelation uses symbolic language, both describe the same structural truth: multiplicity arises from unity. In biology, the theme repeats itself. The human body begins as a tiny drop of fluid — a microscopic, water-rich cell that divides again and again until an entire human being is formed. Every biological process, from cell division to energy transport, depends on water’s unique molecular behavior. Life, in the scientific sense, is not simply surrounded by water — it is inseparable from it. Whether viewed through the scriptural lens of a primordial ocean beneath the Throne or the scientific lens of a cosmic plasma preceding the stars, both perspectives converge on a shared insight: everything begins in fluidity, and form is only the latest chapter in a much older story.

How does the human body emerge from this water-based creation?

The human body begins in the same language of fluidity that shaped the universe itself. The Qur’an describes human origins repeatedly in terms of water: a “drop of fluid” (16:4), a “mingled drop” (76:2), and a “gushing water” (86:6). These descriptions are not poetic flourishes but precise biological realities. Modern embryology confirms that human life starts as a microscopic, water-rich cell suspended in a fluid environment. This cell divides, multiplies, and organizes itself through biochemical reactions that occur exclusively in water. The early embryo floats in amniotic fluid — a sealed, protective ocean that mirrors the primordial oceans of early Earth. Even as the fetus grows, every cell it forms is essentially a tiny bag of structured water, its chemistry entirely dependent on the movement and arrangement of water molecules.

By adulthood, nearly seventy percent of the human body is water; nearly every physiological function is a tribute to its presence. Blood is water-based; lymph is water-based; digestion, respiration, nerve conduction, and temperature regulation all depend on precise water balance. The Qur’anic insistence that humans were created from water is not only correct in the metaphorical sense — it is anatomically and chemically accurate. From the moment of conception to the final breath, the human body is a water-dependent system: a constellation of cells held together and animated by the same element that once filled the newborn universe. Water is not simply a component of life; it is the stage upon which life is acted out. The body is, in the deepest sense, a living expression of water’s ability to shape form, carry energy, store memory, and sustain existence.

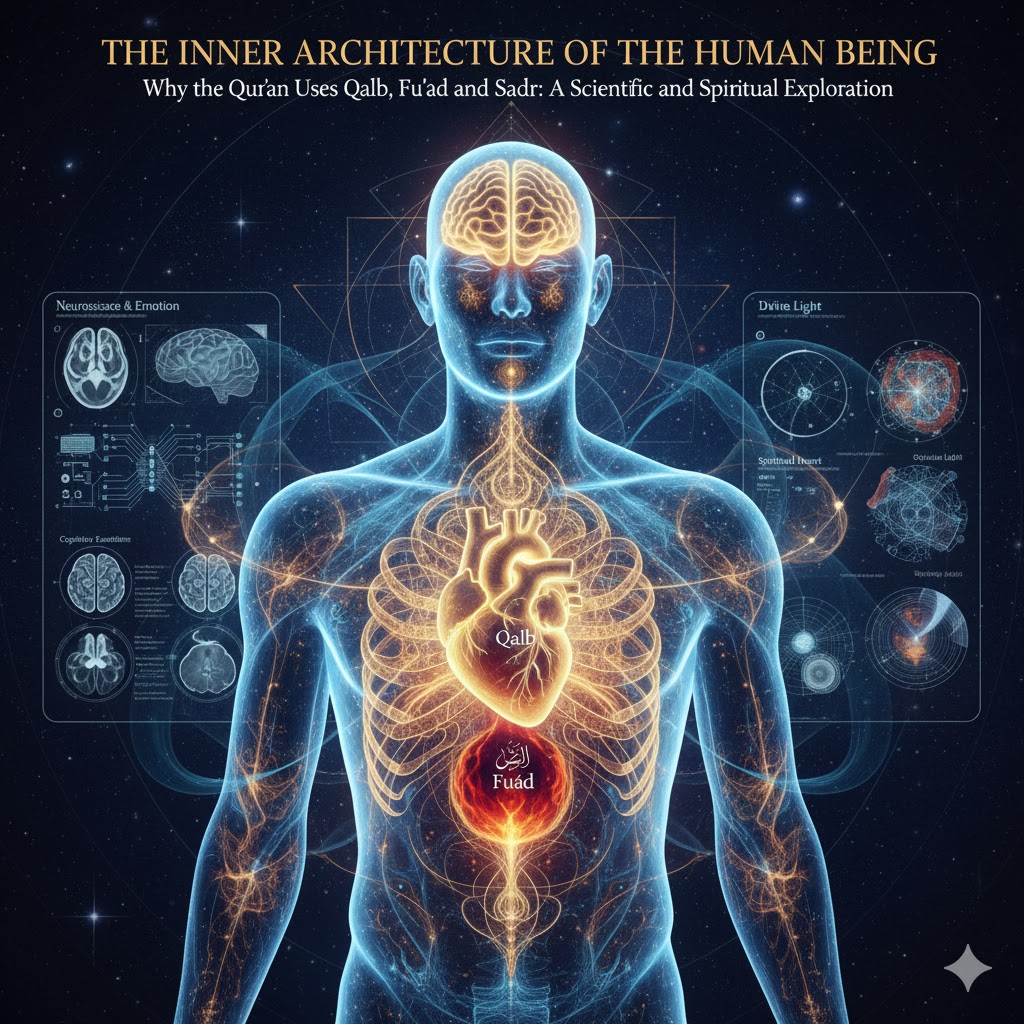

What is the inner software of the human being — the soul, the self, the heart, and the life-force?

If the body is the hardware crafted from water and clay, then its software is an intricate constellation of unseen realities: the soul, the self, the heart, and the life-force. These elements, though invisible, shape human experience far more profoundly than muscles, bones, or neurons. The Qur’an distinguishes each of these layers with remarkable precision. The soul (rūḥ), described in the verse “The soul is of the command of my Lord” (17:85), is not a product of physical creation. It does not emerge from water or matter; it is breathed into the human form as a divine command — an infusion of consciousness and higher awareness. It is the luminous core that grants the human being the ability to perceive meaning, truth, intention, and transcendence.

But the soul alone does not define human interiority. There is also the self (nafs), the evolving psychological identity that learns, desires, fears, and chooses. The Qur’an speaks of various states of the self — from the lower self that inclines toward desire (12:53), to the self that reproaches itself morally (75:2), and finally the serene self invited to return to its Lord (89:27–30). The self is not a fixed entity; it is shaped by life’s experiences, habits, impulses, and moral choices. It grows or deteriorates depending on what it absorbs, just as the body grows or weakens according to what it consumes.

Between the soul and the self stands the heart (qalb) — the spiritual and moral command center. The Qur’an attributes understanding, clarity, blindness, faith, and deviation to the heart, not the brain. “They have hearts with which they do not understand” (7:179), and “It is not the eyes that become blind but the hearts within the chests” (22:46). In this view, the heart is not merely an organ that pumps blood but the locus where intention, direction, sincerity, and guidance take shape. It is where the soul’s light or the self’s shadows are received, processed, and turned into decisions.

Finally comes the life-force (ḥayāt), the animating energy that keeps the human body alive even when consciousness sleeps. This biological vitality is distinct from the soul: people can be unconscious, anaesthetized, or deeply asleep with their souls in a state of partial withdrawal, yet the life-force continues to drive respiration, circulation, and cellular function. The Qur’an says, “Allah takes the souls at the time of death and those that do not die in their sleep” (39:42), indicating that life can persist even when the soul’s connection is temporarily loosened. The life-force is sustained by the water-based chemistry of the body — oxygen, nutrients, and cellular reactions — but its continuity is ultimately governed by divine will.

Together, these four dimensions create the human interior. The body is the vessel, the life-force the engine, the self the traveler, the heart the navigator, and the soul the light by which the path is seen. A human being is not merely an organism of water and carbon but a layered being whose physical, psychological, moral, and spiritual realities interlock with extraordinary harmony. This multi-dimensional composition is what gives humanity its complexity, its struggle, and its potential — the ability to rise toward the divine or fall toward the base. In this inner software, revelation and consciousness meet, making the human being the most intricate creation in the universe.

How does evolutionary theory relate to the Qur’anic narrative of creation and our findings about water, life, and human interiority?

The debate around evolution often collapses into a false choice: either life emerged through a gradual natural process, or it appeared suddenly by divine command. Yet when we place the Qur’anic narrative beside modern scientific discovery, a more nuanced and coherent picture emerges—one in which both can coexist without contradiction. Evolutionary biology describes life as unfolding through stages: simple organisms appear in water, diversify, adapt, and eventually give rise to complex beings. The Qur’an, strikingly, also speaks of creation in stages (“He created you in stages” 71:14), of living creatures emerging first from water (21:30), and of the human being passing through successive transformations in the womb (23:12–14). In this layered structure, evolution and revelation converge on the same principle: creation is a process, not an accident.

Where they diverge is the final leap: the emergence of the human being not merely as a biological organism but as a creature endowed with consciousness, moral agency, and soul. Evolution explains how the human body may have developed; the Qur’an explains how the human being became human. The verse “When I have shaped him and breathed into him of My spirit” (15:29) marks a moment that evolutionary theory cannot account for, because no biological mechanism produces consciousness, self-awareness, or moral perception. Science can trace the body through time, but it cannot explain the soul, the self, or the heart—the inner software that defines human uniqueness.

Our exploration of primordial water, cosmic origins, and inner architecture reveals this dual-layer reality. Evolution describes the unfolding of physical forms out of earlier forms, consistent with the Qur’an’s portrayal of creation as a progressive, water-based emergence. But evolution cannot explain the infusion of rūḥ (soul), the formation of the nafs (self), the moral agency of the qalb (heart), or the metaphysical significance of life-force. These are not products of natural selection but expressions of the divine command that completed the human being.

Thus, the harmony between the two narratives lies in understanding their domains: evolution addresses the how of physical formation, while the Qur’an addresses the why and the who. Science traces the journey of water becoming life; revelation explains how life becomes a person. When viewed together, they reveal a remarkably coherent story—one in which the human body belongs to the continuity of nature, while the human soul belongs to the breath of the Divine. Far from being in conflict, the two perspectives complete one another, offering a fuller understanding of what it means to be human: a creature shaped by the waters of the earth, awakened by the breath of heaven.

Where does science reach confusion, and what are the limits it cannot cross?

Despite its extraordinary progress in mapping the physical universe, modern science ultimately stands baffled before three fundamental mysteries: the origin of life, the emergence of consciousness, and the nature of the self. Biologists can describe how molecules interact, how cells divide, and how DNA encodes information, but they cannot explain how non-living matter first became alive. The question that haunts every laboratory—“What sparked the first living cell?”—remains unanswered. Theories exist, but evidence does not. Life requires water, energy, and chemistry, yet none of these ingredients alone produce life; the transition from inert matter to a living organism is a leap science cannot account for. The Qur’an, by contrast, does not attempt to reduce life to chemistry. It states plainly, “He gives life and causes death” (57:2), acknowledging life as a divine act that lies beyond material causation.

Even more puzzling to science is consciousness. Neuroscience can map electrical impulses in the brain, but it cannot explain why those impulses produce subjective experience. How does a cluster of neurons give rise to memory, emotion, awareness, intention, or the sense of self? Why does the human being perceive meaning, beauty, or morality—qualities that no physical measurement can capture? This gap is so troubling that leading scientists now call consciousness “the hard problem”—a mystery that resists every form of physical explanation. The Qur’an, however, frames consciousness as the result of a divine breath: “I breathed into him of My spirit” (15:29). What science calls confusion, revelation calls the boundary of the unseen.

Finally, the nature of the self—the inner voice that chooses, hopes, regrets, and aspires—remains outside scientific grasp. Psychology can describe behavior, but it cannot locate the self in any organ or cell. It cannot explain why the mind judges right and wrong, why the heart carries guilt or serenity, or why humans seek meaning at all. The Qur’an names this inner entity nafs and presents it as a moral agent shaped by intention and guided by the heart. In this realm, science has no tools; it cannot quantify conscience.

Thus, the scientific worldview, despite its power, stands silent before life, consciousness, and the self. These are not failures of science—they are boundaries that mark where material description ends and metaphysical truth begins. Revelation steps in not to contradict science but to complete the picture, offering language for the realities that science cannot reach. At these intersections of confusion, the Qur’an does not compete with science—it provides the missing vocabulary for a universe that is deeper than matter and richer than mechanism.

Where does philosophy reach its limits, and why can it not resolve the deepest questions of existence?

Philosophy has spent millennia wrestling with the same mysteries that challenge science—life, consciousness, purpose, morality, and the nature of the self. Yet, despite its depth and brilliance, philosophy ultimately reaches a frontier it cannot cross. Philosophers can describe the structure of thought, analyze the logic of being, and probe the nature of reality, but they cannot produce final answers. Every philosophical claim generates a counter-claim; every school becomes the critique of another. For every Plato, there is an Aristotle; for every Descartes, a Nietzsche; for every rationalist, an empiricist waiting in opposition. The result is a perpetual oscillation between ideas without definitive truth. Unlike the empirical world, where evidence can settle disputes, philosophical arguments remain suspended in abstraction.

The limits become most visible when philosophy confronts the origin of life and the emergence of consciousness. Philosophers can debate whether the mind is material or immaterial, whether free will exists, or whether morality is objective, but they cannot settle these issues. The problem is not lack of intelligence; it is lack of access. Philosophy is limited to the tools of reason, and reason itself is built upon assumptions that it cannot justify. Why is logic valid? Why does consciousness perceive meaning? Why does the human heart recognize beauty or moral truth? These are experiences, not equations—and reason can describe them but not originate them. As the Qur’an puts it, “They encompass nothing of His knowledge except what He wills” (2:255), marking a boundary that pure intellect cannot cross.

The same limitation appears when philosophy attempts to explain the self. Thinkers can argue whether the self is an illusion, a process, or an essence, but no philosophical framework can explain why the human being feels guilt, hope, fear, love, or purpose. These experiences are too interior, too existential to be reduced to argument. The Qur’an situates them in the qalb—the moral and spiritual heart—not in logic. Moreover, philosophy cannot account for revelation, for mystical experience, or for the soul. It can analyze concepts but cannot reach into metaphysical realities because it lacks the tools to engage the unseen. Its instrument is reason, and reason is powerful but finite.

Thus, philosophy’s limits are not failures; they are boundaries built into the human intellect. Philosophy can raise profound questions, highlight contradictions, refine thought, and challenge assumptions—but it cannot deliver ultimate truths about life’s origin, consciousness, purpose, or destiny. These truths belong to the domain of the unseen (al-ghayb)—a realm that philosophy can gesture toward but never enter. At that threshold, revelation becomes not an opponent of philosophy but its completion, offering certainty where speculation must stop. Reason can take us to the edge of the cliff, but only revelation can show what lies beyond.

Why do we trust the Qur’an on this subject when science and philosophy remain confused?

We trust the Qur’an not because science is limited or philosophy is uncertain, but because the Qur’an speaks with a kind of clarity that neither science nor philosophy can reach. Science describes how things work but cannot say why they exist. Philosophy asks why, but cannot prove any final answer. The Qur’an stands where both disciplines falter: it speaks from beyond the system being examined. It is not a hypothesis looking for evidence, nor an argument waiting for rebuttal. It is a declaration from the Author of the system — a perspective unavailable to human reasoning or empirical tools. When the Qur’an describes the origins of life, consciousness, the self, the soul, or the moral heart, it does so with a certainty that no human discipline can match, because the Qur’an does not emerge from human speculation; it claims to emerge from the Source of existence itself.

The logic for believing the Qur’an rests on three foundations: epistemic, historical, and experiential.

Epistemically, the Qur’an offers information about realms that are inherently inaccessible to human investigation. No scientist can enter the pre-creation state of the universe; no philosopher can reach into the unseen metaphysical structure of the soul. When revelation speaks about these realities — the primordial water, the divine breath, the layers of the self, the workings of the heart — it provides knowledge from a vantage point reason cannot climb to. If science can only describe mechanisms and philosophy can only debate ideas, the Qur’an provides the missing category: authoritative knowledge of the unseen (al-ghayb).

Historically, the Qur’an presents a record of intellectual precision unmatched by any text of its era. It speaks of embryology, cosmology, water’s centrality to life, the expanding universe, the barrier between salt and sweet waters, and the layered nature of the human psyche — all centuries before these ideas entered scientific discourse. It does not offer myths; it offers verifiable principles. The very fact that its claims about water as the basis of life, or the layered construction of the human mind, now align with cutting-edge science suggests that its insights come from a source beyond 7th-century Arabia. When two lines of knowledge — revelation and empirical discovery — independently converge, the rational mind is compelled to take notice.

But the strongest logic is experiential. The Qur’an does not merely describe the universe; it describes us with a precision that no scientific instrument and no philosophical theory can match. It speaks to our inner lives — our guilt, fear, yearning, conscience, hope, and sense of meaning. It identifies the heart as the true center of moral decision, the self as a developing inner traveler, the soul as the divine spark, and life as a trust. People believe the Qur’an because it interprets their interior experience better than any discipline ever has. A text that describes both the outer world and the inner world with accuracy is not offering human opinion; it is offering truth.

Thus, belief in the Qur’an on this subject is not a leap of blind faith but an act of intellectual consistency. When science confesses confusion over the origin of life, when philosophy admits uncertainty over consciousness and selfhood, and when human experience points toward realities beyond matter, the Qur’an completes the picture. It does not replace science or philosophy; it positions them within a larger framework. Science tells us how creation unfolds; philosophy explores its ideas; the Qur’an reveals the reality behind both. At the intersection of their limits, the Qur’an stands not as an alternative but as the explanation — the voice that speaks from the Source of life itself.

Conclusion: A Universe Rooted in Water, A Human Rooted in Meaning

Where All Knowledge Meets, and Where the Qur’an Speaks Beyond Them

In the final analysis, the story of existence becomes clearest when we place science, philosophy, and revelation side by side. Science traces life back to water, to a cellular ocean, to a primordial cosmic fluid. Philosophy asks why anything exists at all, but never arrives at a final answer. Both disciplines illuminate part of the picture, but both ultimately reach a boundary they cannot cross. Science cannot explain how life emerged from non-life, why consciousness exists, or what the self truly is. Philosophy cannot resolve the nature of the soul, the purpose of life, or the foundation of morality. They bring us to the edge of the cliff — but not beyond it.

It is precisely at this frontier that the Qur’an enters the conversation, not as a competitor to science or a replacement for reason, but as a source that speaks from beyond the limits of both. When the Qur’an declares that “We made from water every living thing,” and that the Throne itself rested upon a primordial water, it describes a layered reality that science only now begins to glimpse. When it speaks of the human being shaped from clay yet awakened by a divine breath, it explains the distinction that evolutionary theory cannot: the difference between a body that evolves and a consciousness that cannot be reduced to biology. When it distinguishes between the soul, the self, the heart, and the life-force, it offers a vocabulary for inner experience that philosophy has sought for thousands of years but never fully captured.

The human being is therefore not an accident of matter nor a riddle of mind alone. The body belongs to the continuity of creation, the self grows through experience, the heart chooses direction, the life-force sustains the organism, and the soul connects the human to the realm beyond physical explanation. In this harmony of physical origins and metaphysical purpose, revelation offers what science and philosophy cannot: not an alternate theory, but a completed picture.

To believe the Qur’an in this domain is not to abandon reason — it is to acknowledge its limits. It is to recognize that when empirical tools grow silent and logical arguments exhaust themselves, the Qur’an speaks with a clarity rooted not in speculation, but in authorship. It describes the universe not from within the system, but from the perspective of the One who brought the system into being. And so, creation begins in water, unfolds through natural processes, receives consciousness through divine breath, and culminates in a creature who carries both earth and heaven within himself. At that intersection — where matter becomes meaning — the human being discovers the truth of his origin, the purpose of his journey, and the direction of his return.