The Mystic Massacre stands as one of the most harrowing and transformative events in early American history—a night of fire, fear, and devastating loss that reshaped the balance of power in 17th-century New England. Long before the United States was imagined, before colonial institutions had fully taken root, the fragile coexistence between English settlers and Indigenous nations was already fracturing under the pressures of expansion, economic rivalry, cultural misunderstanding, and mutual distrust. Within this volatile environment, the Pequot people, one of the region’s most influential Indigenous nations, found themselves at the center of a dramatic confrontation that would alter the course of their history forever.

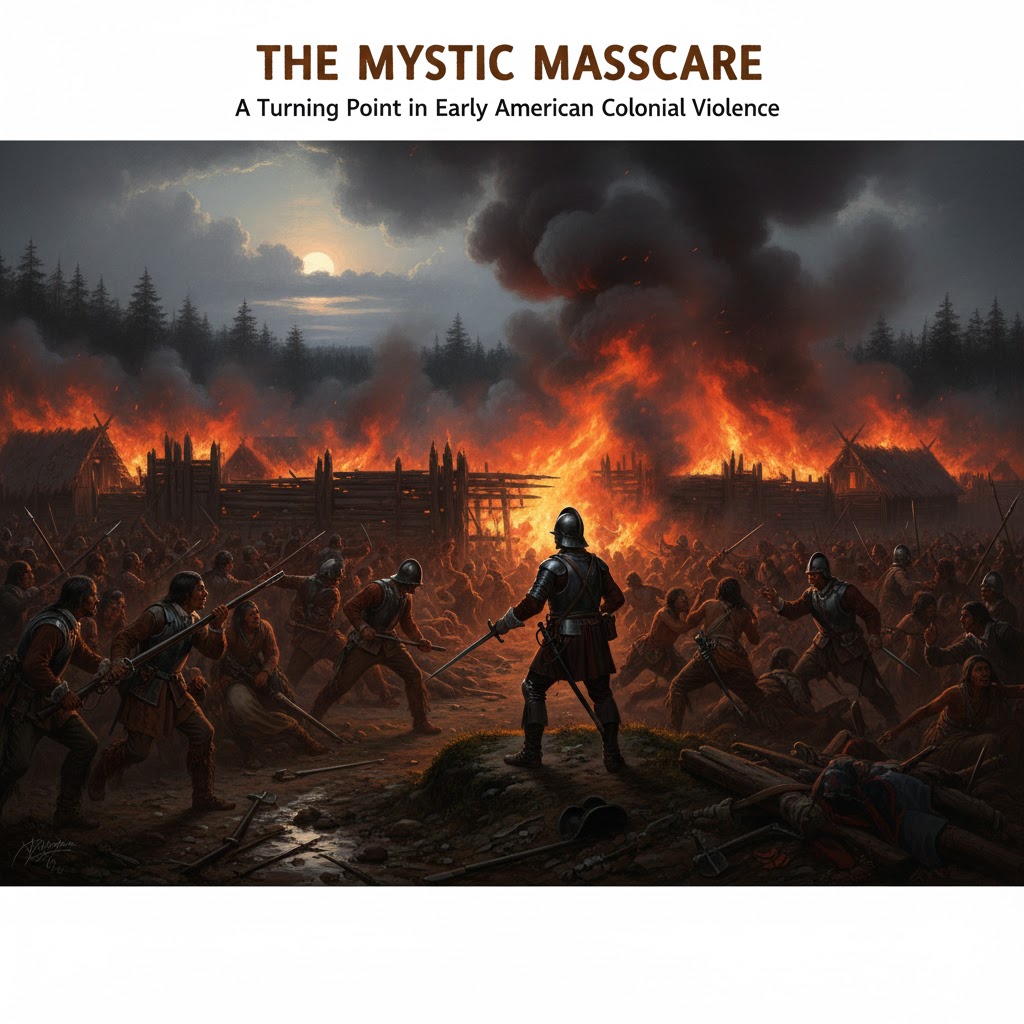

On the dawn of May 26, 1637, English Puritan soldiers and their Indigenous allies launched a sudden, coordinated attack on the principal Pequot settlement near the Mystic River. What unfolded was not a conventional battle but a sweeping annihilation—an assault on a fortified village that left hundreds of men, women, and children dead within an hour. The English set fire to the palisade, trapping families inside, and methodically killed those who tried to escape the flames. Captain John Mason later wrote that the village was turned into “a fiery oven,” a description that continues to haunt accounts of the massacre.

This event was not an isolated tragedy. It marked a turning point in the Pequot War, the first major armed conflict between Indigenous peoples and English colonists in New England. More importantly, the massacre set a precedent for future colonial policies, legitimizing the use of overwhelming force against Indigenous communities and reinforcing the settlers’ belief in their divine and territorial entitlement. For the Pequots, it was an existential catastrophe—one that shattered their political autonomy, decimated their population, and attempted to erase their cultural identity.

Four centuries later, the Mystic Massacre remains a subject of intense historical reflection and ethical debate. Scholars, Indigenous leaders, and educators view it not only as an episode of brutal warfare but as an early example of settler-colonial violence and cultural suppression. Its legacy continues to shape conversations about American identity, historical memory, and the long struggle for Indigenous recognition.

1. Background: Tensions in Early New England

By the 1630s, English settlers in the Connecticut River Valley were expanding rapidly. At the same time, the Pequots—a powerful Indigenous nation controlling trade routes from Long Island Sound—were facing rising pressure from:

- English colonial expansion

- Shifting trade alliances with Dutch and Indigenous groups

- Competition with neighboring tribes such as the Narragansett and Mohegan

The atmosphere was tense. Disputes over land, trade, and cultural practices escalated into raids, retaliation, and mistrust. When English traders were killed in incidents involving Indigenous groups, settlers blamed the Pequots—sometimes without clear evidence—pushing both sides toward open conflict.

2. The Road to Violence: The Pequot War

The Pequot War (1636–1637) is widely recognized as the first major armed conflict between Indigenous peoples and English colonists in New England—a pivotal confrontation that set the tone for centuries of contested relationships between Native nations and European settlers. Far from being an inevitable clash, the conflict emerged from a complex web of economic competition, shifting alliances, cultural miscommunication, and mutual suspicion. By the time hostilities reached their peak, the Pequots were not simply fighting for land or trade—they were fighting for their political survival.

1. Trade Rivalry: Wampum, Fur, and Economic Power

In the early 17th century, wampum—intricately crafted shell beads used as currency and a symbol of diplomacy—was the backbone of Indigenous commerce throughout the region. Whoever controlled its production and distribution held tremendous influence.

- The Pequot nation, located strategically along coastal trade routes, dominated the flow of wampum and fur trade with both Dutch and English traders.

- The English colonists of Connecticut, eager to expand their economic reach, viewed Pequot control as both an obstacle and a threat.

- Competition between European powers—particularly Dutch traders in the Hudson River Valley—added fuel to the rising tension.

The more the English sought economic independence, the more the Pequots saw their territory and authority challenged.

2. Indigenous Power Struggles and Shifting Alliances

The Pequots were not the only major Indigenous nation in the region. Their relationship with surrounding tribes was shaped by longstanding political dynamics.

- The Mohegans, led by sachem Uncas, had split from the Pequot nation and were eager to weaken their former rivals.

- The Narragansett of present-day Rhode Island, another powerful nation, saw Pequot influence as a threat to their regional standing.

- Smaller groups, caught between larger powers, shifted alliances depending on trade access, security, or survival.

These preexisting tensions meant that English colonists could form strategic alliances with Indigenous nations who had their own motivations for opposing the Pequots. The colonists took advantage of this political landscape, aligning themselves with the Mohegans—and later the Narragansetts—to isolate and weaken the Pequot nation.

3. Puritan Fears and the Logic of Preemptive Violence

For the Puritan settlers, fear was not simply emotional—it was ideological. They believed they were a chosen people tasked with building a divine society in the New World. Any challenge, especially from Indigenous nations who held both military strength and territorial knowledge, was interpreted through the lens of religious destiny and existential danger.

Several incidents intensified Puritan anxieties:

- The deaths of English traders, such as John Oldham and John Stone, were blamed—sometimes incorrectly—on the Pequots.

- Puritan leaders saw Indigenous retaliation or self-defense as signs of rebellion or “hostility against God’s people.”

- Sermons and political speeches increasingly portrayed the Pequots as a threat that needed to be subdued before they became unmanageable.

This worldview laid psychological groundwork for preemptive and disproportionate violence.

4. Cultural Misunderstandings and Conflicting Concepts of Justice

Colonists and Indigenous nations did not share the same systems of diplomacy, law, or conflict resolution.

- Indigenous justice emphasized restoration, compensation, and negotiated peace.

- English justice emphasized individual guilt, punishment, and retribution.

- When misunderstandings occurred, colonists often interpreted Pequot diplomacy as avoidance or defiance.

These differences meant that even small disputes could quickly escalate into larger confrontations. When the Pequots attempted to resolve early conflicts through traditional diplomatic channels, the English misread these gestures as evasions—deepening mistrust on both sides.

The Decision to Destroy Pequot Power (Spring 1637)

By early 1637, the situation reached a breaking point. The English colonies of Connecticut and Massachusetts Bay had suffered raids, some of which were attributed to Pequot warriors. Although the reasons for these attacks were contested and sometimes misunderstood, colonists interpreted them as coordinated aggression rather than isolated responses to provocation.

At the same time:

- Mohegans, under Uncas, openly aligned with the English, offering military support against their former kin.

- Narragansetts, after negotiation, reluctantly joined the English coalition, fearing that if the Pequots prevailed, they would be next in line.

Together, colonial officials and their Indigenous allies agreed that the Pequot nation needed to be “broken”—a term used by English officials to signify total military defeat, the dismantling of political authority, and the removal of their influence from the region.

This decision set into motion a brutal military campaign that culminated in the Mystic Massacre—an event that not only devastated the Pequot population but signaled a dramatic shift in the balance of power that would define colonial-Indigenous relations for generations.

3. The Mystic Massacre: May 26, 1637

Before dawn, English forces led by Captain John Mason and Captain John Underhill, along with hundreds of Indigenous allies, surrounded the main Pequot village near the Mystic River in present-day Connecticut.

What happened inside the fort

The Pequot village at Mystic was a heavily populated, fortified settlement, enclosed by a palisade of sharpened wooden stakes and interwoven barriers meant to protect families from rival tribes—not from the kind of attack that unfolded on the morning of May 26, 1637. Within those walls lived an estimated 400 to 700 Pequot men, women, children, and elders. Many had sought refuge there in recent days, believing the fort to be one of the safest places during the rising tensions of the war.

Before dawn, English forces led by Captain John Mason and Captain John Underhill, accompanied by hundreds of Mohegan and Narragansett warriors, encircled the settlement. Moving through the early morning mist, they approached the village quietly and strategically, dividing into groups to surround the exits and block any chance of escape.

1. The Attack Begins

The English initiated the assault by storming the entrances to the fort. Initial fighting occurred at close quarters:

- Pequot warriors, roused abruptly from sleep, tried to mount a defense with limited weapons.

- Women shielded children and sought hiding places, unaware that escape would soon become impossible.

- Confusion spread rapidly through the village as the English forces breached the palisade.

The colonists quickly realized the village was too heavily defended for hand-to-hand combat to achieve swift victory. Captain Mason made a decision that would turn the attack into one of the most devastating events in early American colonial history.

2. The Setting of the Fire

Recognizing the challenge of clearing the fort by force, Mason ordered the burning of the settlement. His men set fire to the wigwams—long, bark-covered homes—using torches and gunpowder. Flames rapidly consumed the dry wooden structures, and strong winds intensified the blaze.

Within minutes:

- Smoke billowed through the fort, making it impossible for families inside to see clearly.

- Flames spread from home to home, fueled by tightly clustered dwellings and stored supplies.

- Children’s cries mixed with shouted prayers and screams, as panic overtook order.

The palisade, once a protective barrier, now became an inescapable wall trapping the inhabitants inside a burning enclosure.

3. Blocking the Escape Routes

As the fire raged, Pequot civilians tried desperately to escape through gaps or entrances in the palisade. But the English had anticipated this:

- Armed colonists waited outside the exits, shooting anyone who fled.

- Some Pequot tried to scale the walls, only to be shot or stabbed as they dropped to the ground.

- Mohegan and Narragansett warriors—though initially shocked by the scale of the colonists’ violence—also participated in attacks on those who escaped.

For many, there was no safe direction to run. The only choices were to die by the bullet or by the flames.

4. Death Within the Flames

Inside the fort, the heat became unbearable. Contemporary accounts describe the roaring of the fire, the collapse of burning structures, and the suffocating smoke that filled every corner of the settlement.

Those who stayed inside in hopes of shelter or protection found themselves trapped as:

- Woven mats and bark walls ignited instantly.

- Stored food, tools, and household goods exploded or burned.

- The fire consumed nearly every wigwam in the village.

Most of the hundreds who died that morning perished inside the flames, not by the sword.

5. Eyewitness Reactions: Horror, Shock, and Justification

Surviving accounts reveal different emotional reactions:

- Indigenous allies, particularly the Narragansetts, were horrified. They reportedly cried out that the English had gone too far, calling the massacre “too furious” and beyond the customs of warfare practiced among Indigenous nations.

- English soldiers, though some expressed shock, largely interpreted the event through a religious framework that converted violence into divine sanction.

Captain John Mason, the principal English commander, later wrote that the burning fort was:

“a fiery furnace… a severe act of God.”

He described the deaths as an instrument of divine judgment against what he considered a dangerous and “heathen” nation. His writing reflects the Puritan worldview that framed colonial success as evidence of God’s favor, regardless of the methods used. This religious interpretation helped justify the scale of destruction, shaping colonial narratives for years to come.

6. The Aftermath Within the Fort

By the time the flames died down:

- Nearly the entire population of the fort lay dead.

- The bodies of families, warriors, elders, and children were mixed with smoldering debris.

- The fort was reduced to charred earth, ashes, and collapsed palisade posts.

It was one of the deadliest mass killings in the region’s history and effectively destroyed the political power of the Pequot people.

Eyewitness accounts describe the scene as catastrophic—homes burning, families trapped, and bodies piling up. Mason later wrote that the attack was “a fiery furnace” and described the deaths as an act of divine judgment, reflecting Puritan religious framing rather than humanitarian concern.

Casualties

Historians estimate that between 500 and 700 Pequots were killed within an hour—most of them noncombatants.

The event is now widely recognized as a massacre, not a battle.

4. Aftermath: The Destruction of the Pequot Nation

The massacre did not end the war immediately, but it destroyed the political and military power of the Pequot nation.

Consequences

- The English and their allies hunted down survivors in the following weeks.

- Pequot villages were destroyed, and survivors were executed, enslaved, or distributed to allied tribes.

- The Treaty of Hartford (1638) outlawed the very use of the word “Pequot,” attempting to erase the tribe’s identity.

This was a clear case of cultural and political suppression, reflecting early patterns of settler-colonial violence.

5. Long-Term Impact: A Blueprint for Colonial Expansion

The Mystic Massacre shaped the trajectory of colonial policy in several ways:

A. Normalizing total warfare against Indigenous peoples

Future conflicts—King Philip’s War (1675–1676), the Powhatan conflicts, and later frontier wars—were influenced by the precedent that entire Indigenous communities (including civilians) could be targeted.

B. Strengthening English alliances

The English used the massacre to cement political alliances with the Mohegan and Narragansett, although those alliances shifted over time.

C. Expanding colonial confidence

The victory gave English settlers the assurance—politically and militarily—to expand deeper into Native land.

D. Shaping narratives of “divine mission”

Puritan leaders used the massacre to justify their presence as part of a divine plan, ignoring the moral implications of the violence.

6. Modern Interpretations: Genocide, Memory, and Reconciliation

Today, many scholars and Indigenous voices describe the Mystic Massacre as an act of genocide or ethnic cleansing, given that:

- a civilian population was deliberately targeted

- an entire nation was nearly eradicated

- survivors were enslaved or forbidden from identifying as Pequot

The Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation (descendants of survivors) maintains museums, documentation, and cultural preservation initiatives to ensure the history is neither forgotten nor distorted.

The massacre is now part of public education, memorials, and Indigenous rights discussions in the United States.

7. Conclusion: Why the Mystic Massacre Still Matters

The Mystic Massacre was more than a tragic episode—it was a turning point in the relationship between Indigenous peoples and European settlers. It revealed the violent foundations of colonial expansion, the fragility of early cross-cultural relationships, and the devastating consequences of fear-driven policy.

Understanding this history is essential not only to honor the victims but to recognize how early patterns of injustice shaped centuries of Indigenous-colonial relations. It reminds us that historical memory is not just about the past—it informs the ethics, policies, and reconciliation efforts of the present.