Introduction: The Living History of Punjabi Festivals

Punjabi festivals are far more than moments of celebration; they are living archives of Punjab’s history, climate, and collective memory. Long before written records, the people of Punjab marked time through the rhythm of seasons, the movement of the sun, and the cycles of sowing and harvest. Festivals emerged as a natural response to survival, gratitude, and hope—binding communities together through shared labor, shared food, and shared belief.

Rooted deeply in an agrarian way of life, Punjabi festivals evolved alongside the land itself. The fertile plains shaped by the five rivers demanded cooperation, patience, and resilience. Over centuries, these necessities transformed into traditions that celebrated hard work, bravery, generosity, and communal harmony. Fire, grain, water, music, and dance became sacred symbols—not as abstract rituals, but as reflections of everyday life.

As history unfolded, Punjabi festivals absorbed multiple layers of influence. Ancient nature worship blended with Vedic solar traditions; later, Sufi humanism and the Bhakti movement infused festivals with emotional and spiritual depth. The rise of Sikh philosophy gave festivals a new ethical foundation—centering them on equality, courage, justice, and service to humanity. Rather than replacing older customs, these influences reshaped them, creating a culture where spirituality and daily life remained inseparable.

Despite invasions, empire-building, colonial rule, and the trauma of Partition, Punjabi festivals endured. They survived because they were never imposed from above; they were owned by the people. Passed down through folk songs, oral stories, seasonal rituals, and family gatherings, each festival became a reminder of continuity in the face of change.

Today, whether celebrated in rural villages or global diasporas, Punjabi festivals continue to carry the same core message: celebration is earned through labor, joy is shared collectively, and history lives through tradition. To understand Punjabi festivals is to understand Punjab itself—its land, its struggles, and its unbreakable spirit.

🌾 Major Punjabi Festivals (Traditional & Seasonal)

- Lohri – Winter harvest festival, fire and gratitude

- Maghi (Magha) – Solar transition and Sikh historical remembrance

- Baisakhi (Vaisakhi) – Wheat harvest, Punjabi New Year, Khalsa formation

- Basant – Spring festival, renewal, kites and mustard fields

- Teeyan (Teej) – Monsoon festival celebrated by women

- Saunh / Sawan – Rainy season, fertility and folk songs

🕊️ Sikh Religious & Historical Festivals

- Gurpurab (Guru Nanak Dev Ji) – Birth anniversary of Guru Nanak

- Gurpurab (Guru Gobind Singh Ji) – Birth anniversary

- Hola Mohalla – Martial festival of courage and discipline

- Bandi Chhor Divas – Freedom and justice (celebrated with Diwali)

- Shaheedi Jor Mela – Remembrance of Sikh martyrs

- Maghi Mela (Muktsar) – Remembers the Chali Mukte

🌙 Muslim & Sufi-Influenced Punjabi Celebrations

- Urs Festivals – Sufi saints’ death anniversaries (melas at shrines)

- Eid-ul-Fitr – Celebration after Ramadan (Punjabi cultural expressions)

- Eid-ul-Adha – Sacrifice and community sharing

🎭 Folk, Cultural & Rural Melas

- Gugga Naumi – Folk festival linked to snake folklore

- Chet Festival – Arrival of spring month (Chet)

- Jor Mela Fatehgarh Sahib – Historical remembrance

- Rural Melas (Village Fairs) – Seasonal, crop-based gatherings

- Cattle Fairs (e.g., Sibi-style Melas) – Livestock, trade, and culture

🌍 Modern & Diaspora Punjabi Festivals

- Punjabi Cultural Festivals (Abroad) – Identity-focused celebrations

- Baisakhi Nagar Kirtans – Public processions in global cities

- Punjabi Folk Music Festivals – Preservation of oral tradition

Historical Roots of Punjabi Festivals: From Ancient Soil to Living Tradition

The origins of Punjabi festivals lie deep in antiquity, far earlier than organized religion or written scripture. Punjab has always been a land-first civilization, where survival depended on understanding seasons, rivers, soil, and climate. As a result, the earliest Punjabi festivals were not religious in the modern sense; they were ecological and communal responses to nature.

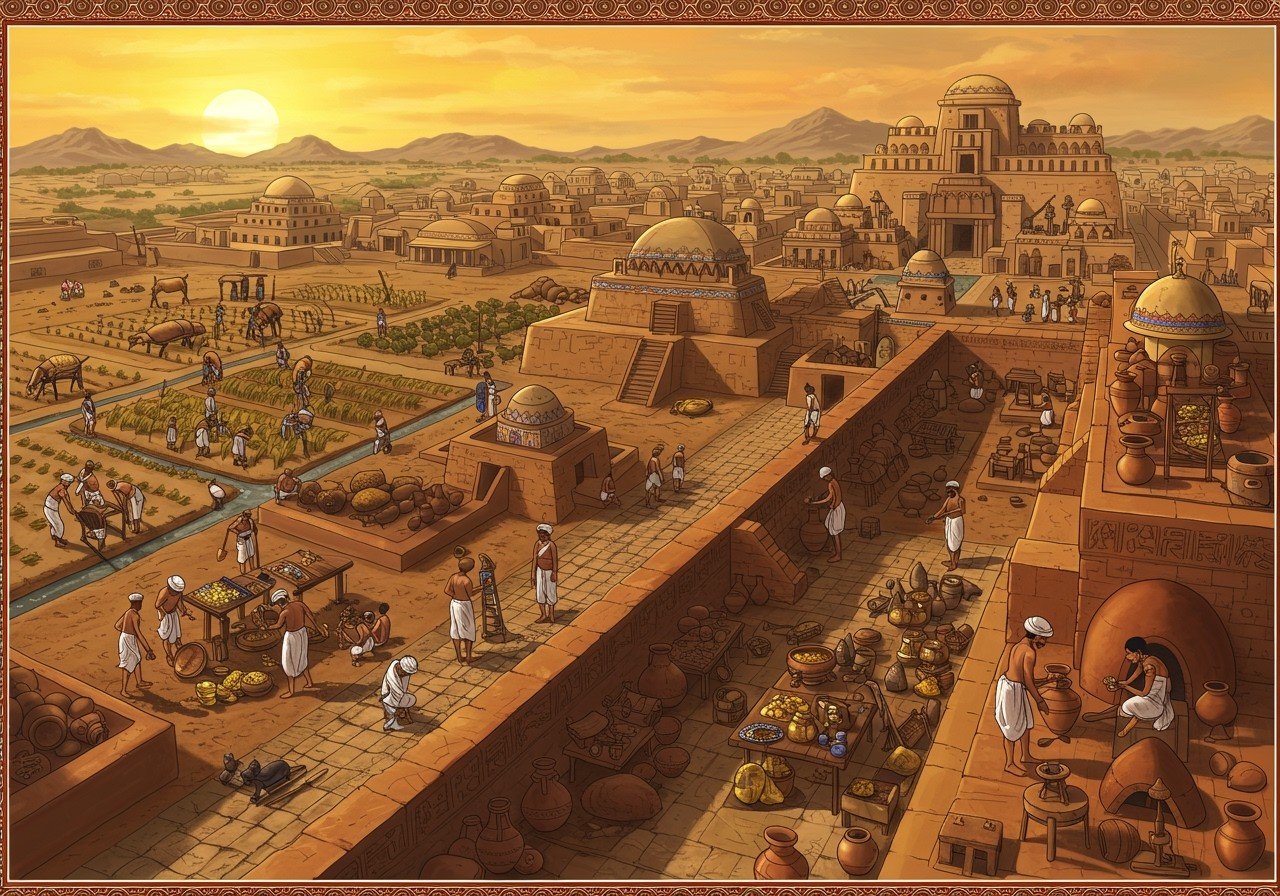

Prehistoric and Indus Valley Foundations (c. 3000 BCE)

Archaeological evidence from the Indus Valley region—closely connected to ancient Punjab—reveals a society organized around:

- Agriculture and irrigation

- Seasonal planning

- Collective labor and storage

These early communities marked critical moments such as harvest completion, winter survival, and seasonal transitions with communal gatherings. Fire rituals, food sharing, and music were central elements. These practices formed the structural blueprint of later Punjabi festivals like Lohri and Baisakhi.

Agrarian Timekeeping and Seasonal Consciousness

Unlike urban civilizations that measured time through political reigns, Punjabi rural society measured time through:

- Crop cycles (Kharif and Rabi)

- Monsoon arrival

- Lengthening and shortening of days

Festivals acted as natural calendars, signaling when to sow, reap, rest, or prepare. Celebration was never separate from work; it came after endurance and effort, reinforcing the Punjabi ethic that joy must be earned.

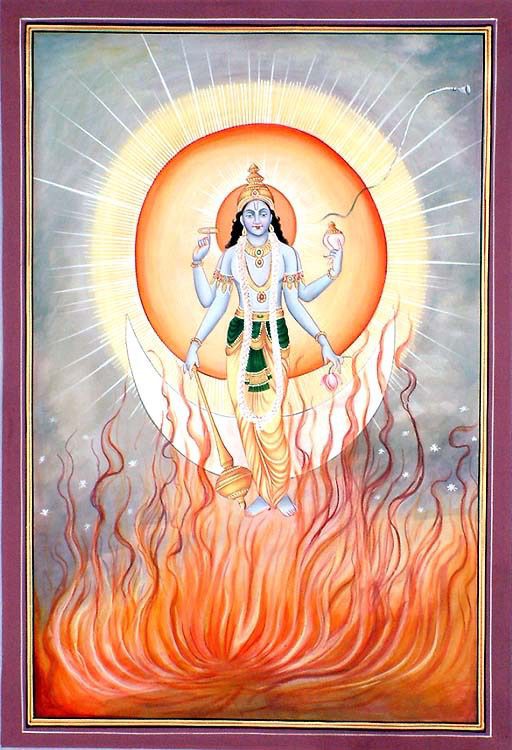

Solar and Natural Symbolism

Long before theological explanations, the sun held central importance in Punjabi life. The sun determined:

- Crop success

- Warmth during harsh winters

- Livestock survival

This is why many Punjabi festivals align with solar transitions, especially the sun’s northward movement (Uttarayan). Fire, symbolizing the sun on earth, became sacred—not as an object of worship, but as a protector, purifier, and life-giver. This symbolism remains strongest in Lohri’s bonfire tradition.

Folk Belief Systems and Oral Culture

Punjab’s festival culture developed primarily through oral transmission, not written scripture. Folk songs, seasonal chants, and village storytelling preserved meaning across generations. This allowed traditions to remain flexible, absorbing new ideas without losing their core identity.

Because of this oral nature:

- Festivals stayed inclusive

- Customs varied by region

- Community participation mattered more than ritual precision

This flexibility explains why Punjabi festivals survived centuries of political and religious change without disappearing.

Foundation for Later Religious Integration

When Vedic philosophy, Sufi thought, and later Sikh teachings entered Punjab, they did not erase these ancient festivals. Instead, they reframed them, adding moral, spiritual, and ethical meaning to practices that were already deeply rooted in daily life.

Thus, Punjabi festivals represent continuity rather than rupture—a rare cultural phenomenon where the ancient and the living coexist seamlessly.

Vedic, Folk, and Spiritual Influences on Punjabi Festivals

As Punjabi society evolved, its festivals entered a phase of cultural synthesis rather than replacement. Unlike many regions where new belief systems erased older traditions, Punjab followed a different path: integration. Ancient agrarian customs absorbed Vedic cosmology, later embraced Sufi humanism, and eventually aligned with Sikh ethical philosophy—while preserving their folk character.

Vedic Influence: Solar Cycles and Cosmic Order

With the spread of Vedic thought across North India, Punjabi festivals became more consciously aligned with cosmic and solar rhythms. The sun was no longer only a practical source of heat and growth; it also represented order (ṛta), continuity, and balance.

Key ideas introduced during this period included:

- The significance of Uttarayan (sun’s northward journey)

- Seasonal purification rituals

- Gratitude toward natural forces as sustainers of life

However, Punjab interpreted these ideas pragmatically. Rituals remained simple, collective, and seasonal—never overly priest-centric. This explains why Punjabi festivals emphasize bonfires, open-air gatherings, and communal food, rather than temple-bound ceremonies.

Folk Traditions: The Heart of Punjabi Celebration

While philosophical ideas arrived from outside, the emotional core of Punjabi festivals remained folk-driven. Village culture, oral poetry, music, and storytelling shaped how festivals were actually lived.

Folk traditions contributed:

- Seasonal songs tied to farming and weather

- Symbolic heroes representing resistance and justice

- Gendered spaces of celebration, especially for women

Festivals such as Lohri, Teeyan, and Basant preserved themes of love, longing, bravery, fertility, and defiance. Folk heroes like Dulla Bhatti emerged not as religious figures, but as moral symbols—protectors of dignity in times of oppression.

This folk foundation ensured that festivals stayed people-centered, not institution-controlled.

Sufi Influence: Humanism and Emotional Spirituality

From the 12th century onward, Sufi thought deeply influenced Punjabi cultural expression. Sufism did not introduce new festivals, but it reshaped the meaning of celebration.

Key Sufi contributions included:

- Emphasis on love, humility, and equality

- Spiritual expression through music and poetry

- Blurring of religious boundaries in communal gatherings

Shrines and seasonal fairs (melas) became spaces where celebration and spirituality merged. This influence softened rigid distinctions and reinforced the idea that joy itself could be an act of devotion.

Sikh Philosophy: Ethics, Equality, and Collective Identity

The most transformative influence on Punjabi festivals came with the emergence of Sikhism in the 15th century. Sikh philosophy did not reject seasonal or folk celebrations; instead, it reoriented them toward ethical living.

Core Sikh principles introduced into festival culture:

- Equality of all humans

- Collective responsibility

- Service (seva) as celebration

- Courage in the face of injustice

Festivals became occasions not just for joy, but for:

- Remembering sacrifice

- Reinforcing moral duty

- Strengthening communal bonds

This is why many Punjabi festivals today carry historical memory alongside seasonal meaning—combining land, labor, and legacy.

A Culture of Continuity, Not Rupture

What makes Punjabi festivals historically unique is their layered identity. Each era added meaning without erasing the past. Fire remained fire, grain remained grain, music remained music—but their symbolism deepened.

Punjabi festivals thus became:

- Seasonal markers

- Cultural memory banks

- Ethical reminders

- Social equalizers

They reflect a civilization that chose adaptation over abandonment, and continuity over rigidity.

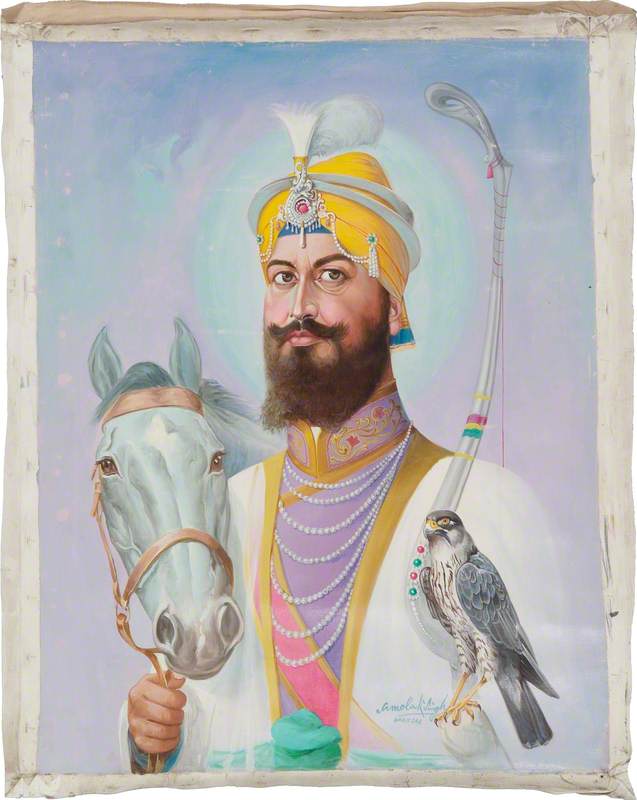

Punjabi Festivals in the Sikh Era: History, Resistance, and Identity

The Sikh era marked a turning point in the history of Punjabi festivals. What had once been primarily seasonal and folk celebrations now acquired historical consciousness and moral purpose. Festivals became occasions not only to celebrate nature and community, but also to remember sacrifice, assert identity, and reaffirm collective values in times of political pressure and social inequality.

Festivals as Ethical Institutions

The Sikh Gurus reshaped the cultural role of festivals without severing them from their roots. Celebrations were encouraged, but never as empty ritual. Instead, festivals became ethical institutions, designed to cultivate discipline, humility, courage, and service.

Key transformations included:

- Replacement of caste-based rituals with communal participation

- Emphasis on langar (community kitchen) as the center of celebration

- Integration of remembrance and moral teaching into festive gatherings

A festival was no longer just about joy—it was about responsibility.

Vaisakhi and the Birth of Collective Identity

The most defining moment in Punjabi festival history occurred in 1699, when Guru Gobind Singh chose Vaisakhi as the day to establish the Khalsa. This act permanently altered the meaning of the festival.

Vaisakhi became:

- A symbol of equality and courage

- A declaration of collective responsibility

- A rejection of fear and injustice

By anchoring a spiritual revolution to a traditional harvest festival, Sikh leadership ensured that identity and daily life remained inseparable. Farming, faith, and freedom merged into a single narrative.

Festivals as Resistance Under Persecution

During periods of Mughal repression, festivals became subtle yet powerful acts of resistance. Gathering openly, sharing food, and remembering martyrs carried political significance.

In this era:

- Celebration affirmed survival

- Memory preserved truth

- Community protected continuity

Festivals were among the few spaces where Punjabi society could remain visible, united, and defiant without formal political power.

Martial Tradition and Collective Discipline

Some festivals, such as Hola Mohalla, were designed explicitly to reinforce:

- Physical preparedness

- Moral discipline

- Strategic unity

Mock battles, weapon displays, and martial arts were not glorifications of violence, but reminders that self-defense was a moral duty. Celebration, training, and remembrance blended seamlessly.

Martyrdom, Memory, and Moral Legacy

Over time, Punjabi festivals began to carry layers of historical memory. Martyrdom was not mourned in silence; it was remembered publicly, ensuring that sacrifice became part of communal identity rather than private grief.

This transformed festivals into:

- Living history lessons

- Moral anchors for future generations

- Collective acts of remembrance

A Distinct Punjabi Ethos Emerges

By the end of the Sikh era, Punjabi festivals had become unique in South Asia. They were:

- Rooted in land and labor

- Guided by ethical philosophy

- Strengthened by historical experience

Celebration did not distract from struggle—it validated it.

Colonial Rule, Partition, and the Transformation of Punjabi Festivals

The arrival of British colonial rule in the mid-19th century marked one of the most disruptive periods in Punjabi history. While colonial administration altered political power, land ownership, and economic systems, it also deeply affected cultural expression, including festivals. Punjabi celebrations, once organic and community-driven, were now forced to exist within an environment of bureaucracy, surveillance, and social restructuring.

Colonial Impact on Agrarian Life and Celebration

British land revenue systems transformed Punjab’s agrarian economy. Farming became more commercial, rigid schedules replaced seasonal intuition, and communal land practices weakened. As a result:

- Festivals lost some of their spontaneous, village-wide character

- Celebration periods shortened due to labor pressures

- Rituals were increasingly confined to private or symbolic spaces

Despite these pressures, Punjabi festivals did not disappear. Instead, they adapted quietly, becoming markers of cultural resistance rather than public defiance.

Festivals as Cultural Preservation Under Colonialism

Colonial authorities often viewed indigenous festivals as unproductive or backward. Yet for Punjabis, continuing these celebrations became an act of cultural preservation.

Festivals served to:

- Preserve language through folk songs

- Maintain oral history when formal education ignored local culture

- Sustain social bonds in rapidly changing rural structures

What could not be expressed politically was often expressed culturally—through music, food, and seasonal gathering.

The Trauma of Partition (1947)

The Partition of Punjab in 1947 was a civilizational rupture. Entire communities were uprooted, villages emptied, and centuries-old cultural continuities violently broken. Festivals, once tied to specific landscapes and shared neighborhoods, suddenly faced displacement.

In the aftermath:

- Many festivals were suspended due to grief and survival struggles

- Rituals lost geographic context but survived in memory

- Celebration shifted from public spaces to family units

Yet even in refugee camps and unfamiliar lands, Punjabis continued to mark festivals—often quietly, sometimes symbolically—because doing so affirmed identity in the face of loss.

Reinvention Across Borders

Partition divided Punjab geographically, but not culturally. On both sides of the border, Punjabi festivals were reinterpreted to suit new realities.

- In rural areas, festivals remained land-focused

- In urban settings, celebrations became condensed and symbolic

- In diaspora communities, festivals turned into identity anchors

This period transformed Punjabi festivals from purely seasonal events into emotional links to a lost homeland.

From Survival to Revival

By the late 20th century, as stability returned, festivals experienced revival. However, they were no longer exactly the same. Memory, loss, and migration had reshaped them.

Festivals now carried:

- Nostalgia alongside joy

- Remembrance alongside celebration

- Identity alongside tradition

They became bridges between what was lost and what endured.

Punjabi Festivals in the Modern World: Continuity, Change, and Global Identity

In the modern era, Punjabi festivals have entered a new phase—one shaped by urbanization, globalization, and migration. While the physical environment that once defined these celebrations has changed, their core spirit has remained remarkably intact. Punjabi festivals today exist simultaneously in villages, cities, and global diaspora communities, each context reshaping form but not essence.

Urbanization and Changing Forms

As Punjab urbanized, festivals adapted to tighter spaces and faster lifestyles. Courtyards replaced fields, symbolic fires replaced communal bonfires, and scheduled events replaced organic gatherings. Yet the purpose of festivals endured.

Modern adaptations include:

- Condensed celebrations centered around family

- Cultural programs replacing spontaneous folk gatherings

- Symbolic rituals standing in for agricultural practice

Despite these changes, festivals continue to function as pause points in modern life, moments to reconnect with ancestry, language, and shared memory.

Global Diaspora and Cultural Preservation

Punjabi migration across the world transformed festivals into powerful tools of cultural preservation. In countries far removed from Punjab’s rivers and fields, festivals became portable homelands.

For diaspora communities:

- Festivals teach younger generations identity and history

- Language, dress, and food become acts of remembrance

- Celebration becomes declaration: we are still Punjabi

Public festivals, parades, and cultural fairs have turned Punjabi celebrations into visible symbols of global multiculturalism.

Media, Commercialization, and Identity

Modern media has amplified Punjabi festivals, but also reshaped them. Music, cinema, and social platforms have popularized certain aspects—dance, fashion, spectacle—sometimes at the cost of depth.

Yet this visibility has also:

- Revived interest among youth

- Preserved folk music in new forms

- Extended reach beyond geography

The challenge of the modern age is balance: honoring tradition without freezing it, embracing change without losing meaning.

Why Punjabi Festivals Still Matter

In a world increasingly disconnected from land and labor, Punjabi festivals remain reminders of:

- Gratitude over entitlement

- Community over isolation

- Memory over amnesia

They insist that celebration must be earned, shared, and rooted in purpose.

Conclusion: Festivals as the Memory of a Civilization

Punjabi festivals are not relics of the past; they are living expressions of survival, adaptation, and continuity. They have endured climate, conquest, colonization, and displacement—because they belong to the people, not institutions.

Each bonfire, song, shared meal, and gathering carries centuries of meaning. Together, they tell the story of a civilization that chose resilience over erasure, community over division, and memory over forgetfulness.

To celebrate a Punjabi festival is to participate in history—not by looking backward, but by carrying it