The Architect of Algebra, Algorithms, and the Mathematical Language of the Modern World

Introduction

Among the giants of the Islamic Golden Age, few individuals have shaped the modern world as profoundly as Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi. Living in the 9th century, he was not merely a mathematician or astronomer; he was a system builder—a scholar who transformed abstract knowledge into practical tools that could be taught, replicated, and applied across civilizations.

Al-Khwarizmi represents a decisive turning point in human intellectual history: the moment when mathematics evolved from philosophical speculation into a universal, operational science. Every equation solved today, every computer program written, and every algorithm executed carries the imprint of his legacy.

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi was born around 780 CE in the region of Khwarizm (modern-day Khiva, Uzbekistan), a strategically important and intellectually active area of Central Asia. At the time of his birth, Khwarizm stood at the crossroads of Persian, Indian, and Central Asian civilizations, benefiting from centuries of scholarly exchange along the Silk Road. This multicultural environment played a decisive role in shaping his intellectual orientation.

Khwarizm was not a remote province; it was a center where astronomy, mathematics, calendrical science, and administrative accounting were already well developed due to the region’s needs in agriculture, trade, and governance. Scholars in Khwarizm were particularly skilled in numerical calculation, astronomical observation, and land measurement, disciplines that would later become central to Al-Khwarizmi’s work. Growing up in such an environment exposed him early to practical mathematics rather than purely abstract speculation.

Although detailed records of his family life do not survive, historical context strongly suggests that Al-Khwarizmi received a formal education typical of scholarly households. This would have included instruction in:

- arithmetic and geometry,

- Persian administrative mathematics,

- basic astronomy and calendrical systems,

- and the scientific traditions inherited from India and pre-Islamic Persia.

Importantly, Al-Khwarizmi’s early education coincided with a broader intellectual transformation in the Islamic world. The Abbasid Caliphate was actively encouraging scholarship, translation, and scientific inquiry. Knowledge from India and Greece was being sought, translated, and critically examined. This atmosphere ensured that young scholars were trained not merely to preserve inherited knowledge, but to analyze, refine, and expand it.

Al-Khwarizmi’s exposure to Indian numerical systems at an early stage was particularly significant. Khwarizm had longstanding connections with Indian scholars, and Indian mathematical texts had already begun circulating in the region before reaching Baghdad. This early familiarity later enabled him to play a central role in adapting and systematizing the Hindu numeral system for wider use.

His formative years were therefore marked by three defining characteristics:

- Practical mathematical orientation rooted in administration, trade, and astronomy

- Cross-cultural exposure to Persian, Indian, and emerging Islamic intellectual traditions

- A problem-solving mindset, shaped by real-world computational needs rather than philosophical abstraction

This background distinguished Al-Khwarizmi from earlier mathematicians. He was not trained as a speculative philosopher but as a scientific organizer, someone prepared to convert scattered knowledge into coherent systems.

By the time he reached early adulthood, his reputation as a gifted mathematician and astronomer had grown sufficiently to draw attention from Abbasid intellectual circles. This recognition eventually led him to Baghdad, where his early training would find its full expression at the House of Wisdom. There, the skills developed in Khwarizm—precision, calculation, and synthesis—would mature into innovations that reshaped global science.

In this sense, Al-Khwarizmi’s early life explains his later achievements. He did not invent algebra and algorithms in isolation; he emerged from a region and an educational culture already oriented toward applied science, numerical clarity, and systematic thinking. His genius lay in recognizing the universal potential of these methods and elevating them into formal disciplines that could serve all of humanity.

Education in Baghdad and Entry into the Abbasid Scientific World

Al-Khwarizmi’s move to Baghdad marked the decisive turning point in his intellectual development. By the early ninth century, Baghdad was not merely the political capital of the Abbasid Caliphate; it was the intellectual capital of the known world. Scholars from Persia, Central Asia, India, the Eastern Mediterranean, and beyond converged there under state patronage. This environment transformed individual talent into civilizational achievement.

Under the reign of Caliph al-Ma’mun, scholarship was elevated to a matter of state policy. Al-Ma’mun believed that political authority was strengthened by scientific knowledge, accurate administration, and rational governance. As a result, scholars were not only respected but financially supported, given access to libraries, instruments, and collaborative research spaces. Al-Khwarizmi entered this world at precisely the right historical moment.

At the heart of this intellectual ecosystem stood the Bayt al-Hikmah (House of Wisdom)—a unique institution combining features of a research institute, translation bureau, observatory, and academy. Al-Khwarizmi was appointed as a senior scholar there, a role that indicates not only his technical ability but also his capacity for synthesis and instruction.

His education in Baghdad differed fundamentally from earlier models of learning. Rather than studying under a single master or school, Al-Khwarizmi was immersed in a multidisciplinary research culture. He worked alongside:

- mathematicians refining Greek geometry,

- astronomers adapting Indian and Persian tables,

- translators rendering scientific texts into Arabic,

- geographers compiling empirical data from travelers and administrators.

This collaborative environment shaped his intellectual character. He learned not simply to inherit knowledge, but to organize it, compare it, test it, and reformulate it for practical use.

A critical aspect of his Baghdad education was direct exposure to Indian mathematical astronomy. Indian texts introduced advanced numerical techniques, positional notation, and efficient calculation methods. Al-Khwarizmi recognized immediately that these tools were superior to older Greek and Roman systems for administrative and scientific purposes. His genius lay in adapting these techniques into a universal, teachable framework compatible with Islamic legal, economic, and scientific needs.

Equally important was his engagement with Greek scientific traditions, particularly works attributed to Euclid and Ptolemy. Unlike later European scholastics who often treated Greek authorities as unquestionable, Al-Khwarizmi approached them critically. Greek geometry provided theoretical rigor, but it lacked computational efficiency. Al-Khwarizmi bridged this gap by combining Greek structure with Indian numerical power.

His education in Baghdad thus produced a scholar with three defining competencies:

- Theoretical literacy in Greek mathematics and astronomy

- Computational mastery rooted in Indian numerical systems

- Administrative and practical orientation shaped by Abbasid governance needs

This combination was unprecedented. It allowed Al-Khwarizmi to see mathematics not as an abstract philosophical exercise, but as a toolkit for civilization—capable of solving legal disputes, managing state finances, organizing land surveys, supporting astronomy, and standardizing knowledge.

By the time he began writing his major works, Al-Khwarizmi was no longer simply a student or translator. He had become a system architect—a scholar trained to convert diverse intellectual traditions into unified scientific disciplines. His education in Baghdad did not merely expand his knowledge; it reshaped his purpose. He now sought to create methods that others could learn, apply, and extend long after his lifetime.

This educational foundation explains why his later contributions—algebra, algorithms, and numerical systems—were not isolated discoveries, but structured sciences. Baghdad gave Al-Khwarizmi the environment necessary to transform personal brilliance into global intellectual infrastructure.

Major Works and Intellectual Methodology: How Al-Khwarizmi Built Teachable Sciences

Al-Khwarizmi’s enduring significance lies not only in what he discovered, but in how he structured knowledge. His intellectual methodology marked a decisive break from earlier traditions of learning. Where previous scholars often presented mathematics and science as elite, abstract, or philosophically dense disciplines, Al-Khwarizmi deliberately designed his works to be clear, systematic, and teachable. His goal was not to impress specialists, but to equip society with reliable scientific tools.

This methodological clarity is most evident in his major works, each of which addressed a practical need of Islamic civilization—law, administration, astronomy, geography, and education.

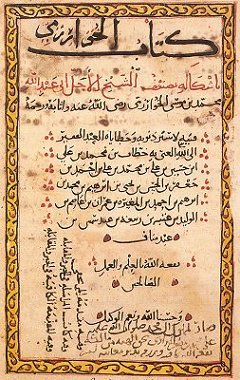

Al-Jabr wa’l-Muqabala: Structuring Algebra as a Science

In Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wa’l-Muqabala, Al-Khwarizmi did something unprecedented: he transformed scattered mathematical techniques into a coherent discipline with defined rules. Instead of solving isolated problems, he classified equations into standard forms and demonstrated general methods to solve them. This abstraction allowed mathematics to move beyond geometry and become a universal problem-solving language.

Equally important was his pedagogical intent. He wrote in plain, accessible prose and grounded his explanations in real-world scenarios such as:

- inheritance distribution under Islamic law,

- commercial transactions,

- land measurement,

- and construction planning.

By embedding algebra within everyday needs, he ensured its widespread adoption. Mathematics was no longer confined to scholars—it became an essential civic skill.

Arithmetic and the Logic of Algorithms

In his writings on arithmetic, Al-Khwarizmi introduced step-by-step procedures for calculation using the decimal system. These procedures were finite, repeatable, and independent of intuition. This approach represents one of the earliest formalizations of algorithmic thinking.

His method had three defining characteristics:

- Each problem was broken into discrete steps

- Each step followed a fixed rule

- The process always produced a predictable result

This logic allowed calculation to be taught mechanically, enabling large bureaucracies, traders, and scientists to perform complex operations with accuracy. In effect, Al-Khwarizmi converted mathematical reasoning into a technology of thought—a development that would later underpin computer science.

Astronomy and Standardization of Measurement

In astronomy, Al-Khwarizmi’s Zij al-Sindhind exemplified his method of scientific synthesis. Rather than copying Indian or Greek tables, he:

- compared multiple sources,

- corrected inconsistencies,

- standardized measurements,

- and adapted data for practical use in the Islamic world.

His astronomical tables were designed for function, not speculation. They enabled precise calendar calculations, prayer time determination, and astronomical observation—demonstrating his consistent focus on usability.

Geography and Empirical Organization of Space

Al-Khwarizmi’s geographical work further illustrates his methodological discipline. Revising earlier maps, he corrected coordinate errors and presented geographic knowledge in a structured format that could support administration, trade, and travel. This was geography as applied science—data organized for decision-making, not mere description.

A Unified Intellectual Method

Across all disciplines, Al-Khwarizmi applied the same intellectual principles:

- classification over confusion,

- method over intuition,

- clarity over complexity,

- application over abstraction.

This consistency reveals his deeper contribution: he invented a model of scientific writing and teaching. Knowledge became cumulative because it was standardized. Science became transferable because it was methodical. Education became scalable because it was systematic.

In this sense, Al-Khwarizmi did not simply contribute to mathematics, astronomy, or geography individually. He redefined what it meant to produce scientific knowledge. His works established a template that later scholars—both in the Muslim world and in Europe—would follow for centuries.

By transforming science into a structured, teachable system, Al-Khwarizmi ensured that knowledge could outlive individuals and travel across civilizations. This methodological breakthrough explains why his influence did not fade with time but expanded, shaping the intellectual foundations of the modern world.

Transmission to Europe and Global Legacy: How Al-Khwarizmi Shaped the Modern World

Al-Khwarizmi’s influence did not end with the Abbasid Caliphate. On the contrary, his greatest historical impact began after his works crossed linguistic and cultural borders, becoming foundational texts for the rise of European science. The transmission of his ideas from the Islamic world to Latin Europe represents one of the most important intellectual migrations in human history.

From the 12th century onward, European scholars in translation centers such as Toledo, Sicily, and southern Italy encountered Al-Khwarizmi’s writings through Arabic–Latin translations. His name appeared in Latinized form as Algoritmi, and his books rapidly became standard texts in emerging European schools. At a time when Europe lacked a unified mathematical system, Al-Khwarizmi’s structured approach offered exactly what was missing: clarity, method, and reliability.

Algebra Enters Europe

When Al-Jabr wa’l-Muqabala was translated into Latin, it introduced Europe to an entirely new way of thinking about mathematics. Prior to this, European mathematics relied heavily on Roman numerals and geometric reasoning, which severely limited calculation and abstraction. Al-Khwarizmi’s algebraic methods enabled:

- general equation solving,

- symbolic reasoning,

- and numerical abstraction independent of geometry.

This transformation directly influenced medieval European mathematics and later figures of the Renaissance. Algebra became a central discipline in universities, eventually leading to advances in physics, engineering, and economics.

Algorithms and the Mechanization of Thought

Equally transformative was the adoption of Al-Khwarizmi’s algorithmic methods. His step-by-step approach to calculation introduced a new intellectual discipline: procedural reasoning. European scholars began using the term algorismus to describe arithmetic operations performed according to fixed rules.

This concept fundamentally changed how problems were approached. Knowledge was no longer dependent on intuition or personal genius; it could be executed mechanically. This intellectual shift laid the groundwork for:

- modern bookkeeping,

- navigation and engineering calculations,

- mathematical modeling,

- and eventually computer programming.

The logic underlying modern computing—clear instructions executed in sequence—can be traced directly to this methodological legacy.

Numerical Revolution and the End of Roman Numerals

Perhaps Al-Khwarizmi’s most practical legacy was the spread of the decimal positional number system. As his arithmetic works circulated, European scholars gradually abandoned Roman numerals in favor of Hindu-Arabic numerals. This change revolutionized:

- commerce,

- taxation,

- engineering,

- astronomy,

- and scientific experimentation.

The ability to perform complex calculations efficiently accelerated every field of knowledge. Modern mathematics, physics, and finance would be inconceivable without this numerical transformation.

Long-Term Civilizational Impact

By the time Europe entered the Renaissance, much of its scientific infrastructure—mathematics, astronomy, navigation, and accounting—was already shaped by Al-Khwarizmi’s intellectual framework. His influence extended indirectly to:

- Copernican astronomy,

- Renaissance engineering,

- early modern physics,

- and the rise of scientific academies.

Yet his role was often obscured as his ideas were absorbed into European tradition without acknowledgment of their Islamic origin. Algebra remained Arabic in name, but its origins were increasingly forgotten.

Why Al-Khwarizmi Remains Central Today

Al-Khwarizmi’s legacy is not confined to history textbooks. His intellectual architecture continues to operate invisibly beneath modern civilization. Every digital device, every engineering model, every economic forecast, and every scientific simulation depends on:

- algebraic abstraction,

- algorithmic logic,

- and decimal computation.

He represents a rare historical figure whose work transcended time, culture, and language to become structural knowledge—knowledge so fundamental that it disappears into everyday life.

Final Assessment

Al-Khwarizmi was not simply a mathematician of the Islamic Golden Age; he was a civilizational engineer. He transformed knowledge into systems, ideas into tools, and thought into infrastructure. By doing so, he ensured that science could grow beyond individuals and become a permanent feature of human progress.

His work exemplifies the true spirit of the Golden Age of Islam:

the transformation of philosophy into practical science, and knowledge into universal benefit.

Conclusion – Al-Khwarizmi and the Architecture of Modern Knowledge

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi stands as one of the most consequential figures in the history of human knowledge, not because he merely contributed to existing sciences, but because he restructured how knowledge itself was produced, taught, and applied. At a critical moment in world history, when civilizations possessed fragments of mathematical and scientific insight but lacked unifying systems, Al-Khwarizmi provided the intellectual architecture that transformed scattered ideas into operational disciplines.

His greatest achievement was the elevation of mathematics from abstract reasoning to a practical, universal language of problem-solving. By founding algebra as an independent science, formalizing algorithmic procedures, and standardizing numerical computation, he enabled knowledge to become scalable, transferable, and cumulative. These qualities are the defining characteristics of modern science and technology.

Equally important was his methodological legacy. Al-Khwarizmi demonstrated that science advances not through speculation alone, but through classification, clarity, verification, and application. His works were designed to be taught, replicated, and expanded—ensuring that scientific progress did not depend on individual genius, but on structured systems accessible to society at large. In doing so, he transformed scholarship into infrastructure.

The global transmission of his ideas reshaped civilizations far beyond the Islamic world. European mathematics, Renaissance science, modern engineering, and contemporary computing all developed upon foundations that Al-Khwarizmi helped establish. Yet his contributions are so deeply embedded in modern life that they are often taken for granted, their origins forgotten even as their influence remains omnipresent.

Al-Khwarizmi therefore represents more than a historical figure; he represents a civilizational turning point. He embodies the moment when the Islamic Golden Age converted intellectual vision into practical science and when human reasoning acquired tools capable of shaping the modern world.

In the story of global scientific development, Al-Khwarizmi is not a supporting character—he is one of its principal architects. His legacy affirms a central truth of history: modern civilization did not emerge in isolation, but was built through the systematic contributions of Muslim scholars whose work continues to define the structure of knowledge itself.