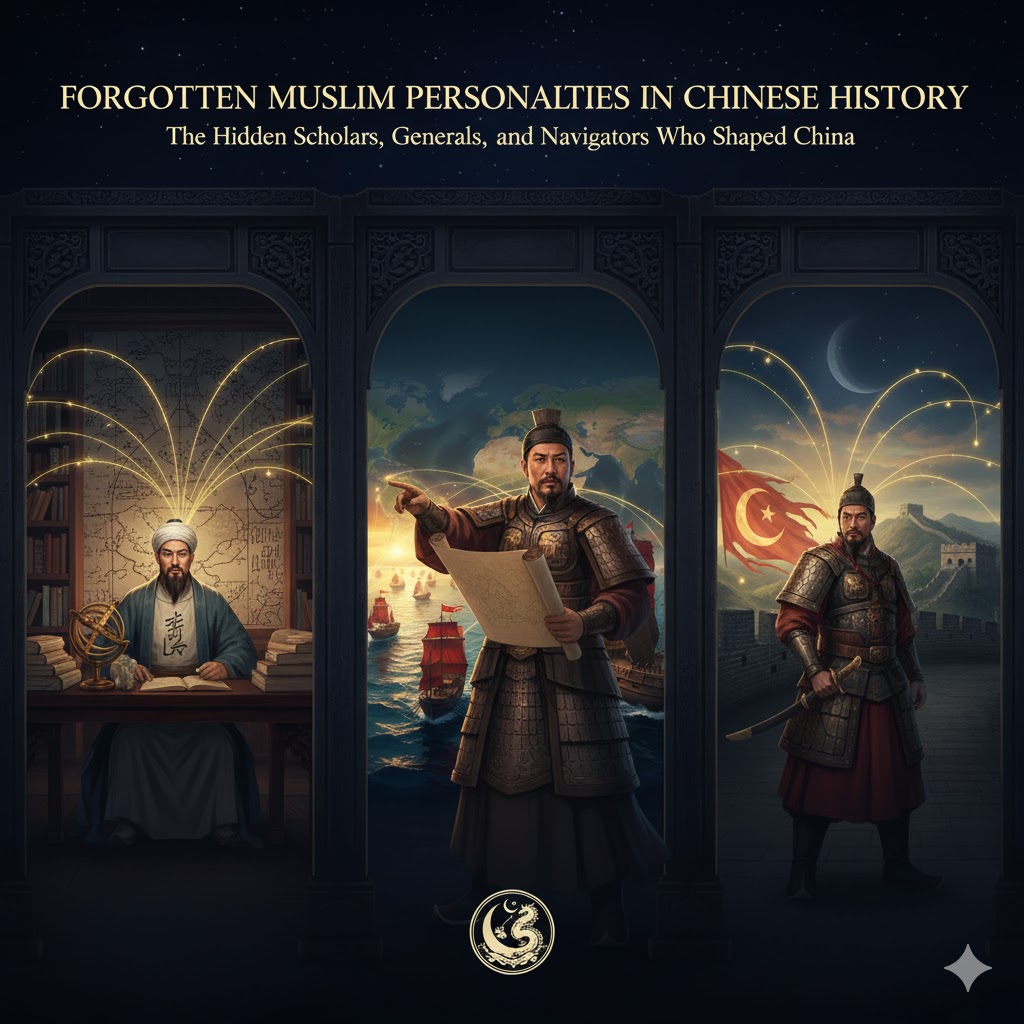

Across the vast canvas of Chinese history, stretching over five thousand years, countless dynasties have risen and fallen like waves on an endless sea. Emperors carved their legacies into stone, scholars inked philosophy onto bamboo, and warriors defended the frontiers with unwavering loyalty.

Yet hidden beneath the grandeur of these chronicles lies a forgotten truth — that Muslims played a profound and enduring role in shaping Chinese civilization.

From the bustling ports of Guangzhou where Arab traders first dropped anchor in the Tang dynasty, to the imperial courts of the Ming where Muslim generals and astronomers advised emperors, the story of Islam in China is not one of separation — but of integration, contribution, and quiet brilliance.

These Muslims were not outsiders looking in.

They were:

- Advisors to emperors,

- Founders of cities,

- Generals who won dynasties,

- Navigators who mapped oceans,

- Scholars who fused Confucian ethics with Islamic theology,

- Philosophers who translated divine truth into the rhythm of Chinese wisdom.

They built mosques that looked like temples, wrote Arabic in elegant Chinese calligraphy, and preserved their faith while serving under the Dragon Throne with honor.

Their names once echoed through the palaces of Beijing, the observatories of Kaifeng, the markets of Xi’an, and the shipyards of Nanjing — yet today, they have faded from the world’s collective memory.

🌙 A Story Lost Between Two Civilizations

When people speak of Islamic history, they speak of Baghdad, Cairo, Cordoba, Samarkand — but rarely Beijing or Nanjing.

When people speak of Chinese history, they speak of Confucius, Qin Shi Huang, or Emperor Yongle — but rarely Ma Yize, Chang Yuchun, or Liu Zhi.

And yet, these forgotten personalities stood at the crossroads of two great civilizations.

Their lives proved that Islam could flourish under a Confucian empire, and that the Middle Kingdom could grow stronger through the contributions of its Muslim citizens.

🌏 Why Their Stories Matter Today

In a world divided by misconceptions about identity, faith, and culture, the Muslim history of China stands as a living testament to coexistence.

It shows that diversity is not a weakness—but a force that expands a civilization’s horizons.

These Muslims:

- revolutionized Chinese astronomy,

- shaped imperial military strategy,

- built the foundations of Islamic thought in Chinese language,

- and connected China to Arabia, India, and Africa long before the age of European exploration.

Their stories reveal a past where civilizations met not through conquest, but through trade, diplomacy, science, and shared curiosity.

🌠 Rediscovering the Crescent in the East

This article resurrects ten of the most extraordinary — yet largely forgotten — Muslim personalities in Chinese history.

Their biographies read like epics: warriors who never lost, scholars who wrote bridges between religions, navigators who taught China the science of the sea, philosophers who harmonized reason and revelation.

By reviving their memories, we revive a chapter of history that belongs not just to China or the Muslim world, but to all humanity.

These are the lost stars of the Middle Kingdom.

Stars that once guided emperors, explorers, and entire civilizations — now shining again.

🧭 1. Ma Yize (馬依澤) – The First Muslim Astronomer of China

Dynasty: Song (10th–11th century CE)

Origin: Arabian descent, based in Kaifeng

When the Song Dynasty emerged in 960 CE, China stood at a turning point. Trade across the Silk Road was thriving, foreign merchants filled the ports of Guangzhou and Quanzhou, and scientific ideas flowed more freely than ever before.

Into this landscape arrived a man whose knowledge of the stars would forever change Chinese astronomy — Ma Yize, the first officially recorded Muslim astronomer in Chinese history.

His contribution marked the beginning of a scientific collaboration between Islamic astronomy and Chinese cosmology, creating a fusion that would guide calendars, navigation, and imperial rituals for centuries.

🌙 Origins and Arrival at the Song Court

Ma Yize’s family was of Arab or Persian descent, likely connected to the scientific centers of Baghdad or Bukhara — cities renowned for mathematical astronomy and translation schools.

His ancestors were part of the merchant-scholar networks that traveled to China during the Tang and early Song, bringing with them:

- star charts,

- astronomical tables (zij),

- advanced geometry,

- and knowledge of celestial motion inherited from scholars like Al-Battani, Al-Farghani, and Al-Khwarizmi.

By the early Song Dynasty, Ma Yize had gained recognition for his mastery of Islamic mathematical astronomy, a discipline far more sophisticated than China’s then-traditional methods.

Impressed by his expertise, Emperor Taizu of Song invited him to the imperial court in Kaifeng.

This moment marked the first official integration of Islamic astronomy into Chinese state science.

🔭 Revolutionizing Chinese Astronomy

Before Ma Yize, Chinese astronomy focused heavily on:

- the five phases (wood, fire, earth, metal, water),

- yin-yang cosmology,

- and the movement of the sun and moon across the 28 lunar mansions.

While accurate in cultural interpretation, the system had limitations in predicting eclipses, calculating planetary motion, and creating long-term calendars.

Ma Yize introduced new mathematical methods that transformed the field.

His Contributions Included:

1. The Adoption of Islamic Astronomical Tables (Zīj)

He introduced translated versions of:

- Al-Zīj al-Sindhind, based on Indian and Islamic models,

- Al-Battani’s planetary tables,

- and Persian trigonometric star charts.

These tables allowed precise calculations of:

- eclipse prediction,

- solar longitude,

- lunar apogee,

- planetary retrograde motion.

This was far beyond what Chinese models of the time could achieve.

2. Trigonometric Astronomy

Islamic astronomers had developed spherical trigonometry, including:

- sine law,

- tangent models,

- and angular measurements used for qibla calculation.

Ma Yize incorporated this into Chinese astronomy — a breakthrough that improved:

- nautical navigation,

- calendar accuracy,

- and imperial weather predictions.

3. The “Yingtian Calendar” (應天曆)

In 963 CE, Ma Yize worked with Song scholar Wang Chuna to create the Yingtianli, a revolutionary new calendar system that replaced older Tang-era charts.

Its improvements included:

- more precise solar cycles,

- corrected lunar months,

- accurate eclipse forecasting,

- integration of Islamic star mathematics.

This became the official calendar of the Song Empire, used for:

- agriculture,

- taxation cycles,

- astrology,

- imperial rituals.

Ma Yize’s name was permanently recorded in the official court annals for this achievement.

🌍 Master of Cross-Civilizational Science

Ma Yize was not just an astronomer — he was a translator of worlds.

He understood that Chinese cosmology was rooted in harmony, balance, and symbolism, whereas Islamic astronomy was based on:

- empirical observation,

- mathematical precision,

- and geometric modeling.

By merging the two, he created a hybrid scientific tradition that would shape China’s intellectual life for centuries.

He demonstrated that:

- Science is universal.

- Knowledge can cross borders.

- Faith and reason can coexist without conflict.

His work also connected China to the broader Islamic Golden Age, at a time when the Muslim world was the global center of scientific innovation.

📜 Court Titles and Recognition

Seeing his brilliance, Emperor Taizu appointed Ma Yize as:

- Chief Astronomical Officer,

- Assistant Director of the Court Observatory,

- and later as a senior advisor on scientific matters.

He held one of the highest scientific ranks available to foreigners in Chinese history.

The emperor granted him:

- a mansion in Kaifeng,

- a hereditary court position for his descendants,

- and high honor among bureaucrats and scholars.

This signaled the Song dynasty’s formal acceptance of Islamic science as part of Chinese statecraft.

🌠 Legacy – The Star Bridge Between Islam and China

Ma Yize’s influence extended far beyond his lifetime.

His Legacy Includes:

- Establishing Islamic astronomy as a respected discipline in China.

- Paving the way for the Islamic Astronomical Bureau in the Yuan and Ming dynasties.

- Influencing later Muslim scholars like Jamāl al-Dīn, Guo Shoujing, and the navigators of Zheng He’s fleets.

- Helping China eventually develop some of the world’s most advanced astronomical instruments.

His methods shaped imperial calendars for 400+ years.

His descendants served the Song court for seven generations, continuing his work in astronomy and mathematics.

Though not widely known today, Ma Yize was one of the founding architects of scientific exchange between China and the Muslim world.

✨ Why Ma Yize Matters Today

His life reminds us that:

- History is multicultural.

- Science belongs to no single civilization.

- Muslims were not just visitors to China — they were shapers of its intellectual tradition.

Ma Yize stands as one of the earliest symbols of:

- cross-cultural harmony,

- scientific cooperation,

- and the universal human desire to understand the stars.

“He aligned the skies of Islam with the heavens of China, and the two shone brighter for it.”

⚔️ 2. Chang Yuchun (常遇春) – The Muslim General Who Founded the Ming Dynasty

Dynasty: Early Ming (14th century CE)

Origin: Hui Muslim from Anhui

In the chaotic twilight of the Yuan Dynasty, when warlords carved territories with blood and famine swept the land, a young Hui Muslim warrior rose from obscurity to become one of the most formidable generals in Chinese history.

His name was Chang Yuchun, and he would become the blazing sword that cleared the path for the birth of the Ming Dynasty.

Chang Yuchun’s story is one of loyalty, courage, faith, and military genius, yet his name rarely appears in global history — despite being as influential in China’s founding as Khalid ibn al-Walid was in early Islamic history.

🌙 Humble Muslim Origins

Chang Yuchun was born in 1328 in Huaibei, Anhui Province, into a poor Hui Muslim family.

Life in the waning years of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty was harsh:

- heavy taxes crushed farmers,

- famine ravaged the countryside,

- and corruption spread like wildfire.

Yet, from this difficult childhood emerged a boy known for:

- extraordinary strength,

- fearlessness,

- deep compassion for the oppressed,

- and strong Islamic values of justice and humility.

He grew up reciting Qur’anic teachings and Confucian moral sayings — a blend that shaped both his battlefield ethics and leadership style.

⚔️ Joining the Red Turban Rebellion – Rise of a Warrior

As the Yuan government collapsed, rebellions erupted across the empire.

Chang Yuchun joined one such uprising, led by Zhu Yuanzhang, who would later become Emperor Hongwu, founder of the Ming Dynasty.

From the moment they met, Zhu Yuanzhang recognized Chang Yuchun’s potential:

- unmatched physical strength,

- tactical brilliance,

- ability to inspire soldiers,

- and personal piety that commanded respect.

Chang’s rise was meteoric.

He went from a common soldier to one of the most trusted generals in Zhu’s inner circle — earning the nickname:

“Chang the Fearless” (常无畏)

⚔️ Military Genius – A General Who Never Lost a Battle

Chang Yuchun quickly became the Ming army’s sharpest blade.

He led decisive campaigns against rival warlords and Mongol forces.

Chinese historical records note that Chang Yuchun’s marches were swift, his strategies unpredictable, and his victories overwhelming.

His greatest achievements include:

1. The Victory at Lake Poyang (1363)

One of the largest naval battles in world history.

Chang Yuchun played a critical role in defeating Chen Youliang, a powerful rival warlord.

This victory cleared the path for Zhu Yuanzhang to unify southern China.

2. The Conquest of Northern China

Chang led the Ming armies to seize vital cities:

- Dadu (Beijing),

- Shanxi,

- Ningxia,

- and the Great Wall regions.

He defeated Mongol generals who had ruled these lands for nearly a century.

3. Pursuit of the Mongols Beyond the Great Wall

Chang Yuchun didn’t stop at reclaiming China.

He chased fleeing Mongol forces into the steppe, securing the northern frontier and earning the reputation of a warrior “feared by the Mongols themselves.”

Historical accounts describe him as:

“A man whose charge was like thunder and whose presence broke enemy morale.”

He never wavered, never retreated — a general undefeated in every campaign.

🤝 Loyalty and Compassion – A Warrior of Faith

Despite his fearsome battlefield reputation, Chang Yuchun was known for his kindness and strict morality.

Muslim historians and Chinese sources alike note that he:

- never killed civilians,

- forbade looting,

- protected the poor,

- prayed regularly,

- and encouraged soldiers to act with discipline and justice.

His character reflected Islamic values of mercy, integrity, and service to humanity.

Zhu Yuanzhang often said:

“Among all my generals, none is as loyal, brave, and pure-hearted as Chang Yuchun.”

🏛️ A Founder of the Ming Dynasty

When Zhu Yuanzhang declared himself Emperor Hongwu in 1368, he acknowledged that his victory was due in large part to Chang Yuchun.

He rewarded Chang with:

- high military titles,

- vast land grants,

- and the prestigious rank of Duke of Wei (魏国公).

Though Chang died shortly after the founding of the Ming (in 1369 at age 41), the emperor honored him with an exquisite tomb and posthumous titles.

Hongwu even said:

“If Chang Yuchun had lived longer, he would have been the pillar of my empire.”

His descendants continued to serve the court with honor for generations.

🌠 Legacy – The Muslim General Who Forged a Dynasty

Chang Yuchun is remembered as:

- one of the greatest military minds of Chinese history,

- a founder of the Ming Dynasty,

- a symbol of Muslim loyalty and heroism,

- and a unifying force during China’s most chaotic era.

His life disproves the myth that Muslims were marginal in Chinese history.

He stands tall among the founders of the Ming, equal to Zhu Yuanzhang’s most iconic generals.

Why Chang Yuchun is Forgotten Today

Despite his greatness, he faded from memory due to:

- political suppression after his death,

- anti-Muslim policies by later emperors,

- and centuries of rewriting history through Han-centric lenses.

Yet modern historians now recognize him as:

one of the most important Muslim figures to ever shape China’s destiny.

🧭 Chang Yuchun in One Line

“A Muslim warrior whose sword carved the path of a dynasty,

and whose heart upheld justice in the darkest of times.”

🌙 3. Lan Yu (藍玉) – Duke of Liang and Defender of the Realm

Dynasty: Early Ming (14th–15th century CE)

Origin: Hui Muslim from Yunnan

If Chang Yuchun was the sword that carved the Ming Dynasty, then Lan Yu was the hammer that solidified its walls.

Bold, brilliant, sometimes ruthless, and deeply loyal to his emperor, Lan Yu was a Hui Muslim general whose military genius reshaped China’s northern frontier and broke the power of the Mongols once and for all.

Though history often remembers monarchs and philosophers, few recall the Muslim general whose campaigns ensured the Ming Dynasty’s security for decades.

Lan Yu’s story is one of ambition, loyalty, victory, and a tragic fall — a warrior celebrated in his lifetime yet almost erased from the history that followed.

🌙 Early Life – A Muslim Warrior from Yunnan

Lan Yu was born in Yunnan Province, home to one of China’s largest Hui Muslim communities.

Yunnan at the time was a frontier of multiple cultures — Chinese, Mongol, Tibetan, Southeast Asian — and Islam had deep roots there since the Yuan era.

From a young age, Lan Yu:

- trained in horseback combat,

- mastered the bow,

- practiced military discipline,

- and was known for his fiery courage.

His Islamic upbringing instilled in him:

- justice,

- loyalty,

- honesty,

- and the warrior ethos of protecting the weak.

Lan Yu entered military service during the rise of Zhu Yuanzhang (later Emperor Hongwu), at a time when China was fractured among rebel factions, warlords, and Mongol armies.

⚔️ Rise Through the Ranks – The Emperor’s Relentless Blade

Lan Yu’s rise was nothing short of meteoric.

His tactical brilliance and fearless battlefield presence quickly earned him a place among Hongwu’s elite commanders.

He participated in numerous campaigns that unified China under the Ming banner.

Hongwu trusted him with missions requiring:

- rapid action,

- high-level strategy,

- and unwavering loyalty.

Lan Yu became known as:

“the general who struck like lightning.”

His campaigns were often decisive — ending rebellions swiftly and securing key strongholds.

🐎 The Mongol Campaign – Lan Yu’s Greatest Triumph

🔥 Defeating the Northern Yuan

After the Ming Dynasty was established, remnants of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty retreated north beyond the Great Wall.

They continued to raid northern China, threatening the young Ming state.

In 1388, Emperor Hongwu entrusted Lan Yu with the most important mission of his career:

destroy the Mongol forces once and for all.

Lan Yu led:

- 150,000 elite cavalry and infantry,

- supported by scouts, engineers, and logistics units.

His speed and precision shocked even the Mongols — masters of steppe warfare.

⚔️ The Battle of Buir Lake (Buir Nor)

This was the decisive engagement.

Lan Yu:

- outmaneuvered Mongol horsemen,

- encircled their camps,

- captured or killed thousands,

- and forced the Mongol khan, Tögüs Temür, to flee into the wilderness.

It was one of the greatest victories in Ming military history.

Lan Yu had done what seemed impossible — he broke the military backbone of the Northern Yuan, ending a century-long threat to China.

For this, Emperor Hongwu rewarded him with the title:

Duke of Liang (梁国公)

A title reserved for the most honored military heroes.

⚖️ Lan Yu’s Leadership Style – Strict but Just

Lan Yu was known for his combination of:

- strict discipline,

- moral principles from his Islamic upbringing,

- and deep loyalty to the Ming throne.

He was respected and feared — but never hated — by his soldiers.

Chroniclers described him as:

“A man who punished injustice but protected the innocent,

and who treated the army as his family.”

His battlefield ethics were similar to Islamic principles of warfare:

- Do not harm civilians

- Do not destroy crops

- Do not mistreat captives

- Maintain discipline and honor

This reputation earned him the loyalty of troops and the respect of even his enemies.

🕌 Lan Yu’s Muslim Identity

Lan Yu’s Hui Muslim identity was well-known at court.

He prayed, maintained Islamic dietary laws, and supported Muslim communities in Yunnan and northern China.

He represented a rare integration of:

- Islamic ethics,

- Chinese loyalty,

- military excellence,

- and multicultural diplomacy.

In Lan Yu, we see the deep influence of Muslims in shaping early Ming power.

⚰️ The Tragedy – Fall from Power

Despite his brilliance, Lan Yu’s rising influence created enemies in the Ming court.

⚖️ The 1389–1393 Political Climate

After decades of war, Emperor Hongwu became increasingly suspicious and harsh with powerful officials.

Dozens of generals and ministers were executed in the “Hu Weiyong Case”, a period of paranoia and purges.

Lan Yu’s military popularity made him a target for jealous courtiers.

🗡️ The Charge of Treason

In 1393, the emperor accused Lan Yu of plotting rebellion — a charge historians believe was politically motivated, not based on evidence.

Lan Yu and hundreds of associates were executed.

The emperor later regretted the severity of the purge, but the damage was done.

China lost one of its most brilliant military minds.

🌠 Legacy – The General Who Secured the Ming Frontier

Despite his tragic end, Lan Yu remains one of the most important military figures in Chinese history, especially among Hui Muslims.

His legacy includes:

- Breaking Mongol power in the north

- Securing China’s borders for decades

- Serving with unmatched loyalty

- Showing that Muslims were central to the rise of the Ming Dynasty

- Earning one of the highest aristocratic titles granted to a general

Chinese historians acknowledge that without Lan Yu’s victories, the Ming Dynasty could have fallen early to Mongol resurgence.

Modern scholars see him as:

“The Muslim general who ensured China’s new dynasty lived long enough to flourish.”

Even though later politics tried to erase his memory, his impact cannot be denied.

🧭 Lan Yu in One Line

“He smashed the Northern Yuan, defended the Middle Kingdom, and carved his name into the foundations of the Ming—only to be consumed by its palace politics.”

🕌 4. Ma Fu – The Philosopher of Faith and Reason

Dynasty: Ming (15th–16th century CE)

Origin: Nanjing, Hui community

In the intellectual heart of the Ming Dynasty, where scholars debated the nature of Heaven and emperors sought guidance through moral philosophy, one Muslim thinker quietly reshaped the spiritual landscape.

His name was Ma Fu, a Hui Muslim scholar from Nanjing, whose writings laid the groundwork for a uniquely Chinese expression of Islam — a synthesis of Qur’anic truth and Confucian ethics.

Though overshadowed by later giants like Wang Daiyu and Liu Zhi, Ma Fu represents the first early wave of Muslim scholars who sought to harmonize Islamic theology with Chinese intellectual tradition.

He was a bridge — a philosopher whose pen carried both the crescent and the Confucian brushstroke.

🌙 Origins in Nanjing – A Scholar of Two Civilizations

Ma Fu lived during the 15th–16th century Ming Dynasty, a period of cultural flourishing but also of strict Confucian orthodoxy.

Nanjing, the Ming capital before Beijing, was home to:

- vibrant Hui Muslim communities,

- imperial academies,

- Confucian scholars,

- Buddhist monks,

- and foreign envoys from Central Asia and Arabia.

Ma Fu grew up in this multicultural environment, shaped by:

- Islamic education in family-run jingtang (mosque schools),

- Confucian moral training,

- and exposure to bureaucratic scholarly culture.

This dual upbringing made him part of a unique class of intellectuals known as the Huiru (回儒) —

Muslim Confucian scholars who believed Islam and Confucianism were not rivals, but mirrors reflecting universal truth.

📚 Ma Fu’s Intellectual Mission – Harmony, Not Conflict

During the Ming era, Muslims faced both acceptance and pressure.

While emperors respected their contributions, Confucian elites often viewed Islam as a foreign doctrine.

Ma Fu recognized the challenge and set out on a philosophical mission:

To prove that Islam could be expressed through Confucian concepts without losing its essence.

He argued:

- Confucianism taught moral order (li),

- Islam taught divine order (shari‘ah),

- Both sought harmony in human conduct,

- Both believed in Heaven (Tian) as the source of truth.

His writings emphasized:

- monotheism expressed through Chinese metaphysics,

- moral discipline compatible with Confucian virtues,

- loyalty, honesty, and filial piety as Islamic values too.

Ma Fu’s approach was not defensive — it was confident.

He did not present Islam as foreign to China; he presented it as already part of China’s ethical fabric.

🕌 His Core Ideas – A Fusion of Ethics and Theology

Although many of Ma Fu’s works survive only in fragments quoted by later scholars, historians identify several groundbreaking ideas:

1. “Tian” (Heaven) and Allah Are One Source of Moral Order

Ma Fu taught that:

“Heaven commands righteousness, and the True Lord rewards it.”

He equated the Confucian “Mandate of Heaven” with the Islamic concept of divine command.

2. Confucian Virtues Are Embodied in Islamic Practice

He showed that:

- filial piety (xiao)

- benevolence (ren)

- righteousness (yi)

- sincerity (cheng)

- ritual propriety (li)

all exist within Islam, through Qur’anic ethics and prophetic character.

3. Islam Complements, Not Replaces, Chinese Culture

He argued Islam strengthens Chinese morality by rooting virtue in a transcendent, singular God, not just social harmony.

This was revolutionary.

4. The Muslim Scholar Is Both a Confucian Gentleman and a Servant of God

Ma Fu believed that a Muslim could:

- serve the emperor faithfully,

- uphold Confucian order,

- and still fulfill Islamic duties.

His philosophy gave Chinese Muslims cultural confidence in an era of ideological scrutiny.

🧠 Influence on Later Scholars

Though Ma Fu never achieved the fame of Ming generals or court officials, his influence on Islamic philosophy in China was immense.

He became one of the early architects of the Han Kitab tradition — the body of Islamic texts written in classical Chinese during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Scholars like:

- Wang Daiyu (王岱輿)

- Liu Zhi (劉智)

- Ma Zhu (馬注)

built their monumental works upon concepts Ma Fu first articulated.

He provided:

- the vocabulary,

- the metaphysical framework,

- and the intercultural logic

needed to express Islam in Chinese terms.

Without Ma Fu, later Muslim scholars might not have achieved the philosophical synthesis that allowed Islam to flourish peacefully within Chinese civilization for centuries.

🌠 Legacy – The Quiet Sage of the Crescent and Confucian Brush

Ma Fu may not have commanded armies like Chang Yuchun or led fleets like Zheng He, but his contribution was intellectual and spiritual, shaping the Muslim identity of China from within.

His legacy includes:

- establishing early harmony between Islam and Confucianism,

- empowering Chinese Muslims to maintain faith with dignity,

- influencing centuries of Islamic scholarship in China,

- and proving that different civilizations can share a common moral universe.

He was a philosopher who believed that wisdom is universal and that truth can speak many languages — Arabic, Persian, and Chinese included.

📜 Ma Fu in One Line

“He wrote the bridge on which Islam walked into the heart of Chinese civilization.”

📘 5. Wang Daiyu (王岱輿) – The First Great Theologian of Chinese Islam

Dynasty: Late Ming / Early Qing (17th century CE)

Origin: Nanjing

In the fading twilight of the Ming Dynasty, as China faced political turbulence and philosophical fragmentation, a Muslim scholar emerged whose pen would redefine the place of Islam in Chinese civilization.

His name was Wang Daiyu, and he became the first major theologian to express Islam through the refined literary language and philosophical concepts of classical Confucian China.

Wang Daiyu did not fight wars or lead armies. Instead, he fought misunderstanding — the gap between Islamic belief and Confucian worldview.

Through his writings, he made Islam intellectually accessible to non-Muslim scholars and spiritually empowering to Chinese Muslims, creating a legacy that continues to shape Islamic thought in China today.

🌙 Early Life – A Scholar Rooted in Two Traditions

Wang Daiyu was born around 1590 CE in Nanjing, the old capital of the Ming Dynasty and one of China’s greatest centers of Muslim culture.

His family were Hui Muslims of Persian or Central Asian ancestry, scholars who had lived in China for generations.

From youth, Wang Daiyu was immersed in:

- Islamic sciences (Qur’an, hadith, jurisprudence, theology),

- Arabic and Persian linguistics,

- Confucian philosophy,

- Classical Chinese literature,

- Neo-Confucian metaphysics.

He quickly proved to be a prodigy — equally comfortable reading the Qur’an and interpreting the Analects of Confucius.

This dual mastery allowed him to understand something that many of his contemporaries could not:

Islam and Confucianism were not incompatible — they simply spoke different philosophical languages.

📚 His Mission – Translate Islam Into the Chinese Intellectual World

In Ming China, Islam was respected socially but still seen by many Confucian scholars as foreign and poorly understood.

Wang Daiyu recognized that unless Islam could be expressed in the conceptual language of Chinese philosophy, it would remain marginalized intellectually.

Thus began his life’s mission:

to rewrite Islamic theology in elegant classical Chinese, using Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist terminology without compromising Islamic creed.

This was revolutionary — no Muslim before him had attempted such a synthesis with such precision and literary sophistication.

📘 Major Works – The Foundations of Chinese Islamic Theology

Wang Daiyu authored several influential texts that laid the foundation for the Han Kitab tradition (汉克塔布), the body of Islamic texts written in Chinese by Muslim scholars.

1. Zhengjiao Zhenquan (正教真诠) – “The Real Explanation of the True Teaching”

His magnum opus.

This book systematically explains:

- the nature of God (Zhenzhu 真主),

- prophecy,

- creation,

- ethics,

- spiritual purification,

- and the human soul.

He used Chinese metaphysics to define Islamic monotheism:

“There is One True Lord above Heaven and Earth,

the Root of all principles (li)

and the Source of all existence.”

This concept allowed Chinese scholars to understand Allah not as a foreign deity but as the ultimate Heaven (Tian) that Confucians revered.

2. Qingzhen Zhinan (清真指南) – “The Guide to Islam”

A practical manual on Islamic practice:

- prayer,

- fasting,

- charity,

- moral conduct,

- dietary laws.

It explained why Muslims worship the One God using Confucian moral logic rather than foreign terminology.

3. Xi Zhen Zhengda (希真正答) – “Precious Answers to Favored Questions”

A text addressing Confucian critics who misunderstood Islam.

Wang Daiyu responded with philosophical gentleness and intellectual clarity, showing harmony rather than conflict.

Through these works, he elevated Islam into a scholarly discourse compatible with Chinese intellectual tradition.

🔍 Philosophical Contributions – Harmony of Two Worlds

Wang Daiyu’s theories went far beyond translation — he created a full metaphysical framework that resonated deeply with both Muslims and Confucian scholars.

1. The Unity of True Principle (真理一元)

He taught that God (Zhenzhu) is the source of:

- all principles (li),

- all being (you),

- all moral order (dao).

He unified Confucian and Islamic metaphysics under one ultimate Truth.

2. The Human Soul as the Mirror of Heaven

He adopted Confucian ideas of self-cultivation and aligned them with Islamic purification (tazkiyah).

The purpose of life, he wrote, is:

“to polish the soul until it reflects the radiance of the True Lord.”

3. Prophethood Explained in Confucian Terms

He described Prophet Muhammad ﷺ as the:

- “Utmost Sage” (至圣)

equivalent in moral perfection to Confucius, but bringing a divinely revealed Law.

4. Islam as the Completion of Universal Wisdom

He argued that all civilizations seek truth, but Islam completes it with revelation.

His ideas gave Chinese Muslims a sense of dignity and intellectual legitimacy in the greater cultural sphere of China.

🕌 Impact on Muslim Identity in China

Wang Daiyu’s influence was immense and long-lasting.

He helped Chinese Muslims:

- preserve their faith with cultural confidence,

- understand Islam in philosophical language familiar to Chinese society,

- dialogue respectfully with Confucian scholars,

- adapt without assimilating,

- feel Islam was not foreign but universally true.

He became the first pillar of the Chinese Islamic intellectual tradition.

💡 Influence on Later Generations

Wang Daiyu paved the way for:

- Liu Zhi (劉智) – the greatest Chinese Muslim philosopher,

- Ma Zhu (馬注) – scholar of Islamic orthodoxy,

- the entire Han Kitab tradition,

- the academic structure of mosque education (jingtang),

- interfaith dialogue between Islam and Confucianism.

Every major Islamic thinker in China after him built upon his foundations.

🌠 Legacy – The Scholar Who Made Islam Chinese

Wang Daiyu’s brilliance was his ability to show that:

- Islam is universal,

- Truth is harmonious,

- Different civilizations can reflect the same divine light.

His writings remain studied by scholars today in China, Central Asia, and the West.

He is remembered as:

“The first great interpreter of Islam in the Chinese tongue.”

And as the bridge that allowed millions of Chinese Muslims to understand their faith through the cultural lens of their homeland.

📘 Wang Daiyu in One Line

“He translated Islam into the heart-language of China, making foreign truth feel native without losing its divine core.”

🧠 6. Liu Zhi (劉智) – The Sage of the Han Kitab

Dynasty: Qing (18th century CE)

Origin: Nanjing

If Wang Daiyu laid the foundation of Islamic theology in Chinese, then Liu Zhi built the towering structure that stands to this day.

He is often called the Ibn Sina of China, the Ghazali of the East, and the bridge of wisdom between Islam and Confucianism.

His writings — elegant, philosophical, and profoundly mystical — remain the highest achievement of Islamic scholarship ever produced in the Chinese language.

Living during the culturally vibrant Qing Dynasty (17th–18th century CE), Liu Zhi elevated Islam from a community faith to a universal philosophy that harmonized with the deepest layers of Chinese intellectual tradition.

🌙 Early Life – A Scholar Born Between Two Worlds

Liu Zhi was born around 1660 CE in Nanjing, a major center of Hui Muslim culture and education.

He came from a respected Muslim family known for producing scholars and imams. His father ensured that he received a rigorous education in:

- Arabic grammar and Qur’anic recitation,

- Islamic jurisprudence,

- Persian theological texts,

- Sufism,

- and the classics of Confucianism, Daoism, and Neo-Confucian metaphysics.

From a young age, Liu Zhi was recognized for his extraordinary intellect, calm spiritual temperament, and ability to grasp complex ideas across different traditions.

He grew up speaking both the language of revelation and the language of Chinese philosophy — a rare and powerful combination.

📚 A Visionary Mission – Express Islam in the Chinese Philosophical Universe

While Ming-era scholars like Ma Fu and Wang Daiyu had begun translating Islamic truths into Confucian terms, Liu Zhi aimed higher.

He wanted not only to explain Islam to the Chinese world, but to show that Islam and Confucianism expressed the same universal realities, each with its own cultural path.

His mission was clear:

To demonstrate the unity of wisdom between the Islamic heart and the Chinese mind.

He believed truth was one, but its expressions many —

a concept deeply rooted in both Sufi metaphysics and Chinese thought.

📘 His Three Masterworks – The Crown Jewels of the Han Kitab

Liu Zhi’s writings form the core of the Han Kitab tradition, a body of Chinese Islamic literature unmatched anywhere else in the Muslim world.

1. Tianfang Xingli (天方性理) – “Nature and Principle in Islam”

This is Liu Zhi’s masterpiece — a metaphysical exploration of Islamic theology expressed in the language of Neo-Confucianism.

He describes:

- The nature of God (Allah) as the True One,

- The structure of creation,

- The hierarchy of existence,

- The soul’s journey toward perfection,

- And the unity of all spiritual principles.

He mapped Islamic metaphysics onto the Chinese categories of:

- Li (理) – Principle

- Qi (氣) – Material force

- Xin (心) – Heart-mind

- Tai Ji (太極) – Supreme Ultimate

This text is considered a philosophical masterpiece — proof that Islam could integrate with Chinese intellectual traditions without dilution.

2. Tianfang Dianli (天方典禮) – “Ritual and Law in Islam”

Here Liu Zhi explains:

- prayer,

- fasting,

- charity,

- moral discipline,

- social ethics,

- and legal principles

entirely in classical Chinese prose.

He showed that Islamic law (Sharia) was not foreign but a moral system parallel to Confucian ritual ethics (Li 禮).

This was groundbreaking — for the first time, Confucian scholars could understand Islamic practice in familiar conceptual terms.

3. Tianfang Zhisheng Shilu (天方至圣实录) – “The True Record of the Utmost Sage of Islam”

This is a biography of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ presented as a sage (圣人) — a title reserved in China for Confucius and Mencius.

Liu Zhi wrote:

“The Prophet is the Utmost Sage (至圣) whose teaching completes the Heavenly Way.”

He emphasized:

- the Prophet’s moral perfection,

- his compassion and justice,

- his role as a model for humanity,

- and the universality of his message.

By describing Muhammad ﷺ through Chinese sage terminology, Liu Zhi elevated his status in the eyes of the Chinese literati.

🌀 Philosophical Contributions – A Unified Theory of Truth

Liu Zhi’s works present a refined system of thought that merges Islamic metaphysics with Chinese philosophy.

1. The Unity of Existence (Wahdat al-Wujud) in Chinese Terms

Influenced by Sufi thinkers like Ibn Arabi and Jami, Liu Zhi translated the concept of Divine Unity into Neo-Confucian language.

He wrote:

“All beings are manifestations of the One Principle.”

This is the Chinese equivalent of la ilaha illa Allah understood metaphysically.

2. The Human Being as the Mirror of Heaven

He explained that the heart (xin) must be purified to reflect the Divine Light — a concept at home in both Sufism and Confucian self-cultivation.

3. Prophetic Wisdom as Universal Truth

Confucius and Muhammad were not opposites —

they were sages of different lands who taught the same eternal principles.

4. Harmony Between Revelation and Reason

Liu Zhi insisted that:

- reason confirms revelation,

- revelation completes reason.

This was a bold and elegant solution to philosophical disputes of his time.

🕌 Influence on Chinese Muslim Identity

Liu Zhi’s writings transformed Chinese Islam from a minority faith into a coherent philosophical system compatible with Chinese civilization.

He gave Hui Muslims:

- intellectual dignity,

- cultural depth,

- a sense of belonging,

- and theological confidence.

Mosque schools (jingtang) used his books for centuries.

Imams memorized his passages.

His metaphysical system became the standard for Muslim scholarship in China.

📜 Influence Beyond the Muslim World

Surprisingly, Liu Zhi’s works were also read by:

- Confucian scholars,

- Buddhist monks,

- Daoist masters,

- and even Qing officials.

His style was so elegant that many believed he belonged to the educated elite of their own tradition.

He demonstrated that Islam could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with China’s great philosophies.

🌠 Legacy – The Sage of the Crescent and the Dragon

Today, Liu Zhi is recognized worldwide as:

- the greatest Islamic philosopher China ever produced,

- a major global figure in comparative religion,

- a pioneer of cross-cultural theology,

- and a brilliant interpreter of Sufism.

His works continue to be studied in:

- China,

- Central Asia,

- Malaysia,

- Turkey,

- and Western academic institutions.

He remains the intellectual crown of the Han Kitab, the shining example of how two civilizations can meet not in conflict, but in wisdom.

📘 Liu Zhi in One Line

“He united the heart of Islam with the mind of China, and showed the world that wisdom has no borders.”

🧭 7. Ma Zhu (馬注) – The Voice of Orthodoxy and Reform

Dynasty: Qing (17th century CE)

Origin: Yunnan

If Wang Daiyu was the pioneer and Liu Zhi was the philosopher-sage, then Ma Zhu was the passionate reformer — the scholar who believed Islam in China could only survive if it remained strong, pure, disciplined, and morally grounded.

Living in the late 17th to early 18th century Qing Dynasty, Ma Zhu witnessed a Muslim community struggling with identity:

- Some Muslims were losing touch with Arabic learning,

- Mosque education was declining,

- Foreign Islamic connections had weakened,

- And Confucian pressure pushed Muslims to assimilate.

Ma Zhu rose as a voice of revival, determined to protect the faith from being diluted or forgotten.

He became the scholar who insisted that Islam must remain faithful to its roots while still flourishing within Chinese civilization.

🌙 Early Life – A Scholar of Yunnan’s Hui Heartland

Ma Zhu was born around 1640 CE in Yunnan, home to one of China’s oldest and strongest Hui Muslim populations.

Yunnan was a cultural crossroads where Islam had blended with local traditions for centuries.

From childhood, Ma Zhu was immersed in:

- Qur’anic learning,

- Arabic grammar,

- Islamic law (fiqh),

- Sufi teachings,

- and the local jingtang (mosque school) system.

Yet he also mastered:

- Confucian classics,

- the Four Books and Five Classics,

- Chinese poetry and prose,

- state philosophy and ethics.

This dual education shaped Ma Zhu into a Hui Confucian scholar (回儒) — similar to Wang Daiyu and Liu Zhi, but with a sharper, more reformist edge.

⚖️ The Scholar Who Refused Assimilation

Many Chinese Muslims of his era blended comfortably into Confucian culture — sometimes at the cost of losing Islamic knowledge.

But Ma Zhu saw a danger in this softness.

He believed:

“A faith forgotten in practice becomes a name without meaning.”

He admired Confucian ethics deeply, but feared that Muslims were beginning to identify culturally as Chinese first and religiously as Muslims second, forgetting the divine foundations of their spiritual life.

Thus, Ma Zhu dedicated himself to reviving Islamic orthodoxy, restoring discipline and clarity to the community.

📘 Major Work – Qingzhen Zhinan (清真指南) “The Compass of Islam”

Ma Zhu’s masterpiece, Qingzhen Zhinan, became the spiritual manual of Chinese Muslims.

This work is:

- a theological treatise,

- a practical guide,

- a philosophical commentary,

- and a call to reform.

The text covers:

- the Oneness of God (Tawhid),

- the nature of the soul,

- moral discipline,

- Islamic law (Sharia),

- Prophet Muhammad’s ﷺ role as the perfect guide,

- the importance of ritual practice,

- the dangers of ignorance and laxity.

Ma Zhu wrote with passion, clarity, and urgency.

He warned:

“A Muslim who understands Confucian virtue but forgets Islamic law is like a boat with a moral compass but no divine anchor.”

This sentence became central to Chinese Muslim identity debates for centuries.

🕌 Reviving Islamic Orthodoxy in China

Ma Zhu pushed for reforms across the Hui Muslim world. His goals:

1. Restore Arabic and Islamic learning

He strengthened jingtang education, demanding:

- Arabic accuracy,

- Qur’anic memorization,

- proper ritual performance.

2. Correct misunderstandings of Islamic belief

Some Chinese Muslims had developed folk practices influenced by local custom.

Ma Zhu argued fiercely for:

- theological purity,

- correct monotheism,

- avoidance of superstitions,

- strict moral behavior.

3. Reinforce Muslim community identity

He believed Muslims must maintain:

- proper marriage customs,

- dietary laws,

- mosque-centered social life,

- community leadership.

4. Present Islam as compatible with, yet distinct from, Confucianism

Ma Zhu agreed with Wang Daiyu and Liu Zhi that Islam and Confucian ethics complemented each other.

But he stressed:

“Confucianism teaches virtue.

Islam teaches both virtue and divine law.”

This distinction was crucial.

He wanted Muslims to appreciate Confucian culture without losing their Islamic essence.

📜 A Bold Thinker Who Challenged Both Sides

Ma Zhu’s writings challenged:

Confucian elites

He argued that Confucian virtue was insufficient without divine revelation.

This was daring, as Confucian scholars considered their system complete.

Complacent Muslims

He criticized Muslims who:

- abandoned Arabic study,

- imitated local customs blindly,

- or neglected ritual worship.

He believed Muslims should be:

- educated,

- disciplined,

- morally upright,

- religiously committed.

This reformist zeal made him a respected but controversial figure.

🌠 A Bridge Between Traditions, but With Strength

Unlike Liu Zhi’s harmonizing soft style, Ma Zhu’s approach was firm yet balanced.

He recognized:

- Confucian ethics as valuable for worldly conduct.

But insisted:

- Islamic revelation was necessary for spiritual salvation.

He articulated a formula:

**Confucianism = Harmonious Society

Islam = Harmonious Soul + Divine Guidance**

This became a guiding principle for many mosque schools.

🌏 Legacy – The Defender of Islamic Identity

Ma Zhu’s influence is enormous in Chinese Muslim history:

He:

- Reinforced Islamic orthodoxy,

- Revived mosque education,

- Preserved Arabic literacy,

- Strengthened Hui Muslim identity,

- Created doctrinal works still used today,

- Balanced faith and culture without surrendering either.

He is remembered as the scholar who ensured that Chinese Islam remained Islam, and not merely a cultural aesthetic.

Without Ma Zhu:

Much of Chinese Muslim tradition might have drifted into cultural assimilation.

🧭 Ma Zhu in One Line

“He was the compass that kept Chinese Islam aligned with its true direction: faithful to God, rooted in virtue, and unwavering in identity.”

⚙️ 8. Ma Jun – The Engineer and Inventor of Ancient China

Dynasty: Three Kingdoms (3rd century CE)

Origin: Possibly early Hui or Persian-descended family in Luoyang

In the turbulent days of the Three Kingdoms period (220–280 CE), when warlords clashed and empires shifted like sand, a quiet genius emerged whose inventions would shape Chinese engineering for centuries.

His name was Ma Jun, an engineer so gifted that ancient chroniclers called him:

“The greatest mechanic under Heaven.”

He was a visionary whose machines were centuries ahead of their time — a man whose mind blended mathematics, mechanics, and imagination into wonders that astonished emperors and generals alike.

Though he lived long before China’s Islamic civilization fully blossomed, Ma Jun is remembered by some historians as part of a lineage of artisans influenced by early Western and Central Asian mechanical traditions — traditions later embraced and expanded by Muslim engineers like al-Jazari.

In many ways, Ma Jun represents the proto-chapter of Muslim mechanical genius in the East.

🌙 Origins – The Mystery of His Heritage

Ma Jun’s early life is shrouded in mystery.

Historical sources list him as a native of Fufeng, near present-day Xi’an (the ancient gateway to the Silk Road).

His name and engineering style suggest:

- he may have descended from foreign craftsmen who migrated along the Silk Road,

- possibly Persian, Sogdian, or Arab engineers who settled in China centuries before Islam’s formal arrival,

- communities that were already bringing mechanical knowledge from the West into Chinese courts.

Regardless of ancestry, Ma Jun grew up surrounded by tools, gears, and ancient mechanical arts.

From childhood, he had a fascination with:

- wheels and axles,

- water power,

- automata (moving figures),

- and the physics of movement.

He would later apply this talent to create some of the most advanced machines in pre-Islamic China.

⚙️ The Genius Who Stunned the Kingdom of Wei

Ma Jun first entered history when he joined the court of Cao Wei, one of the three great kingdoms of the era.

When the emperor asked for a new design of a weaving loom — something more efficient than any before — Ma Jun delivered a masterpiece.

The Revolving Embroidery Machine (轉繡機)

This device allowed workers to embroider complex multi-colored patterns with incredible precision.

It was:

- faster,

- smoother,

- and mechanically superior

to all previous looms.

The emperor was astonished.

From that moment on, Ma Jun became the royal engineer — a position of high respect and political influence.

⚙️ The South-Pointing Chariot – China’s First Mechanical Compass Vehicle

Ma Jun’s most famous invention was the South-Pointing Chariot (指南車) — one of the greatest mechanical achievements of ancient China.

This machine had:

- no magnetic compass,

- no supernatural assistance,

- only pure mechanical engineering.

How It Worked

Using a differential gear system — the same principle used in modern automobiles — the chariot’s pointer always faced south, no matter how the vehicle turned.

This was centuries before gears of this complexity appeared in Europe.

Historians consider it:

- one of the earliest known applications of differential gears in the world,

- a masterpiece of mechanical reasoning,

- a precursor to later navigational tools.

The design influenced:

- later navigation systems,

- Ming dynasty shipbuilding,

- and even the conceptual development of the compass in Chinese-Muslim maritime science.

⚙️ Other Mechanical Wonders

Ma Jun engineered several extraordinary devices:

1. The Puppet Theater (木偶台)

A massive mechanical stage that featured moving figurines, rotating platforms, and automated scenery.

When activated, dozens of figures performed synchronized motions — a forerunner of mechanical automata found centuries later in Islamic and European traditions.

2. Water-Powered Machinery

He improved irrigation and agricultural devices, applying hydraulic principles that predated later Islamic and Renaissance innovations.

3. Military Machines

Ma Jun designed siege engines, defensive structures, and battlefield tools that strengthened the Wei kingdom’s military capabilities.

🧠 Engineering Philosophy – Nature, Calculation, and Harmony

Ma Jun believed machines should imitate natural forces.

His engineering followed three principles:

1. Balance of Opposites (陰陽之和)

Mechanisms must harmonize opposing forces — push and pull, rotation and rest.

2. Mathematical Precision (數術)

Every gear, axle, and wheel must be measured with exact proportion.

3. Moral Purpose

Machinery should serve society — weaving for families, defense for the kingdom, guidance for travelers.

His philosophy later resonated strongly with Muslim engineers like al-Jazari, whose works also united:

- technology,

- mathematics,

- and moral intention.

🌠 Legacy – A Pioneer of Mechanical Engineering

Ma Jun’s influence is vast:

⭐ 1. He pioneered differential gearing

Long before Europe, China, or Islamic engineers fully systematized it.

⭐ 2. He inspired future inventors

Chinese, Persian, and Arab engineers adopted similar mechanical principles centuries later.

⭐ 3. He set the stage for maritime navigation

The south-pointing chariot concept influenced navigational thought that would later be expanded by:

- Muslim astronomers in China,

- the Yuan-era Islamic Astronomical Bureau,

- the navigators of Zheng He’s fleets.

⭐ 4. He represents an early fusion of East and West mechanical thought

Even if not Muslim himself, Ma Jun embodies the Silk Road tradition of cross-cultural innovation — a tradition that Muslims carried to new heights in later centuries.

🧭 Ma Jun in One Line

“The man who built machines so advanced that even emperors bowed to his genius — a pioneer whose gears turned the wheels of Chinese engineering for a thousand years.”

🌏 9. Ma Dexin (馬德新) – The Modernizer of Chinese Islam

Dynasty: Late Qing (19th century CE)

Origin: Yunnan

In the final centuries of imperial China, when Qing rule tightened and the world was rapidly changing, one Muslim scholar stood out as a visionary who sought to reconnect Chinese Islam with the broader Muslim world.

This man was Ma Dexin, the most widely traveled, internationally educated, and globally aware Muslim thinker China had ever produced.

A scholar of immense courage, intellect, and spiritual depth, Ma Dexin became:

- the first major Chinese Muslim to study in Mecca, Cairo, and Damascus,

- a leading translator of Islamic classical texts,

- a reformer who aimed to strengthen Chinese Muslim identity,

- and a mediator during one of the bloodiest rebellions in Chinese history.

His life reads like an epic — from the mountains of Yunnan to the libraries of Al-Azhar University, from the mosques of Mecca to war-torn cities of southwest China.

🌙 Early Life – A Scholar Born in Yunnan’s Muslim Heartland

Ma Dexin was born in 1794 in Kunming, Yunnan Province — a region with one of the richest Islamic traditions in China.

The Hui Muslim communities of Yunnan were known for:

- strong religious learning,

- deep Sufi roots,

- martial discipline,

- vibrant mosque education,

- and established trade networks with Southeast and South Asia.

From an early age, Ma Dexin showed exceptional intelligence.

He memorized the Qur’an as a child, mastered Arabic in local jingtang schools, and studied classical Chinese literature and Confucian philosophy.

But while most of his contemporaries remained isolated from the global Muslim world, Ma Dexin dreamed of reconnecting Chinese Islam with the centers of traditional scholarship.

🕋 Journey to Mecca – A Transformation Begins

At age 34, Ma Dexin embarked on a journey few Chinese Muslims had undertaken in centuries — the Hajj pilgrimage.

His route took him through:

- Southeast Asia,

- India,

- the Arabian Sea,

- the Red Sea,

- and finally Mecca and Medina.

This pilgrimage was life-changing.

In the holy cities of Islam, Ma Dexin studied:

- Arabic grammar and philology,

- Hadith sciences,

- Tafsir (Qur’anic exegesis),

- Kalam (Islamic theology),

- Sufism,

- Islamic law (Shafi‘i and Hanafi traditions).

He spent eight years in the Middle East, traveling between:

- Mecca,

- Cairo,

- Damascus,

- Istanbul,

- and Jerusalem.

At Al-Azhar University, he studied under some of the greatest scholars of the time.

He returned to China not just as a scholar, but as a global Muslim intellectual.

📚 A Scholar of Enormous Output – Translator, Commentator, Innovator

Ma Dexin produced one of the largest bodies of Islamic writing in Chinese Muslim history.

His works include:

- translations of classical Arabic texts,

- commentaries on Qur’anic verses,

- explanations of hadith,

- Sufi treatises,

- legal discussions,

- and guidance for Chinese Muslim community reform.

📘 His Most Important Texts Include:

1. Zhengjiao Zhinan (正教指南) – “Guide to the True Teaching”

A monumental work explaining Islamic theology, cosmology, and ethics to Chinese Muslims.

2. Chinese Commentary on the Qur’an (古兰经注)

Ma Dexin became one of the first scholars in China to produce a full, accurate interpretation of the Qur’an based directly on Arabic sources.

This work revitalized Chinese Quranic study.

3. Translations of Arabic Classics

He translated:

- al-Ghazali’s works,

- Sufi treatises,

- Islamic jurisprudence manuals,

- and parts of Ibn Arabi’s metaphysics.

4. Tianfang Dianli Bian (天方典礼辨)

A text explaining Islamic rituals and law while correcting misunderstandings within local Chinese Muslim practice.

Through these writings, Ma Dexin reunited Chinese Muslims with centuries of Islamic intellectual tradition.

⚖️ Faithful Reformer – The Defender of Orthodoxy

Ma Dexin believed Chinese Muslims had drifted too far from Islamic orthodoxy — not intentionally, but through isolation.

He pushed for:

- proper Arabic study,

- correct ritual practice,

- revival of classical Islamic law,

- purification of folk customs,

- moral discipline,

- mosque-centered education.

But unlike the earlier reformer Ma Zhu, Ma Dexin had directly studied in the Middle East — giving him unprecedented authority.

His writings became the blueprint for:

- modern Chinese Muslim scholarship,

- standardized mosque education,

- and renewed connection to global Islam.

🕌 Spiritual Depth – A Scholar of Sufism

Ma Dexin was deeply influenced by:

- Naqshbandi Sufi traditions,

- Middle Eastern spiritual teachers,

- contemplative practices.

He wrote extensively on:

- purification of the heart,

- inner unity with divine will,

- the metaphysics of existence,

- moral self-discipline.

His Sufi works often echoed themes from Ibn Arabi, Jami, and al-Ghazali — but expressed in Chinese literary style.

⚔️ Mediator During the Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873)

When the Panthay Rebellion erupted — a Muslim uprising against Qing oppression — Ma Dexin tried desperately to mediate peace.

He believed:

- Muslims should defend themselves,

- but also avoid unnecessary bloodshed,

- and maintain Qur’anic ethics even in war.

He wrote letters urging:

- negotiation,

- compromise,

- justice,

- restraint.

Both sides respected him, but neither fully listened.

The rebellion spiraled into massive violence.

Hundreds of thousands died.

Despite accusations from both sides, Ma Dexin remained focused on saving lives and preserving the Muslim community.

He died in 1874, shortly after the rebellion’s collapse.

🌠 Legacy – The Last Great Scholar of Imperial Chinese Islam

Ma Dexin’s influence is profound:

⭐ 1. First Chinese Muslim to deeply study abroad in centuries

Reconnecting China with global Islamic scholarship.

⭐ 2. Major translator of Arabic classics

Making Islamic knowledge accessible to Chinese Muslims.

⭐ 3. Reformer of mosque education

Standardizing Qur’anic and Arabic instruction.

⭐ 4. Sufi guide and theologian

Bringing spiritual and intellectual depth to Chinese Islam.

⭐ 5. Diplomat and peace-seeker

Trying to prevent the destruction of his community during rebellion.

He is remembered as:

“The scholar who brought China back into the heart of the Muslim world.”

Without Ma Dexin, Chinese Islam might have remained isolated and intellectually stagnant.

🧭 Ma Dexin in One Line

“A traveler between worlds, he carried the wisdom of Mecca and Cairo back to China, renewing a faith, rebuilding a community, and preserving a civilization.”

🕊️ 10. Sayyid Ajall Shams al-Din Omar (賽典赤·贍思丁)

Dynasty: Yuan (13th century CE)

Origin: Bukhara (Central Asia)

Among the great architects of Chinese civilization, few figures are as extraordinary — or as overlooked — as Sayyid Ajall Shams al-Din Omar.

A Muslim noble from Central Asia, he became one of the most powerful governors of the Yuan Dynasty, and the man who laid the cultural and administrative foundations of Yunnan Province, transforming it from a frontier region into a fully integrated part of China.

He was a builder of cities, a promoter of education, a champion of interfaith coexistence, and a statesman who blended Islamic ethics with Confucian governance in a way unmatched by any figure of his era.

Sayyid Ajall stands as one of the few individuals in world history who shaped the destiny of a major region of China — and yet remains almost unknown outside scholarly circles.

🌙 Origins – A Noble Lineage from Bukhara

Sayyid Ajall was born around 1211 CE in Bukhara (Central Asia), a city famous for:

- Islamic scholarship,

- Sufi tradition,

- Persian culture,

- mathematics,

- philosophy, and

- trade networks spanning thousands of miles.

He belonged to a family claiming descent from the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, making him a Sayyid — a lineage that commanded deep respect across the Muslim world.

When the Mongols conquered Central Asia, Sayyid Ajall entered imperial service, and his brilliance quickly caught the attention of Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan and founder of the Yuan Dynasty in China.

🏛️ Rise to Power – The Muslim Trusted by Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan was a visionary ruler who valued talent above ethnicity.

Sayyid Ajall’s combination of:

- Islamic ethics,

- Persian administrative expertise,

- deep education, and

- diplomatic skill

made him invaluable to the Mongol court.

He rose through the ranks to become:

- Minister of Finance,

- Senior Administrator,

- Imperial Advisor, and eventually

- Governor of Yunnan, one of the most strategic regions in the empire.

No Muslim before him had held such high office in China.

🌏 Transforming Yunnan – From Frontier Wilderness to Civilizational Center

Before Sayyid Ajall, Yunnan was a rugged frontier of tribal kingdoms and diverse ethnic groups.

It lacked:

- centralized administration,

- large-scale agriculture,

- Confucian education,

- and integration with the rest of China.

Sayyid Ajall changed that completely.

⭐ 1. He established Confucian schools and examination systems

He built the first Confucian temple in Yunnan and introduced the civil service curriculum.

⭐ 2. He built infrastructure and reorganized cities

Sayyid Ajall laid out the city of Kunming using Persian-style urban planning combined with Chinese architectural order.

He built:

- roads,

- bridges,

- markets,

- irrigation systems.

⭐ 3. He promoted agriculture and economic development

He brought:

- new farming techniques,

- hydraulic engineering,

- and administrative structures

that transformed Yunnan’s economy.

⭐ 4. He encouraged peaceful integration of tribes

Rather than forcing assimilation, he used diplomacy, education, and incentives to unite ethnic groups under Yuan governance.

⭐ 5. He introduced Islamic moral values into public administration

He emphasized:

- justice,

- fairness,

- honesty,

- community welfare.

Contemporary sources note that his rule was remarkably humane for the era.

🕌 Builder of Mosques and Protector of Pluralism

Sayyid Ajall believed that a harmonious society required respect for all religions.

In Yunnan, he built:

🌙 Mosques for Muslims

Including the famous Nancheng Mosque, one of the oldest in China.

🏛️ Confucian temples for scholars

To teach ethics and state principles.

🕉️ Buddhist and Daoist temples for local communities

To maintain cultural continuity.

This multi-faith governance model was centuries ahead of its time — a peaceful coexistence that modern societies still struggle to achieve.

📜 The Ethical Statesman

Sayyid Ajall’s leadership style was deeply influenced by Islamic morality and Sufi teachings, combined with Confucian virtues.

He taught that:

- A ruler must be humble

- Justice is a divine command

- Knowledge is the foundation of society

- Ethnic diversity is a strength

- Governance must benefit the people

- Violence should be minimized

Local Yunnan traditions still remember him as:

“The benevolent governor who brought peace, learning, and prosperity.”

His governance model became the blueprint for Chinese administration in frontier regions for centuries.

🌠 Legacy – Father of Yunnan’s Hui Muslim Community

Sayyid Ajall is considered the forefather of many Hui Muslim families in Yunnan, including — most famously — the lineage that would produce:

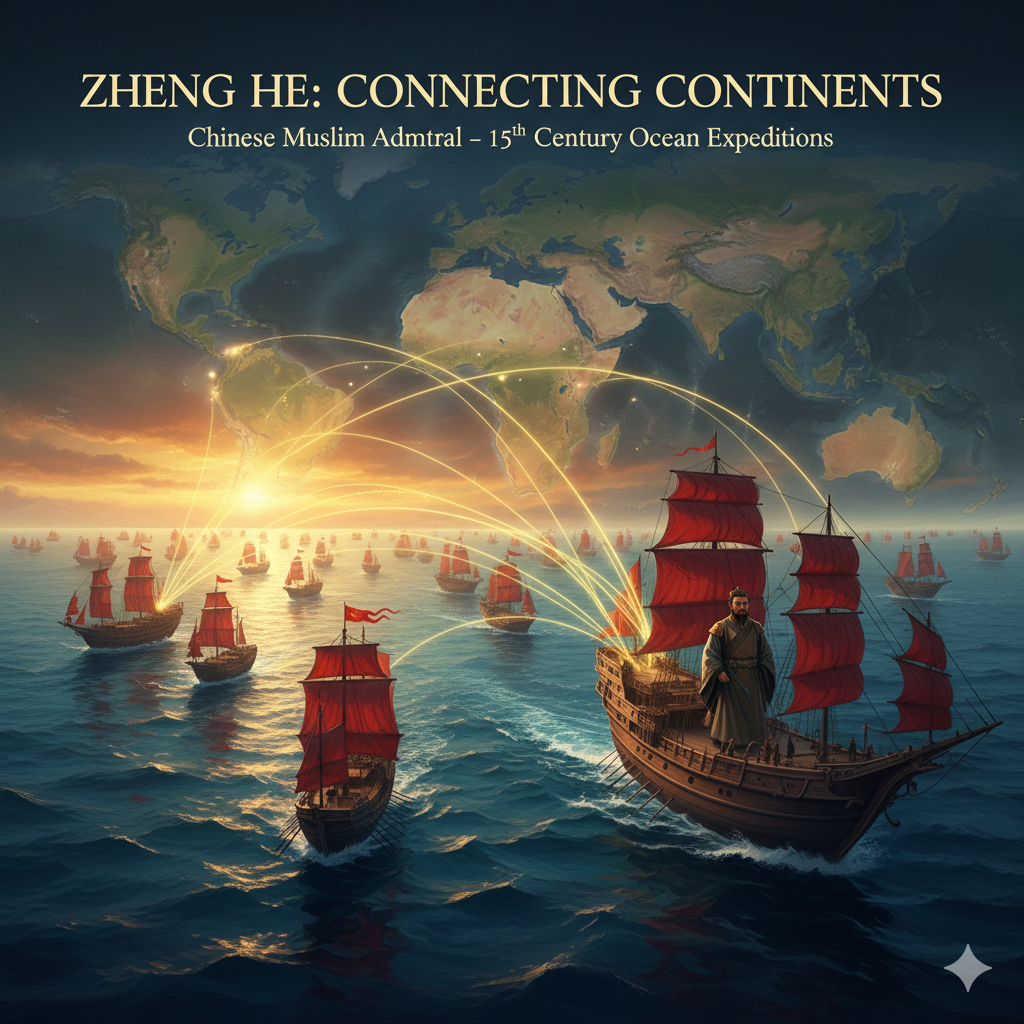

⭐ Zheng He (鄭和)

The greatest admiral in Chinese history.

Zheng He’s family traced its roots directly to Sayyid Ajall’s descendants.

Thus, Sayyid Ajall’s legacy extended not only through government but across centuries of Muslim leadership and scholarship in China.

He is remembered as:

- the civilizer of Yunnan,

- the bridge between Islam and China,

- a master administrator,

- and one of the most influential Muslim figures in East Asian history.

🧭 Why Sayyid Ajall Matters Today

His story challenges modern assumptions:

✔ Islam and Chinese civilization were not enemies

They coexisted and flourished together under visionary leadership.

✔ Muslims played high-ranking roles in Chinese governance

Serving as ministers, governors, and advisors.

✔ Multi-religious harmony is possible

Sayyid Ajall built institutions of all major religions side by side.

✔ Identity does not need to be sacrificed for integration

He stayed Muslim, stayed devout — yet served China loyally and shaped its destiny.

📘 Sayyid Ajall in One Line

“A Muslim statesman who united empires, shaped a province, and proved that wisdom and justice know no borders.”

🌙 Conclusion – The Crescent That Shaped the Middle Kingdom

Across the vast expanse of Chinese history, stretching from the ancient dynasties to the dawn of the modern world, Muslims played roles far greater than the pages of mainstream history reveal.

They were astronomers and philosophers, generals and governors, reformers and poets, engineers and navigators — each contributing silently yet powerfully to the rise, stability, and intellectual richness of China.

Taken together, the ten personalities we explored form a hidden constellation — a network of bright stars whose light illuminates the forgotten truth that Islam was not a foreign footnote in Chinese civilization, but a living, shaping force.

⭐ A Bridge Between Civilizations

From Ma Yize, who introduced the precision of Islamic astronomy to the Song court,

to Chang Yuchun and Lan Yu, whose courage helped forge and defend the Ming Dynasty,

to Ma Jun, whose engineering brilliance predated the Golden Age of Islamic mechanics,

Muslim influence was as scientific as it was political.

And from Ma Fu, Wang Daiyu, Liu Zhi, and Ma Zhu, who blended Islamic theology with Confucian ethics,

to Ma Dexin, who reconnected China to the heart of the Muslim world,

and Sayyid Ajall, the Muslim statesman who shaped Yunnan and laid the groundwork for Zheng He’s lineage —

their lives show that Islam in China was not merely tolerated; it thrived, adapted, enriched, and evolved.

⭐ A Legacy of Knowledge, Courage, and Wisdom

These figures demonstrated that cultural exchange is not a threat but a source of strength.

Islamic astronomy strengthened Chinese cosmology.

Islamic ethics reinforced Confucian morality.

Islamic governance principles influenced Chinese administration.

Muslim navigators and generals protected Chinese borders and connected China to oceans and continents beyond.

Far from being outsiders, Muslims were builders of dynasties, architects of provinces, and authors of philosophical systems that still echo through academic circles today.

⭐ The Forgotten Chapter We Must Remember

Why were these figures forgotten?

Because later eras emphasized ethnic uniformity.

Because political suspicion erased contributions of minorities.

Because the story of China was simplified into a single narrative — one that left little room for the diversity that once made it vibrant.

But the truth remains unshaken:

Muslims shaped Chinese civilization — and China shaped Islam.

This exchange created a unique heritage that belongs to both worlds.

⭐ A Message for Today

In an era where misunderstandings often divide cultures, the lives of these ten figures offer a powerful lesson:

**Civilizations do not clash — they converse.

Faiths do not collide — they coexist.

Cultures do not weaken each other — they enrich one another.**

The forgotten Muslims of Chinese history stand as proof that when wisdom flows across borders, humanity reaches its highest potential.

🌠 Final Line

These ten lives — scientists, warriors, sages, and governors — remind us that the story of China is not complete without the Crescent, and the story of Islam is not complete without the Dragon.

These forgotten Muslim figures were more than names — they were bridges: between East and West, faith and reason, Heaven and Earth.