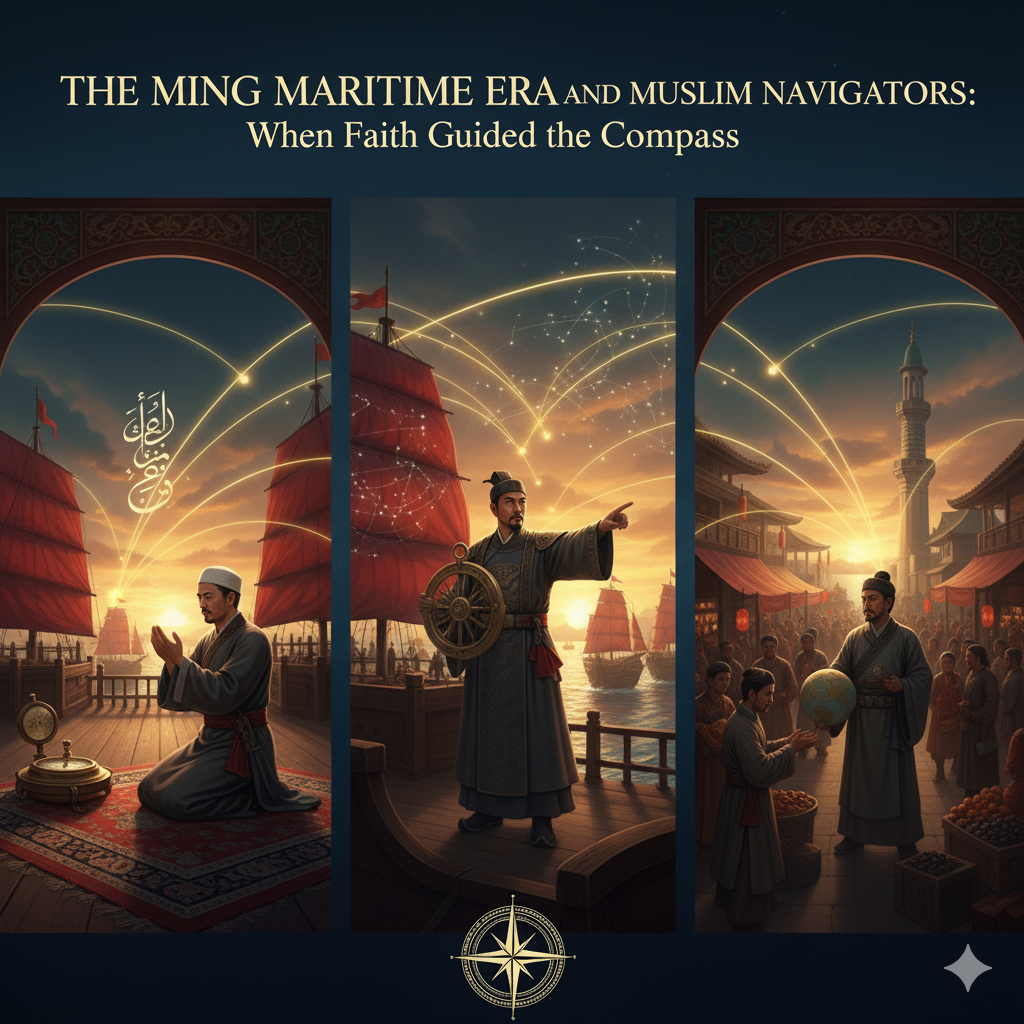

In the early 15th century, while Europe’s explorers still traced coastlines with trembling hands, one man from China commanded an oceanic empire that stretched from the Pacific to the coasts of Africa.

That man was Zheng He (1371–1433) — the Great Eunuch Admiral of the Ming Dynasty, a Muslim mariner, diplomat, and visionary who led the largest naval expeditions the world had ever seen.

Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He led seven grand voyages, commanding fleets of over 300 ships and 27,000 crewmen, traversing the Indian Ocean, visiting Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and East Africa. His ships — massive “Treasure Ships” that dwarfed the vessels of later European explorers — carried silk, porcelain, and knowledge, but also peace offerings and letters of friendship.

While Columbus sailed with ambition, Zheng He sailed with diplomacy.

He wasn’t seeking conquest, gold, or slaves — he sought connection.

He came not as a colonizer but as a messenger of civilization, uniting continents under the banner of trade, culture, and mutual respect — long before the word globalization was even imagined.

Early Life – From Ma He to Zheng He

Zheng He was born in 1371 CE in Kunyang, Yunnan Province, during the final years of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty. His birth name was Ma He, and he came from a devout Muslim family of Hui ethnicity. His father and grandfather were known to have made the pilgrimage to Mecca — a legacy that infused young Ma He with spiritual discipline and a global sense of belonging.

In 1382, when the Ming dynasty reconquered Yunnan, Ma He was captured and taken to the imperial court as a child servant. There, his intellect, loyalty, and strategic mind caught the attention of Prince Zhu Di, who would later become Emperor Yongle, one of China’s greatest rulers.

Under Yongle’s patronage, Ma He was trained in diplomacy, strategy, and navigation. Upon proving his brilliance and loyalty, he was granted the imperial surname Zheng, becoming Zheng He — a title that would soon echo across oceans.

Despite being a eunuch — a condition that often limited power in court politics — Zheng He defied every limitation, rising to become Grand Admiral of the Ming Fleet, second only to the emperor himself in command.

The Great Voyages – China’s Age of Maritime Glory

🌊 The First Voyage (1405–1407)

The year was 1405 CE, and the world had never seen anything like it.

From the mighty docks of Longjiang Shipyard near Nanjing, a fleet larger than any before — or since — prepared to sail under the command of Admiral Zheng He, the trusted envoy of the Ming Emperor Yongle.

Over 300 ships lined the Yangtze River, their red banners snapping in the wind, their hulls glistening with lacquer and gold. At the fleet’s heart were the colossal Treasure Ships (Baochuan) — wooden giants stretching nearly 120 meters (400 feet) long, their nine masts towering like forests above the river.

Each ship could carry hundreds of men, precious cargo, and enough supplies to sustain transoceanic voyages lasting years.

The fleet embarked from Nanjing, the imperial capital, sailing down the Yangtze River to the South China Sea, stopping briefly at Liujiagang — where Zheng He performed rituals to honor Mazu, the goddess of the sea, and prayed for protection for his men.

Then, with the blessings of Heaven and the Emperor, the fleet turned south, cutting across the South China Sea.

Their mission was not conquest or colonization — it was diplomacy on a grand scale.

⚓ The Route and Encounters

From the coasts of Vietnam and Champa (modern-day central Vietnam), the fleet sailed onward to the Malay Peninsula, establishing new tributary relations and reaffirming China’s presence in Southeast Asia.

They then passed through the narrow and strategic Straits of Malacca, a vital trade corridor where Chinese, Indian, and Arab merchants converged.

Here, Zheng He intervened in local politics, supporting the Sultan of Malacca against rival claimants and thus laying the foundation for Malacca’s rise as a global trade hub.

In return, the Sultan pledged loyalty to the Ming Emperor — the first of many such alliances formed through diplomacy, not war.

From Malacca, the fleet crossed the open Indian Ocean, navigating by celestial stars, magnetic compasses, and advanced Chinese maritime charts — centuries ahead of their European counterparts.

Their journey led them to the bustling Indian ports of Cochin and Calicut (in present-day Kerala), both thriving centers of the spice trade. There, Zheng He met with the local rulers, including the Zamorin of Calicut, exchanging letters, gifts, and ambassadors on behalf of Emperor Yongle.

It was a meeting of equals — the Ming Empire offering friendship, not dominance. The emissaries of China presented the Zamorin with silk, porcelain, jade, and gold-threaded brocades — symbols of prosperity and peace. In return, Indian merchants offered spices, precious stones, and medicinal herbs, treasures that would fill the holds of Zheng He’s ships on their journey home.

🌏 Diplomacy Over Conquest

Unlike European explorers who would sail a century later, Zheng He’s voyage was not a search for new worlds — it was the reaffirmation of an interconnected one.

His ships carried letters of friendship, official seals, and imperial gifts — establishing the Ming Emperor’s goodwill while reinforcing China’s prestige as a benevolent superpower.

These exchanges formed the foundation of what historians now call the Ming Tribute System — a network of partnerships that promoted trade, peace, and cultural exchange across Asia and beyond.

The admiral’s first voyage established China not as an isolated empire, but as a cosmopolitan civilization, capable of reaching across oceans through diplomacy, technology, and faith.

His sailors included Muslims, Buddhists, and Confucians; his translators spoke Arabic, Tamil, and Persian; his maps charted new routes that would later guide traders for generations.

Zheng He’s fleet returned to China in 1407 with envoys from distant lands, exotic animals such as camels and peacocks, and countless artifacts — not as trophies of war, but as symbols of friendship.

🕊️ The Message Behind the Voyage

The first voyage was a declaration — not of empire, but of intent.

It announced to the known world that the Ming Dynasty sought not domination, but harmony; not to rule the seas by force, but to connect civilizations through respect and exchange.

Zheng He’s fleet was an empire on water — yet one guided by diplomacy, faith, and purpose.

Every sail carried the emblem of the dragon and the crescent, a reflection of his dual heritage:

the might of China and the serenity of Islam.

In that first journey, he not only mapped trade routes — he charted a moral geography of how power could coexist with peace.

And thus began the greatest era of exploration the East had ever known — an era when ships from the Middle Kingdom reached the edge of Africa, and the world discovered that the ocean, when crossed with goodwill, could unite rather than divide.

🌍 The Second to Sixth Voyages (1407–1424)

Across these voyages, Zheng He visited Java, Sumatra, Sri Lanka, Malacca, India, Hormuz, and the Arabian Peninsula, establishing China’s presence in ports that would later become key global trade routes. He exchanged envoys with Muslim rulers, strengthened alliances with Hindu kingdoms, and built bridges of culture and commerce.

He even reached the Swahili Coast of East Africa — Kenya, Somalia, and possibly Mozambique — long before any European ship sighted those shores. In return, African rulers sent back giraffes, zebras, and ostriches to the Ming court — wonders that the emperor viewed as signs of Heaven’s favor.

🕌 Faith and Identity

Though serving a Confucian court, Zheng He remained a devout Muslim.

During his voyages, he built mosques in China and abroad, particularly in Nanjing and Chittagong, and is believed to have performed the Hajj. His faith and diplomacy allowed him to interact seamlessly with Muslim traders from Arabia and East Africa, forming lasting cultural ties.

Diplomacy, Not Domination

What sets Zheng He apart from later explorers is his purpose.

He did not seek colonies, nor did he plunder. His fleet carried translators instead of missionaries, and gifts instead of guns.

Where Europeans sought to control, Zheng He sought to connect.

He established diplomatic relations with more than 30 kingdoms, fostering trade and mutual respect under the Ming tribute system — a network of trust rather than tyranny.

His approach was guided by a distinctly Islamic ethic of peaceful exchange and the Confucian principle of harmony. In him, East and West met not in conflict, but in collaboration.

Decline and Disappearance – The Last Voyage of the Dragon Fleet

By the early 1430s, the tides of history had begun to turn against Zheng He.

The Yongle Emperor, his great patron and the architect of China’s maritime age, had passed away in 1424. His death marked not just the end of an emperor, but the eclipse of an entire vision — a vision of a China that ruled the seas through prestige, curiosity, and grace.

🏯 The Waning of the Ming Maritime Dream

The new emperor, Hongxi, and his successor Xuande, were more cautious rulers. They saw the grand expeditions as costly luxuries that drained the imperial treasury and threatened the Confucian ideal of agrarian stability.

Court scholars, particularly conservative Neo-Confucians, argued that China’s greatness lay not in the ocean but in its moral and agricultural order. To them, Zheng He’s vast fleets — with their gold-leafed decks, foreign ambassadors, and exotic animals — represented extravagance and distraction, not strength.

Gradually, the once-mighty Treasure Fleet began to wither. Dockyards in Nanjing fell silent. Shipwrights who had once built the largest vessels on earth were reassigned to constructing river barges. Maritime records were sealed, and the blueprints of Zheng He’s ships — marvels of naval architecture — were destroyed or hidden, as if China wished to forget its time as a maritime empire.

Yet, Emperor Xuande, aware of Zheng He’s loyalty and the respect he commanded across the seas, authorized one final voyage — a farewell to an era that was ending.

🌊 The Seventh Voyage (1431–1433) – The Admiral’s Last Horizon

In 1431, an aging Zheng He once again stood on the decks of his flagship. His hair had grayed, his health had weakened, but his resolve remained the same. He commanded a smaller fleet, still magnificent by any standard — about 100 ships carrying diplomats, merchants, physicians, and interpreters.

This last expedition retraced familiar waters: from Nanjing to Quanzhou, through the South China Sea, past Sumatra, Sri Lanka, and Calicut, and onward to the Arabian Peninsula and the Swahili Coast of East Africa.

He revisited the kingdoms of Hormuz, Aden, and Malindi, reaffirming China’s friendship and exchanging gifts with rulers who remembered the Admiral’s earlier visits. The voyage carried fewer treasures but deeper meaning — it was a final salute to the oceans that had carried his dreams.

Along the African coast, Zheng He sent emissaries to local rulers, mapping ports and strengthening trade relations one last time. Chinese records mention his fleet returning with rare goods — spices, pearls, medicinal herbs, and exotic animals — but also envoys and scholars who accompanied him back to China.

By 1433, his ships once again reached Calicut, that symbol of his youth and glory, before beginning their long return across the Indian Ocean. But for Zheng He himself, it would be a journey without return.

⚓ Death of the Admiral

Accounts differ on how Zheng He’s life ended, and perhaps it is fitting that a man of the sea left behind only waves for evidence.

Some chronicles say that he fell ill during the return voyage, somewhere between Calicut and the Strait of Malacca, and died at sea — buried in the Indian Ocean he had spent his life crossing. Sailors said they lowered his body into the depths wrapped in silken shrouds, with his command flag folded at his chest and a compass placed by his heart.

Other sources claim he returned to Nanjing, where he died quietly that same year.

His tomb, built on the Niushou Hill overlooking the Yangtze River, remains empty — a symbolic resting place, for his body was never found.

Even his tombstone reflects the duality of his life: it bears Buddhist, Taoist, and Islamic inscriptions, a perfect mirror of the Admiral’s world — a world not divided by belief but bound by curiosity, tolerance, and faith in human connection.

🌅 The Vanishing of the Great Fleet

After Zheng He’s death, the Ming court dismantled what remained of his naval empire.

The shipyards were shuttered. The great logs of his voyages — including detailed nautical maps, weather records, and trade accounts — were sealed or destroyed by officials who feared that future generations might resurrect the costly dream of oceanic expansion.

In less than a decade, the empire that had once ruled the seas withdrew into itself. By the time Columbus was born (1451), China had already turned its back on the ocean.

Zheng He’s name faded into legend. For centuries, his story lived only in fragments — in temple inscriptions, sailors’ songs, and the memories of African and Arab coastal towns that still told of “the Great Chinese Admiral who came in peace.”

🌊 The Symbol and the Silence

His empty tomb stands today as both a monument and a metaphor — the silence of an empire that had once commanded the world’s horizons.

Zheng He embodied what China could have become: a nation defined by exploration, innovation, and dialogue rather than isolation.

And though his ships rotted and his charts were lost, his spirit endures wherever seas meet — in every port that welcomes strangers as friends, in every culture that trades knowledge as freely as goods.

He sailed at a time when humanity’s maps ended in mystery.

And when he disappeared into that mystery, he left behind not borders — but bridges of memory that still stretch across oceans today.

“He who sails farthest,” a Chinese proverb says, “sees the most stars.”

Zheng He saw them all — and then became one.

Legacy – The Forgotten Navigator of the World

When Zheng He’s final fleet vanished beyond the horizon, the waves closed behind him as though the ocean itself wished to guard his story. For centuries, his name faded into the quiet corners of Chinese chronicles, overshadowed by emperors and philosophers. Yet, what he left behind was not a tomb of stone, but a legacy that stretches across oceans — a testament to human curiosity, faith, and unity.

🌏 1. The Diplomat Who United Continents

Zheng He’s voyages were not campaigns of conquest — they were missions of connection.

In a world divided by geography and empire, he built bridges of diplomacy linking Asia, Africa, and the Middle East under the idea of mutual respect.

His fleets established relations with over 30 kingdoms across the Indian Ocean, from Java and Ceylon to Aden, Hormuz, and Malindi.

He brought tribute and gifts, but more importantly, he brought dialogue — letters of goodwill, interpreters, and scholars who represented the Ming Emperor’s intention to trade, not to conquer.

He introduced the world to the concept of soft power centuries before the term existed.

Where European explorers carried the sword, Zheng He carried silk, spices, and friendship.

His voyages became a living manifestation of an idea deeply rooted in both Confucian and Islamic ethics:

that harmony, justice, and exchange are stronger than domination.

⚓ 2. The Master of Maritime Innovation

Zheng He’s expeditions marked the apex of pre-modern naval technology.

His Treasure Ships, some over 400 feet long, used compartmentalized hulls, watertight bulkheads, and balanced rudder systems — innovations not replicated in Europe until the 19th century.

His fleets carried:

- Astronomers and navigators, who charted celestial maps with unparalleled precision.

- Engineers, who designed self-repairing hull systems.

- Medical officers, who used herbal remedies to prevent disease during long voyages.

The Ming fleet’s use of magnetic compasses, detailed maritime charts (航海图), and star-based navigation proved that Chinese seafarers were centuries ahead of their Western counterparts in understanding global geography.

In essence, Zheng He’s armada was not only a symbol of imperial might but a floating university, combining science, diplomacy, and faith on a scale no empire had attempted before.

🌍 3. The Cultural Ambassador of a Global Civilization

Everywhere Zheng He went, he left behind more than trade routes — he left cultural echoes that still survive in architecture, language, and tradition.

In Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia and Malaysia, communities of Chinese Muslims trace their heritage to Zheng He’s sailors and merchants. Shrines in Java, Palembang, and Malacca still honor him — sometimes as an admiral, sometimes as a saint, often as both.

In Sri Lanka, inscriptions at Galle record his presence; in Kenya, oral traditions remember the “Great Chinese” who came bearing gifts, not armies.

In Malacca, the famous Sam Po Kong Temple stands as a fusion of Chinese and Islamic architecture — a place where locals still light incense and recite prayers for the admiral who brought peace and trade.

Through these stories, Zheng He became a symbol larger than empire — a figure of unity whose voyages transcended politics, religion, and geography.

🕊️ 4. The Forgotten Legacy

After Zheng He’s death, China turned inward. The Ming court, influenced by isolationist officials, banned oceanic trade, destroyed shipyards, and outlawed large-scale voyages.

It was as if the empire, weary of its own greatness, feared what it had achieved.

Maps and records of Zheng He’s journeys were burned; sailors were reassigned to river patrols.

By the 16th century, when European explorers like Columbus, da Gama, and Magellan began to sail, China’s once-great fleet had become a ghost of memory.

And so, history was rewritten — the narrative of discovery shifted westward.

Europe claimed the “Age of Exploration,” while the man who had already mapped the Indian Ocean was nearly erased from collective memory.

It would take centuries before historians and archaeologists would rediscover the scope of his journeys, piecing together his story from Arab accounts, Ming records, and African oral traditions.

🕌 5. Zheng He’s Faith and Moral Compass

At the heart of Zheng He’s voyages was faith — a faith not of conquest, but of creation.

Born a Muslim in Yunnan and educated in Confucian China, he carried both the discipline of Islam and the ethics of Confucian harmony wherever he sailed.

He built mosques in Nanjing, Chittagong, and Semarang, ensuring that every new horizon included a place for prayer.

He embodied the Islamic principle of ta’aruf — to know one another through peaceful exchange — and the Confucian concept of tianxia — “all under heaven,” a world united under moral order.

In Zheng He, the ocean found its moral navigator — a leader whose strength was matched by humility.

🌠 6. Rediscovery and Modern Relevance

In the modern era, China has revived Zheng He’s image as a symbol of diplomacy, maritime strength, and multicultural harmony.

His story now represents China’s historical connection to Africa and the Muslim world, emphasizing peaceful exchange rather than imperial ambition.

Museums, films, and monuments in China, Malaysia, and Kenya celebrate his voyages.

The UNESCO Silk Road Project recognizes his contributions as key to global cultural exchange.

Even the Chinese Navy has named one of its training vessels Zheng He, carrying students across the same waters he once commanded.

But perhaps the most important revival is not political — it’s philosophical.

In a world fractured by power struggles, Zheng He’s legacy offers a blueprint for a different kind of leadership:

one that measures greatness not by conquest, but by connection.

🌊 7. The Eternal Admiral

Zheng He’s story begins in China but belongs to the world.

He was a Muslim who served a Confucian emperor, a Chinese who spoke with Africans and Arabs, a sailor who saw the Earth as one boundless horizon.

Six centuries later, his compass still points toward the future — reminding us that every voyage worth taking begins not with domination, but with understanding.

He was a man of two worlds — faith and reason, East and West, land and sea — and yet, he proved that all worlds can coexist in harmony.

And so, while his tomb remains empty, his legacy is full — alive in every act of diplomacy, every exchange of cultures, every ship that sails toward another shore not to conquer, but to learn.

“To sail is to seek, to seek is to know, and to know is to unite.”

– The spirit of Zheng He

Conclusion – The Admiral Who Sailed Beyond Time

Zheng He’s voyages were not just journeys across seas — they were acts of imagination.

He proved that oceans are not barriers, but bridges, and that humanity’s greatness lies not in conquest, but in connection.

His life reminds us that history is not written only by those who conquer — sometimes it is written by those who unite.

More than six centuries later, the world is still learning what Zheng He understood in his time:

The horizon is not the edge of the world — it is the beginning of understanding.